We’re just a few short days away from yet another Legend of Korra anniversary, which came to an end on December 19th, 2014. (Wait. Is three years long? Is it short? What the hell has time been doing lately?) With its sequel comic Turf Wars released over the summer, and its second chapter due at the end of January, Legend of Korra has enjoyed a bit of a reawakening. …Unless you’re a Fandomental, in which case we never shut up about it in the first place.

However, perhaps related to this, 2017 also brought a fresh wave of criticism. Do a quick YouTube search and you’ll find plenty: “Animated Atrocities”, “The Problem With The Legend of Korra”, “Legend of Korra is Garbage and Here’s Why”, “Avatar: The Last Airbender Vs The Legend Of Korra | Here’s The Problem With Korra”…all released within the last year, just to name a few.

I’ve watched a few of them, and and their core, it seems pretty indicative of how we discuss media now anyway. It’s that RedLetterMedia formula, where you can hyperfocus on flaws and present them in an entertaining matter. Which believe me, is something I’m no stranger to. I’m also the last person to say how someone should react to a piece of media, even if I can be confused by it. I may find something pandering that others love and feel validated by; at the same time, all the validation I got out of ‘Korrasami’ is something often bemoaned as half-assed representation. It’s all fine though, because for all we talk about Watsonian vs. Doylist lenses, it’s the third lens that matters the most in fandom experience: reader (or viewer) response.

That’s something I kept reminding myself after trying to get through a third one of these videos, which less than two minutes in asserted:

“[Legend of Korra] spends most of its time playing ‘remember this??’ to the previous show, and never really develops an identity on its own.” —Lily Peet in “Legend of Korra is Garbage and Here’s Why”

Well, I disagree! And I disagree on a level that is deeply felt, because of how long I’ve spent thinking about the identity of The Legend of Korra (LoK) versus its predecessor Avatar: The Last Airbender (ATLA). So my options are to sit and be annoyed for 90 minutes, possibly making my own lengthy reaction based on my own lengthy takeaways from the show, or to just…explain why it is that I think LoK is all that and a bag of chips. Because oddly enough, even though we’ve extolled various aspects of the show (while lovingly bemoaning others), we’ve never made the Definitive Case™ in its favor.

So without an ounce of hyperbole, here’s why LoK is the greatest show to have ever graced our TV screens (and ultimately online apps), and if you disagree you’re objectively wrong and beyond saving.

A Foundation in Transgression

LoK is a sequel series. I know this is likely obvious to anyone who’d click on this article, but I feel that it needs stating, because it’s important to understand that its roots are in the same philosophy as ATLA. It is quite literally its spiritual successor, as Korra is Aang’s. And like any decent sequel, it is thematically linked.

ATLA centered on the concept of balance, authenticity, and self-betterment. It was done with the backdrop of an imperialist war, the cycle of abuse, and genocide (for kids!), but it was the character growth that made it so compelling. Zuko’s wonderfully nonlinear redemption arc is considered one of the best out there, which is especially due to the fact that his primary antagonist was…himself. He had to grapple with the concepts of strength, justice, and duty, until he finally realized that it was his empathetic connections and concern for others that should be his sources of motivation. He chose to break the cycle of abuse, though even “taking down” his secondary abuser (Azula) was not framed as a fist-pumping moment, but a sad and poignant reality.

At the same time we’ve got Aang, who was on a more “traditional” hero’s journey. Yet I use those quotes because while he was the reluctant hero who lost a mentor, had a rather literal “death and rebirth” [abyss] at the mid-point, a very literal ‘refusal to call’ just before the events of the series, and the acceptance of his role in his own terms at the climax, he was an 11-year-old pacifistic survivor of genocide whose solution was disarmament, which flew in the face of 10,000 years of spiritual guidance. It wasn’t executed perfectly, and there were aspects to Aang’s scripting that felt a tad clichéd, but it’s hard to view ATLA, or Aang, as being particularly formulaic.

This isn’t touching the excellent supporting cast who had their own growth throughout the series.

Then came Korra. LoK, too, grappled with the same themes as ATLA, with balance being fully explicated as the theme of the final season, though just as pervasive throughout. There’s a rather insidious misconception that LoK is “the opposite of ATLA”, when it’s not at all. The conclusions about humanity and the inspiring messages are more or less completely identical. Hell, even Aang’s and Korra’s arcs were both about settling into their role as Avatar and defining what that meant to them. It was just from completely different angles.

This is where the transgressive nature of LoK comes in. The series wasn’t designed to be “the opposite” of ATLA, but co-creators Bryan Konietzko and Michael Dante DiMartino (Bryke) challenged themselves to create a protagonist who was the “opposite” of Aang. What would would happen if instead of a reluctant hero, we had an overeager one? If instead of a male pacifistic monk with a strong spiritual connection, we had a female ‘snowboarding’ kid, whose comfort-level was with immediate, physical action?

Now, that doesn’t mean Korra and Aang are complete opposites, since they both have a gregarious side, a staunch commitment to justice, an optimism about human nature that at times plays out as naivéty, and readily empathize with those around them—even if Korra felt that wasn’t a skill she could fully apply until the end of the series. (Which makes sense in the context of her healing, but is less born out of evidence where she’s quite obviously concerned for her fellow man from the get-go.) They’re not opposite people, or opposite personalities, but opposites in their willingness to be the protagonist.

Also, Bryke insisted that they would not write another travelogue.

It was a fascinating experiment, because we know what the arc is for the reluctant hero. We’ve seen it in Harry Potter or Lord of the Rings or even Shrek, and it’s even unfolding with Rey before our eyes in Star Wars.

This is no knock against the hero’s monomyth, and certainly not against Aang’s story. There’s a reason we find it exciting today, just like the Odyssey fandom probably swept over Anatolia at the end of the 8th Century BCE. Also, like I detailed above, Aang’s story was refreshing on its own merits. It’s just that we know what it’s going to look like: the world needs the ‘chosen one’, and the hero ultimately takes up this mantle, embraces their duty, and defeats/solves whatever injustice/trial they face.

So…what do you do for a character that already wants to be the chosen one. Hell, a character that fully embraces and takes pride from this role by the age of 3? I know “I’m the Avatar and you gotta deal with it!” is about as divisive a line as they come, but that’s the whole essence of this. Because how do you push a character like that towards growth? You make a world that doesn’t want her. You take the idea of a “chosen one” and have society reject it. You take all of her eagerness, her bravery, her physical prowess, and you set her against an enemy she can’t punch: her own irrelevance.

ATLA tells us that Aang can be the hero needed by the system if he capitalizes on the opportunity and “steps-up.” Korra is told to step down. An indigenous, brown, bisexual woman was put in this situation, and isn’t that just so damn fitting?

I’m not saying if you’re marginalized in any way and didn’t latch onto Korra’s journey, then you’re watching the show wrong or should feel bad for missing this. What I am saying, however, is that the restraining forces in Korra’s life are ones that are quite identifiable to many of us who have been marginalized by society, and for that reason, there’s a heavy personal validation surrounding Korra’s character. Again, what’s validating for me doesn’t have to be validating for you, but it’s kind of rude to dismiss this aspect of the show, or bemoan Korra as a character archetype.

Because here’s the thing about that archetype: how do you win against a system in which you don’t quite fit? What victory is there that’s possible?

You blow the damn thing up.

Korra’s arc wasn’t stepping into a role she was hesitant to fill. It was willing the change she wanted to be into existence. I’m talking very literally: she physically ripped open a new spiritual age. You think Aang went against the grain by talking to some Lion Turtles, how about undoing the entire legacy of the first Avatar and the subsequent 10,000 years?

Which, of course, she solidified in the series finale, in the cultural hub of the world.

When I call LoK “transgressive”, I’m not just trying to say it’s interesting or even unique. I’m saying that the very fiber of the show upended structures as we know it, both in the Avatar-verse, and outside, where Bryke and their writing team was pushed outside their comfort levels. Korra screamed for her right to exist, while also discovering and defining what that existence meant to her, and what she needed.

It was really just…authentically queer, and I mean that in a post-structuralist academic sense that isn’t relegated to her final handhold with Asami. (Though what a perfect thematic endcap, when you think about it.)

Writing Workshop

I’m not sure I can overstate how much I love that Bryke were really pushed and tested when writing Korra. And I know that making this claim sounds really pompous too: “Silly writers! It’s clear you didn’t understand your own character at first!” Worse still for my ~DEFINITIVE~ piece here, this isn’t something that can be objectively proven. It’s completely a matter of opinion how well someone thinks a character is scripted, or if the plot enhances their journey.

Here’s what I will say though, and if you find this compelling, it really does shine a different light on the show and Korra’s arc: ATLA was a very, very well-planned program. We can quibble about “filler” episodes (Bryke didn’t actually want seasons that long), and even fall down rabbit holes about scrapped fourth seasons that um…skeptics of the final few moments are fond of, but really the timeline and Aang’s mastery of the elements were presented in a clear way with [mostly] great pacing. Same with Zuko’s arc and when he joined the Gaang. I’m less compelled by aspects of Book 3 (Footloose?!), but this was a tight show that delivered a finale matched to the stakes of the series, with an emotional culmination for both the protagonist and deuteragonist that made sense in the context of their journeys.

LoK is not that. Books 3 and 4 feel the most planned and certainly the most well-executed in terms of pacing and cohesion. But even there, you can see aspects of the final season that didn’t quite come together and choices in focus that I doubt would have withstood a robust drafting process. (It’s important to note that they had budget slashes and were playing scheduling musical chairs during this time.)

Book 1 was originally written as a mini-series, though the episodes that aired were finalized knowing there’d be three more seasons following. It does feel a little *neat* at the end, like a self-contained unit. And unfortunately, like a self-contained unit that wrapped up just ‘cause. Its messaging was plain wonky—punching your enemies eventually works?—and though Korra went through a considerable trauma during its events, the ending amounted more or less to “magic powers fixed my depression.” It works *fine*, but going back through the season, there’s just not much to it, and nothing that’s particularly thematically linked to the rest of the series. Even the theme of “balance” was undercut since the antagonist’s downfall was met with a shrug, only for us to find out that it sparked off-screen political reform once the next season began. Good to know!

Book 2 is more or less a dumpster fire, where the tensions introduced in the first half were almost completely scrapped so that we could have cataclysmic stakes in the second. Don’t get me wrong: I see a TON of potential in exploring the tensions between the Northern and Southern Water Tribes. Instead, we got a bizarre rendition of Hamlet with hand-waved politics, Korra being told she started a war for some reason, and Mako the Super Cop being the only character with half a brain. Then, almost randomly, we were shown “Beginnings”, where the first Avatar separated the spirit and human worlds after defeating the ultimate evil spirit during an event called Harmonic Convergence. Wouldn’t you know it, but it was due to come again in just a few weeks!

Now, the ending of Book 2 was perhaps one of the most exhilarating possible, since that was when Korra did said creation-of-her-own-reality and became the first Avatar of a new spiritual age. It’s amazing what a good ol’ cataclysm can do for a narrative. But whatever someone’s opinion is of this show, there’s not a soul who can argue this was a well-planned and tightly executed season. I find it fascinating to analyze, since it more or less deconstructed its entire core and paradigm. Yet as an art form, it was a hot mess.

Even Korra’s decision to leave the portals open wasn’t well-explicated, though given that it followed her tapping into her inner spiritual strength in absence of any “Avatar” (Raava) presence to defeat the manifestation of chaos and despair, you could say that she was just going with her gut that she was finally willing to trust a bit.

But of course, this was just halfway through the series. Book 3 centered on the world struggling to adapt to Korra’s decision, ending with Korra going through a [third] major trauma. In some ways it’s weird that she trusts her instinct and pays for it, but her antagonist was acting out of the nature of her inherent role as Avatar—the thing she and the world were still in the process of defining. By Book 4, her confidence was shaken, she didn’t feel able to be the world’s Avatar, and she also needed to physically and mentally heal. Meanwhile, the world keenly felt her absence and needed specifically her. When she “returned,” it was doubting her old instincts, until she learned to lean into uncertainty and find a balanced perspective for herself, and her antagonists.

She won her ultimate battle by finding commonality with her antagonist and talking to her from a place of immense vulnerability and strength.

Now, Bryke have asserted that Korra’s spiritual journey was planned from the beginning, but do I think any of these details were part of that? Not at all! In fact, her spiritual journey in some ways culminated in Book 2, with Books 3 and 4 being her leaning into those implications and growing to a place where she would confront the world’s problems not out of insecurity or bravado, but from trust in herself and the spiritual world she created. And like I said, it was really not until the second half of Book 2 that anything was even vaguely thematically connected both to LoK’s endpoint as well as the central messaging of ATLA.

So what happened? Again, it’s nothing that can be proven, but it’s something deeply felt: Bryke learned to listen to Korra. They let go of a bit of control, and saw that Korra’s story—the one of finding her place in the world and blowing up systems to bring it about—needed to be told. Oh and she was also falling in love with her best friend along the way, but that’s not so much a focal point as it was chemistry that they leaned into. If only we were so lucky elsewhere.

If I can be rather flowery, Bryke’s own growth as writers paralleled Korra’s journey too. Though rather than creating a new spiritual age, they nagged Nickelodeon executives so that they could push the boundaries on LGBT representation further than it ever had gone before in Y7 programming. Because that was how badly they wanted Korra’s full story to be told; it was how badly she needed her place in the world.

There’s something perceptible, yet ineffable about this dynamic that you can feel when watching LoK. For me, it’s exhilarating since it is more or less the unabashed assertion of agency for this indigenous, mentally ill, bisexual female protagonist. Where do we get this anywhere else? Seriously? For others, I suspect it’s frustrating in its sloppiness, and feels uneven. Hell, for me it’s frustrating in its sloppiness and feels uneven. But it’s the authenticity and the absolutely, unabashed “I am here” mentality that has kept me engaged…

After All These Years

Forgive that transition—I couldn’t help myself. Yet I will say, over a thousand days have passed since LoK ended, and it’s still relevant. I suspect, unfortunately, it will be a long time before what I just described is either common-place, or no longer needed due to broader systemic justice. Hell, even Korrasami is going to remain the progressive gold-standard in queer representation for some time while TV is stuck in a paper-thin Closer to Earth mode, and movies think Josh Gad winking at the camera is sufficient.

But in general, this is a show that will age well. Speculative fiction has that advantage, since there’s nothing immediately dating it, and the theme of “find inner peace and balance” is something that’s always going to be relevant. At worst, Meelo’s jokes will be supremely not funny, but they’re mostly there already, and no one in-verse takes him seriously anyway.

Even more, I’m finding a shocking political relevance in Book 4, despite Bryke politics being…well…

Book 4 though. You know, where there was a totalitarian leader who targeted immigrants and chucked them into labor camps under the guise of security, while regional elected officials tried to resist her takeover, and those who put her in power stuck their heads in the sand about how disturbing things really were because they thought they’d be able to take care of her and get her to step down before it got too bad. Call it hyperbolic if you want, but the Izumi-Merkel parallels write themselves with her Hundred Year War guilt. Even Wu’s completel political inefficacy has some relevance, with him being more or less a puppet the establishment (Raiko + Tenzin) was controlling (appointed a team of ministers for him).

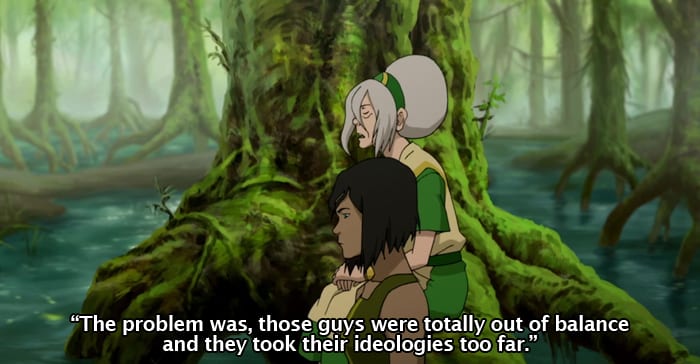

Nothing is one-to-one here, though there’s useful messaging in all of it. Especially Toph’s comments about how at their core, Korra’s former antagonists were fighting for some cause worth examining, but they fell horribly out of balance. It’s that open-mindedness and consideration that really does have to be our path forward, no matter what the situation. I mean, fight the fascist hiding in the giant robot lady who’s shooting a laser everywhere. But also, it behooves us to understand our foes, and most importantly, ourselves.

Out of the Destruction Love Did Bloom

LoK is a meaningful show, and as I just described, a relevant one. It’s a show I personally relate to, and I find interesting as a journey in and out-of-verse.

Does that mean that these criticism videos are disproven? Of course not. Because to be frank, I could easily fill 90 minutes with complaints and nitpicks about aspects of the material. What was the purpose of Lin’s heroic sacrifice if it was immediately undercut and her trauma was never addressed? How was a democracy established in six months? Why were we given essentially the same plotline with Varrick and Wu in the final season at the expense of screentime from our main cast of characters? And for the love of god, how did Asami just up and leave Future Industries during the events of Book 3??

This is just what immediately sprang to my mind, but it’s not like there aren’t plenty of missed opportunities, cringe-worthy moments (Meelo’s farts come to mind, though I know the target audience is probably quite happy with that), places where the world-building is a bit lacking (particularly on a political level), or even just places where the themes or character moments aren’t serviced well. I happen to think just about every piece of media has flaws, and I also believe that 90 minutes could be produced on ATLA in the same vein. Because it’s pretty easy to hone in on one problem, speak passionately about why it’s a problem, and convince a lot of people it is a problem. How else could someone have made an hour and a half video on it?

But to decree that LoK is bad since it has flaws and probably could have used another couple of drafts (because Nickelodeon was being so munificent already) in my opinion, suggests that there isn’t a serious attempt being made to engage with its messaging, what it is people do find compelling, or what the character journeys were. Unlike certain shows, this isn’t one where that engagement will come up empty. Hell, even focusing on B-plots, like Tenzin’s shedding of childhood idealization and his navigation of fatherhood himself, shows a certain significance and thoughtfulness woven into the fiber.

LoK isn’t even a Lost, where character arcs might be compelling, but the worldbuilding was so lazy (by design) that it rendered the entire experience moot. You can nitpick about metalbending logistics, or argue that “Beginnings” retcons ATLA’s portrayal of the lion turtles, sure, but the core of the show is sound. And you certainly don’t have to accept an incredibly flawed principle at the onset, like a theme park where robots were programmed to experience pain for…reasons…

I think finding and analyzing the flaws in LoK is actually one of the most rewarding parts, interestingly enough. Because part of it involves guessing where Bryke began to find their way and seeing how that affects things like character voice, and the other part involves trying to solve the most complicated political or economic problems that they accidentally set-up. How did Asami leave Future Industries during Book 3? Well, you and I will have to sit down and discuss the state of international trade following Harmonic Convergence before we can get into her corporate strategy.

LoK is like a multi-layered puzzle. The more you look for meaning, the more you find. The more you set out to solve, the more it gives you a question. From what I can tell, the critical group sees this too. It’s just that I find it worth fixing, because I found its central message and character journey refreshing, compelling, and validating. They didn’t. We don’t have to argue it; I just want you to see why it is that my crops are thriving, and I’m hoping you find a way to share in the bounty. Because I have too many damn zucchinis again.