Point: The finale of Lost is a storytelling failure. It’s emotionally overwrought, filled with heavily-saturated flashbacks, wooden dialogue, and double-digits minutes of tearful staring. It’s a cop-out ending, a sudden insistence that character arcs trumped all, despite six seasons of building its brand on cliffhangers and last-second reveals. It’s a narrative betrayal.

Counterpoint: The finale of Lost is messy, faltering, and brilliant. It is the only possible capstone to a show that obsessed upon the dangers and the necessity of ascribing meaning to the world, a perfect non-answer to show that had been skeptical about answers from the start. It is a brave, inspired, and compassionate narrative leap.

It’s been just over seven years. As Damon Lindelof’s more recent show will tell you, seventh anniversaries come with lots of baggage (or, maybe they don’t). In any case. Let’s talk about Lost.

A Question of Interpretation

Every season of Lost ends with an epistemological crisis. The survivors of Oceanic Flight 815 (and friends) clash over the proper interpretation of a sign, and what to do about it. In the end, without any real answer, they blow the sign up.

- In “Exodus,” the survivors see black smoke on the horizon, and Danielle informs that the Others are on their way to kill them (they’re not) because they want to steal baby Aaron (they don’t). They blow up the door to the Hatch, which Locke is convinced contains the secret of the Island and Hurley is convinced will only bring trouble. The Others – the ostensible reason for all the action in the finale – were somewhere else entirely, and end the season by kidnapping Walt (WAAAAALLLLLLLTTT) off a raft.

- In “Live Together, Die Alone,” (the best episode of Lost) the question of meaning falls on the countdown clock in the Swan Station. Locke, who had been the biggest proponent of the ritual entering of the numbers, has turned on it, insisting that it’s nothing but a cruel, meaningless trick (no zealot like a convert, no atheist like an ex-true-believer). His refusal to enter the numbers results in Desmond using a key to blow the hatch up, but not before they come to a more central realization. Several weeks earlier, when Locke had been pounding on the hatch door in a fit of despair and demanding a sign, Desmond turned a light on. It was a coincidence. Locke read it as the Island giving him a gift (it wasn’t) and Desmond read it as a gift of hope provided for him while he was contemplating suicide (it wasn’t). More on that in a bit.

- In “Through the Looking Glass,” the symbol in question is the freighter parked just offshore of the Island. Having been told it’s a rescue mission orchestrated by Desmond’s girlfriend Penny, the survivors spend the entire finale, and risk multiple lives, to get in contact with it. It is not, in fact, Penny’s boat. And even if it were, and they had been rescued – in the episode’s closing flash-forward Jack is sporting a full-on Sadness Beard (all the better to store his dwindling supply of pain pills), wailing at Kate that they have to go back.

[The survivors, showing uncharacteristic restraint, manage to not blow up the freighter until the end of season four. They blowup an underwater communication station instead (sorry Charlie)] - In “There’s No Place Like Home” the question at hand is the Island itself. One group of survivors, led by Jack, attempt to finally make it off the Island. Another, led by Locke and Ben, are attempting to protect it. At the center is a question of what the Island is and means to these people. In the episode’s flash-fowards, we get to see a reversal: Jack is attempting to lead a group back to the Island; Locke is off-island and dead. The survivors then go off book, and rather than blowing up the Island they displace it in space and time (L O S T).

- In “The Incident” the symbols veer towards the more literal end of the spectrum as Jack argues with fellow castaways about whether to detonate the core of a hydrogen bomb at the drilling site that will one day become the Swan Station. He believes his actions were return them all to the present day. Others think (understandably) that it will just blow them up. The other symbol of the episode is Jacob who is presented as both a guiding figure and as a distant, uncaring puppet master. He doesn’t blow up, but Ben does his Ben thing and stabs him to death.

Of course, this isn’t necessarily news. You could say the same of nearly every mystery novel, movie, or show. There’s not enough information, and it’s the characters’ job to discern the clues. Sometimes they are not very good at it.

But from the start, Lost has been less fascinated by the questions themselves, and more fascinated by the misattribution of meaning. It cared about its mysteries to a certain extent, but was always more intrigued by how people tried to grapple with them. People are wrong all the time. They’re wrong passionately, dangerously, selfishly. Lost is a show about surviving (or not) in a world where questions don’t have answers.

Jeremy Bentham, with the Jesus Stick, in the Nondenominational Worship Center

People liked to make fun of Lost for its sloppy, haphazard system of references. There would be constant close-ups of character’s books, weird pastiches of religious writings on walls, and an embarrassment of characters named after philosophers. This is usually chalked up to superficiality or laziness – that the writers wanted to get credit for name-checking deep ideas, but didn’t want to put the work into integrating them into a cohere, compete narrative system.

That’s fair. But sometimes messiness is intentional. The characters on Lost started as archetypes. Not that they were archetypes, necessarily. But they saw themselves as such. Jack was the doctor with a god complex, Sawyer was the con man. Sun was the oppressed wife, Charlie was the druggie rocker, Kate was the damaged grifter. Michael was the absent father, Sayid was the torturer. And on and on. None of them were simply these things, but it was how they saw themselves.

Coming to the Island put cracks into all those facades. And it slowly started to change them, like a prism refracting them into something new. Lost is a show about people questioning their assumptions about themselves. All well and good. But it’s real genius comes with what comes after: it explores the perils inherent in building yourself up into something different. If you weren’t who you thought you were, what then can you be? If you were wrong, or if you failed the first time, what’s to prevent you from doing the same thing again? Recreating yourself is terrifying. Belief is necessary, but it’s so dangerous.

The books and names and references, then, weren’t clues. They were possible paths, each with pitfalls of their own.

What Am I Supposed to Do?

In this light, Lost isn’t a mystery show. It’s an anti-mystery show. Clues don’t lead to illumination, more information only worsens the muddle. Narratives constructed on clues exist precariously, until they come tumbling down again.

Nearly every character on Lost was constantly trying to navigate a world filled with potential belief systems. Charlie tried to transition from heroin addict to protective father figure. But his insistence on control often only damaged his relationship with Claire. Sayid tried to redefine himself and put aside his past as a soldier and torturer. But he often built his new identity on the precipice of the old one, so with the slightest of nudges he’d tumble back towards his old self. Michael’s decision to commit fully to fatherhood was lovely, but also gave him a myopia that led him to murder two people and betray his friends. You could write an essay on any of the characters on the show. But for now let’s focus on two: Locke and Ben.

John Locke was saddled with an almost comedically awful backstory. He was an orphan, he was bullied as a teenager, was conned out of a kidney by his birth father (who later pushed him out a window and paralyzed him). This left him bitter but determined: unlike other characters John was in the midst of rewriting his own story before he ever arrived on the Island. The crash of Oceanic 815, and his newly-regained ability to walk, simply provided him with the template.

More than any other character, John was willing to fling himself head-first into new narratives. He was desperate for one. And in a lot of ways, it did his character a lot of good. John was immediately imbued with a new confidence, and he acted as mentor figure for struggling younger characters like Charlie, Boone, Walt, and Claire. He crafted a new narrative for himself: that he had been brought to this place for a purpose. And that the Island was a special place that needed his protection.

Of course, this being Lost, dedication to a single narrative comes with a price. John attacked Sayid to prevent him from using a makeshift radio. Bolstered in his mission by the discovery of the hatch, he proceeded to drug Boone and then put him in a position that led to his death. The discovery of the Swan Station only amplified this tendency. John’s single-minded dedication to pressing the button every 108 minutes shaped his narrative over the course of season two.

Until it didn’t: once he stopped believing in the Island’s power he refused to push it, or let anyone else push it at all. And it continues in Season 3 and beyond: a short span of episodes he steals dynamite, blows up a Dharma station, attempts to murder a prisoner, and blows up a submarine that could have taken his friends off the Island. When they almost get off anyways, he murders a woman he’s barely met. John was a believer, swinging back and forth between opposing poles of certainty (and often plowing through anyone in his path).

All of this occurs, of course, because John is easily manipulated – his desperate need for the Island and himself to be imbued with meaning makes him an easy target. But it also occurs because of John’s single-minded determination to make the world fit with his chosen picture of it. He thinks his belief will lead to understanding; it leads to his death in in motel room. Belief saved John; it also destroyed him.

What About Me?

The same could be said for Ben. Ben is Locke in reverse: both born premature, both gifted with single-minded dedication to a cause, both told they were special until they weren’t. But where Locke was desperately seeking purpose until he found it on the Island, Ben was given purpose early on, until the Island took it away. Ben is Lost’s textbook case of the dangers of constructing a narrative around yourself. He had far more information than Locke did, but it didn’t save him.

Ben was one of Lost’s most compelling characters because he most effectively played with the rules of the show. Ben lies – it’s what he does. And in lying, he effectively feeds into or upends the narratives of others. He enables Locke’s desire for purpose when he needs him to blow up a submarine. He digs up Sayid’s history of violence when he needs help in his battle against Charles Widmore. And he manipulates Jack’s guilt and uncertainty to get back to the Island. And this becomes doubly interesting because Ben plays around with tactical lies to maintain his own inviolable narrative: that he was chosen by Jacob to protect the Island.

He clung to the narrative at desperately as Locke ever did. But there was one key difference: Ben’s “specialness” was always more codependent than Locke’s. While the latter saw his relationship as directly with the Island, Ben’s was always mediated through the distant, unseen power of Jacob. Where John was a prophet, Ben was a terrifyingly committed lieutenant. And unlike John, when his narrative was falling apart, Ben got the chance to finally question Jacob to his face. It’s an outlet of seasons’ worth of barely-contained anger, as Ben asks why he had never received the acknowledgement that he thought he ought to be allotted. He spouts a list of grievances, complaints about how his story has not played out as it should. And it culminates in a question: what about me? Jacob doesn’t confirm or deny. He doesn’t say that Ben’s work has been meaningful, or that it’s been meaningless. He simply responds with a question: What about you?

There’s an undercurrent of cruelty to it, a flippancy that makes Jacob feel aloof and unappealing. But it’s the only possible answer. Ben wanted validation, for his ultimate authority to give him the comfort that what he was doing was right, that the story he had chosen to craft was correct. He doesn’t get it. No one gets it on Lost. It’s impossible. Jacob simply tells him that it’s something that he must decide for himself. And that brings us to season six.

Live Alone, Die Together

If Ben’s non-answer marks one philosophical pillar of Lost, the season two finale “Live Together, Die Alone” marks the other. Locke has entered one of his phases of belligerent doubting, insisting that the button – which he had dutifully pressed for weeks – was a scam. Desmond, who knew a lot about dutiful button-pressing, was with him. The question at the center of the season was rather simple: what happens if you don’t enter the numbers and push the button? But another issue arose as the two men waited for the clock to run down. Weeks ago, before the hatch had opened up, Locke had pounded on its door, demanding answers and validation in the wake of Boone’s death. Inside the hatch, Desmond was about to kill himself.

Both characters had their own narratives that were in the process of unspooling. When the light turned on in the window of the hatch, they both suddenly and definitively altered. It was entirely coincidental: there was no intrinsic, definitive meaning behind the event. It just happened. They saved each other by accident. And it offered an early glimpse into the things that can happen on Lost when instead of attempting to shape your own narrative, and bulldoze others in the process, you let it quietly fall into place like puzzle pieces that fit with the people surrounding you.

A single, coherent answer to what the Island was, why everyone was there, and what they ought to do would have negated the entire premise of Lost. That was the point: there aren’t answers – or there are partial answers, unsatisfying answers – and you have to move ahead anyways. And that’s why there’s beauty at the center of the finale and the sixth season, despite a lot of messiness in execution. The point of the season was that each character let go of the narratives they were clinging to, or the swirl of possible choices they could make, and simply decided to write a new story together. So much of Lost was characters demanding answers, demanding explanations that they would never receive. It ended with the characters simply creating one.

I understand why people don’t like the last season. Really, I do. But I’d also argue that it’s an absolutely fitting ending to the show, pertinent to the themes and concerns expressed from the very start. Lost was a show that balanced the necessity and peril of belief. It created narratives simply to undermine them, and to watch how characters would respond. It empathized deeply with the individual need to craft a narrative for oneself, but also refused to deny the dangers that were implicit – especially when done alone.

The flash-sideways of the last season were sometimes clunky or poorly-executed. But the idea that lay behind them was rather lovely, and a perfect capstone to Lost. You’ll never get the answers that you want. Insisting upon them is brave, but will so often hurt you and those around you. Learn what you can, listen, and work with those around you to create the world you want to see. It wasn’t perfectly done. But it was different, it was meaningful, and it was a bravely sentimental concept to see on TV.

Lost was wildly flawed. It has some truly awful episodes, and some truly awful plotlines. Damon Lindelof & Carlton Cuse clearly still had some work to do on how they crafted female characters. But it was also such an earnest, vibrant show, so different in its conceptualization and concerns than nearly anything else that has ever been on TV. I’m so glad it existed. The final season, and the finale, were an integral part of the world it was building, and the message it was trying to convey. It was the only way to finish such a sparkling, imaginative, and compassionate mess of a show.

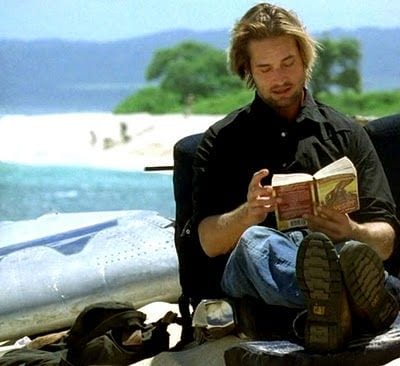

Images courtesy of ABC