“Many Partings” is a nice chapter, if not a necessary one. It’s a chapter-long farewell between our characters (and their world) and puts a continued emphasis on the themes of irrevocable change and lingering hurt. It drags by traditional narrative standards. There are four distinct scenes of gift-giving (six if you are willing to count the Forest of Druadan and, uh, Éowyn as gifts). Nearly every scene is structured the same: our dwindling company comes upon an old, familiar setting, meets an old, familiar character, there’s talk of changing ages, and then there’s a bittersweet farewell. So I can understand criticism of this chapter. But it’s also just… nice? Comforting. The Lord of the Rings is such a melancholy story at its core that it’s nice to give the narrative a moment to simply dwell in it, to walk through the world before we move into the end game.

The World is Changing

Loss is central to Tolkien’s story. He’s writing about the ending of an age, and all the good and bad that entails. It’s been present throughout the story as something impending; now it is something that is happening, and everyone is talking about it. “You know the power of that thing which is now destroyed,” Arwen says. “And all that was done by that power is now passing away.” “The New Age begins,” says Gandalf to Treebeard. “And in this age it may well prove that the Kingdoms of Men shall outlast you, Fangorn my friend.” Treebeard himself picks up the motif when talking to Galadriel. “It is sad that we should only meet thus at the ending. For the world is changing. I feel it in the water. I feel it in the earth, and I smell it in the air.”

This sense is underlined throughout the chapter also by the fact that time really is moving faster. For most of The Tower Towers and The Return of the King, each chapter covered a few days (at most). Since the downfall of Sauron, however, time has sped up drastically, with each chapter often covering months. This hits a high point in “Many Partings,” in which covers about two and a half months and often has the feel of a high-speed rewind of the of the Fellowship’s long journey. They move from Minas Tirith to Meduseld to Helm’s Deep, from Isengard to Dunland, past Lórien and on to Rivendell, all in the span of a few pages.

The large funerary party drops off bit by bit, people pealing off to new futures, until it’s just Gandalf and the hobbits, heading towards the Shire. It’s fitting that this happens in an autumnal context. The company arrives in Rivendell as September comes in “with golden days and silver nights.” They depart when Frodo “looked out of his window and saw that there had been a frost in the night, and the cobwebs were like white nets.”

My favorite moment in all of this sense of loss actually comes from a quiet moment during the journey, when Tolkien mentions how long Galadriel and Celeborn lingered, wishing to speak with Gandalf and Elrond.

Often long after the hobbits were wrapped in sleep they would sit together under the stars, recalling the ages that were gone and all their joys and labors in the world, or holding council, concerning the days to come. If any wanderer had chanced to pass, little would he have seen or heard, and it would have seemed to him only that he saw grey figures, carved in stone, memorials of forgotten things now lost in unpeopled lands.

On one level this verges on goofy—Tolkien reveals a line or two later that this is largely because they are just staring each other down and communicating telepathically. But on another level, it’s such a nice resonance with The Fellowship of the Ring, and all the times the Company came across old statues or broken-down masonry, some forgotten remnant of older ages.

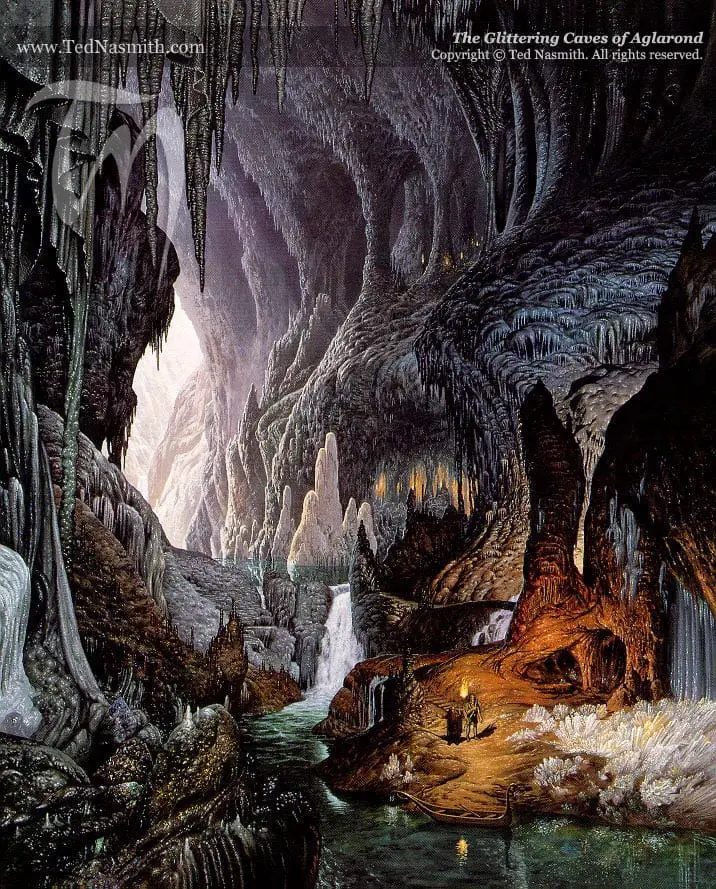

It’s worth noting that this period of transition—which so easily could have been a scene of tension and bitterness—really focuses on growth and understanding. Éomer and Gimli resolve their death pact over the most beautiful lady in the world (insert quiet eye-roll here) by agreeing that it’s fine that one prefers the Morning and one the Evening (insert another here if you’d like). Legolas and Gimli take each other to their own home turfs, the Glittering Caves behind Helm’s Deep and Fangorn Forest. Isengard goes from a sharp, industrial hellscape to a “garden filled with orchards and trees.” It works as a nice continuation of Tolkien’s tendency to balance loss with new starts.

You Have Doomed Yourselves, and You Know It

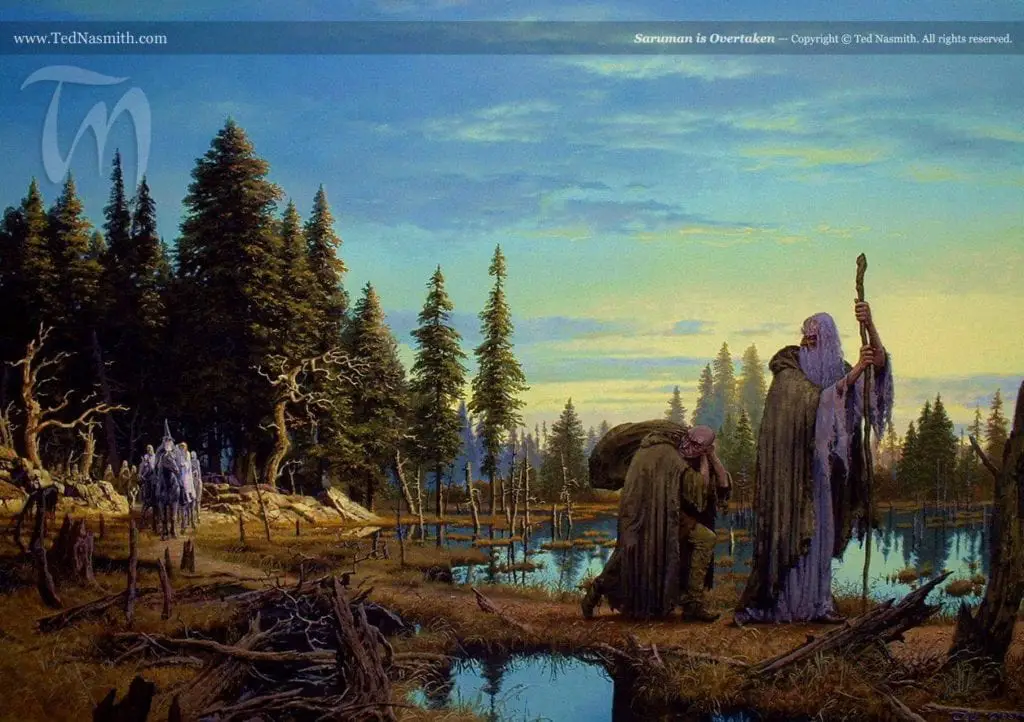

My favorite scene in the chapter, though, is the encounter with Saruman. Saruman is probably Tolkien’s closest analogue to Denethor: insecure and imperfect, “evil” only through failings rather than any kind of innate moral perversion. Tolkien is good at writing these two, especially their dialogue, and their anger and desperation gives them an immediacy that some of Tolkien’s other characters lack. They are more certain in their opinions than any of our heroes, which makes them both more dangerous and more appealing.

Saruman has little to lose at this point in the story, but he still holds on tenaciously to his pride. He’s remarkably petty in this chapter, nearly all of his lines amounting to vindictive little snipes. Gandalf mentions that Aragorn would have shown him wisdom and mercy had he waited at Orthanc. “Then it is all the more reason to have left sooner,” Saruman replies, “for I desire neither of them.” Galadriel offers him a last chance to come back to them, to work for rehabilitation. “If it truly be the last, I am glad,” said Saruman; “for I shall be spared the trouble of refusing it again.” He mockingly asks the hobbits to give him some pipe weed. When obliged, he steals Merry’s pouch, presumably just to max out his petulance.

But there’s also clearly a layer to him that still thinks he’s won—solely because those who disempowered him so thoroughly are being slowly, quietly, dethroned as well.

“Go! I did not spend long study on these matters for naught. You have doomed yourselves, and you know it. And I will afford me some comfort as I wander to think that you pulled down your own house when you destroyed mine. And now, what ship will bear you back across so wide a sea?” he mocked. “It will be a grey ship, and full of ghosts.” He laughed, but his voice was cracked and hideous.

It’s a nasty little diatribe, ending with a mocking recitation of Galadriel’s own poetry back at her. Laughter, which Gandalf had used to finally overcome Saruman and his voice, has been twisted and broken into something hurtful rather than healing. It’s no wonder he heads off to the Shire, attempting to destroy the one group present that he perceives isn’t already being killed off by time itself.

Final Comments

- I am excited to get back a bit closer to the hobbits. We have a lot of foreshadowing of Frodo’s fate (…or, people just saying it outright). But we don’t yet have much internal sense of him until quite near the end.

- I was intrigued to see that the Isengard area was renamed the “Treegarth of Orthanc.” I wasn’t familiar with garth, but it’s apparently a Middle-English word meaning “a piece of enclosed ground.” I want it to be related to garter but apparently it is not. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ It is, however, related to yard and all those Norse mythological gards (Midgard, Asgard, all that, Anglicized from the Old Norse garðr). After all what is the world what one big enclosed ground.

- Less fun to me was Tolkien’s use of trothplighted, which essentially means stateofbetrotheled (plight+troth). Calm down, Tolkien.

- It’s a small moment, but I quite like that Aragorn and Éowyn get a last conversation. It feels nice and authentic, a hint of wistfulness but both parties wishing each other the world.

- Aragorn mentions renewed hope in the search for the Entwives, as “lands will lie open to you eastward that have long been closed.” Treebeard though, is… less than excited by the option, simply shaking his head and saying it is too far to go. I know what Tolkien is going for here, but it also makes me laugh.

- It’s a small bit I may be reading too much into, but I do like how Aragorn seems to be subtly on a different page than the Third Age oldies around him. Treebeard calls him out on making a promise with the timeline of “forever.” More interestingly, Aragorn attempts to give Frodo a free pass through all of Gondor and whatever he wants to take, a decidedly forward-looking, Fourth Age gift. Arwen, in her only line of dialogue, reads the situation astutely enough to offer Frodo her boat ticket out.

- It was a little jarring to come across Treebeard’s words to Galadriel: “It is sad that we should only meet thus at the ending. For the world is changing. I feel it in the water. I feel it in the earth, and I smell it in the air. I do not think we shall meet again.” It’s the only line of dialogue that I feel has been really subsumed by the film, to the extent that it feels odd to read it in print.

- Treebeard’s reasoning for letting Saruman go was interesting to me—he released him as soon as he deemed him to be no threat, as caging living beings seemed inherently wrong to him. “You should know that above all I hate the caging of living things, and I will not keep even such creatures as these caged beyond great need. A snake without fangs may crawl where he will.” I’m curious about whether or not it’s fair to correlate this opinion with Tolkien’s own. I want to say yes, but Gandalf also mentions that Treebeard may have been manipulated into it, and the events of the next few chapters complicates matters.

- Old, post-Ring Bilbo is both sweet and sad. “‘Well, if you must go, you must,’ he said. ‘I am sorry. I shall miss you. It is nice just to know you are about the place. But I am getting very sleepy.’ Then he gave Frodo his mithril-coat and Sting, forgetting he had already done so.”

- Prose Prize: Then the Riders of the King’s House upon white horses rode round about the barrow and sang together a song of Théoden Thengel’s son that Gléowine his minstrel made, and he made no other song after. The slow voices of the Riders stirred the hearts even of those who did not know the speech of that people; but the words of the song brought a light to the eyes of the folk of the Mark as they heard again afar the thunder of the hooves of the North and the voice of Eorl crying above the battle upon the Field of Celebrant; and the tale of the kings rolled on, and the horn of Helm was loud in the mountains, until the Darkness came and King Théoden arose and rode through the Shadow to the fire, and died in splendor, even as the Sun, returning beyond hope, gleamed upon Mindolluin in the morning. I enjoyed the chance to stop in on Rohan one more time. I think it’s still Tolkien’s most interesting and stirring setting and culture.

- Next Time: We go back to Bree (and I think maybe to the edges of the Shire?) and trouble’s afoot. See you in a few weeks!