Massive spoilers for Until Dawn, Undertale and Die Hard, particularly the fate of each stories villain.

Hans Gruber is cooler than John McClane. The Joker is cooler than Batman. Darth Vader is cooler than Luke Skywalker. The villain is often the coolest character in any given plot. This is known.

But being cool is not the same thing as being relatable. As much as we might enjoy watching Gruber’s master-plan unfold, we still cheer when he falls off Nakatomi Tower. As much fun as we got from the chief antagonist, we never actually rooted for him. Instead we root for the heroic protagonist. This is ordinarily how stories are supposed to function.

Yet that is not always the case. A video game by nature tells a longer story than most other mediums (with novels being an exception). It is simple arithmetic that determines we must spend more time getting to know a villain in a ten hour video game than during a two hour movie. The result is that in a well-written video game the antagonists are usually more fleshed out than an audience is traditionally accustomed.

In these cases something strange can happen; the player can start to relate to the villain far more than the hero. Using Until Dawn and Undertale as my examples, I intend to take a look at this issue and pose one simple question. Is it a flaw or virtue of the story when the audience starts to love the villain?

Ten Hours Until Dawn

Long plot recaps will not be necessary for this examination of villains. The heavily abridged version of events in Until Dawn is that a year after a horrible tragedy, a group of eight college kids go back to the isolated mountain ski lodge where said tragedy occurred. They find themselves stalked by numerous dangers and must survive until dawn.

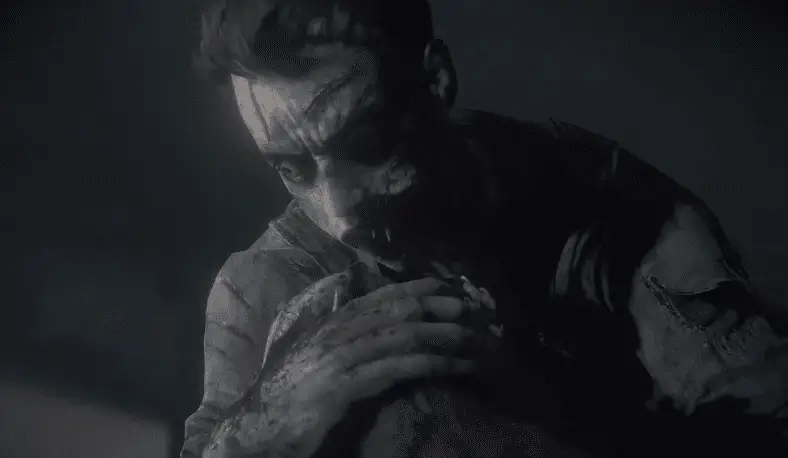

One of these kids is Josh Washington (Rami Malek). Josh is clearly invested in the plot far more than most, being both the older brother of the twin sisters who died the year previous and a member of the family who owns the ski lodge. He invites the same people back to the same place on the anniversary of his sisters’ disappearance, despite the tragedy being instigated by a cruel prank played on one of the sisters by most of the group.

When people start being stalked, kidnapped, haunted, psychologically tortured and (possibly) killed, Josh very quickly becomes suspect number one. Even Josh apparently being cut in half by a saw blade a few hours in is not enough to dissuade most players that he is responsible for everything. Sure enough, with four hours left until dawn it is revealed that Josh is the man that has been dressed as a psycho and tormenting his friends all night.

So, open and shut, clear cut case, right? Josh is an antagonist who while somewhat sympathetic in his motivations has wildly overreacted and become a monster. He is not irredeemable by any means, but he is clearly a bad guy.

Or he would be, if that is where the plot ended.

Without a Choice

Time for one my patented lists, displaying the series of unfortunate events that have led Josh to pretending to be a serial killer to torment his friends. (I am heavily cribbing off of this Game Theory video, so kudos and thanks to MatPat).

- Josh was diagnosed with depression at the age of nine. He is twenty during the game’s events.

- He has been bounced around between at least four psychiatrists and prescribed numerous different drugs.

- None of these drugs work, leading Josh to attempt both overmedicating on them and stopping taking them completely.

- Why don’t the drugs work? Probably because Josh shows none of the symptoms of depression, but displays every symptom of schizophrenia over the course of the game.

- Meaning thanks to a miss-diagnoses his schizophrenia has gone untreated for ELEVEN.

- Not to mention that the drugs he has been prescribed are providing large amounts of brain chemicals that he does not have any deficiency in already.

- While he is passed out drunk one night, his twin sisters disappear and are never seen again.

- Soon afterwards he attempts suicide.

- All throughout this is father is becoming more and more distant.

- He begins suffering intense hallucinations of his sisters who ask him why he let them die.

Do you feel differently about Josh now? Is it slightly hard to hate the guy knowing his back-story? Does a part of you not wish you could just give the guy a hug? It gets worse.

It is possible, depending on your choices, for any and all of the eight kids to die during the game, and it is also possible for any and all of the kids to survive. However, there is a catch, as only seven of them are capable of living their lives again after the events. Josh only has two possible outcomes; either he dies horribly (his head literally explodes) or he is turned into a literal hideous monster. (Yes this game has supernatural elements. It’s the best).

In a game about choice, Josh is doomed no matter what.

First as Tragedy

So a twenty year-old kid with a serious untreated mental illness is beset by family tragedy and ultimately suffers a horrific fate. It would take a staggering lack of empathy not to feel sorry for Josh. That said, he did still torment and endanger is friends (though he did not kill any of them, that was the monsters), and he is still a villain. Why then do I care more about him than anyone else?

This may partially have something to do with Rami Malek. The star of Mr. Robot is in another stratosphere of talent compared to the rest of the cast. He is one of the finest actors of his generation and it is no shock that he sells his character far better than the rest of the cast.

Another factor might be the complete breakdown he suffers in the game’s closing stages. Or the fact that almost every character (except Jessica) is capable of killing, attempting to kill or deliberately endangering their friends, and he is not. Or that should he be killed, it is his mutated sister who kills him.

Yet what it really comes down to is his lack of control. He could not choose to not develop a mental illness. He had no opportunity to save his sisters. Josh is doomed from the very second the plot kicks into gear and there is no action he can take to save himself. His life is a tragedy. He may have turned to villainous actions, but his fated damnation makes it easy to look passed that. Josh Washington is a classically tragic character doomed by fate, and for that reason I care more about him than seven random college kids.

Kill or be Killed

One of Josh’s saving graces is that he never tries to kill anyone. Could I end up rooting for a villain who does? How about a villain who kills everyone who has ever lived and steals their souls? It is time to talk about Undertale.

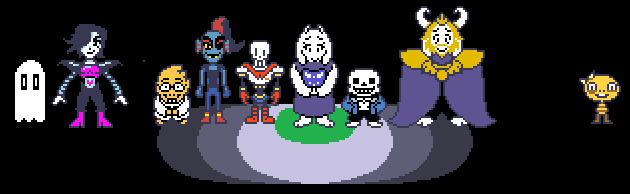

A kid falls into an underground world filled with monsters. Shenanigans ensue. A skeleton fails to make spaghetti. Another succeeds in making bad puns. A fish bench presses children. A robot hosts a cooking show. Everything is impossibly charming and wonderful. Then a flower tries to kill the world.

The flower seeks to destroy as a way of avoiding boredom. He lacks a soul, and is thus unable to feel empathy (or, indeed, anything at all). He is cruel, sadistic and utterly without mercy. How could anyone possible love this horrible creature?

On his first attempt to destroy the world he fails due to some souls he had hijacked rebelling against him. On his second attempt he succeeds in absorbing the souls of every monster in the world and literally becoming a god. Finally he has enough power to turn back into his original form.

A cute little kid named Asriel.

Your Best Friend

Asriel died many years previous and his ashes were sprinkled on a flower. When that flower is granted sentience due to some highly irresponsible science, it retains his memories but not his ability to feel. This poor kid is trapped in a hellish existence and is lashing out wildly.

As the final fight against Asriel draws to a close, he becomes more and more childlike in his demeanour. His words are not those of an evil villain trying to destroy reality, but of a scared little kid, from his reason for not killing the main character:

“You’re the only one that understands me.

You’re the only one who’s any fun to play with anymore.”

To his desperate loneliness:

“I’m not ready for this to end, I’m not ready for you to leave.

I’m not ready to say goodbye to someone like you again…”

To the part where he throws a temper tantrum and shoots you with a beam of hyper-death.

“So, please… STOP doing this…

AND JUST LET ME WIN!!!”

To the final confession of what is motivating him.

“I’m so alone. I’m so afraid.”

Finally he bursts into tears, apologises for everything he did and frees the monsters from the underground. Everyone gets a happy ending, with the exception of Asriel, who is doomed to become a soulless flower once more and forever.

And that is how you make people care about a villain who committed genocide on a global scale.

Intentions and Villain Conventions

With the context now explained, we can turn back to the question at hand. Is it a problem that Josh Washington and Asriel Dreemur are the two people I care about most in their narratives when they also function as villains?

Intention of an author is not something that can ever be readily dismissed. To my mind there is a worthy distinction to be made between someone with noble intentions who ends up portraying a negative stereotype and someone who deliberately portrays a negative stereotype out of malice. Yes, both actions are bad, but bad in different ways and to different degrees.

Basically, it does bare thinking about whether or not the creators intended Josh and Asriel to provoke sympathy. The question of Asriel is an easy one to answer. It is very clear from every context that surrounds Asriel (the emotional swell of music during his boss fight, the image of a crying child, the tone of the rest of the game) that he is supposed to spark empathy in the player.

Josh is a much more tricky case. On the one hand, the writer’s primary goal was to create an antagonist in a slasher story and that genre is frequently guilty of using mental illness as an unfortunate crutch. On the other, the idea that they would choose to have Josh be diagnosed with depression and subsequently fail on every level to illustrate him experiencing its symptoms (while hitting every single symptom of schizophrenia) is a little hard to swallow.

Occam’s razor suggests Josh is supposed to provoke sympathy, particularly in the game’s closing stages. Accepting this, the question changes; why would the creators buck narrative conventions and make the villains the most sympathetic characters?

What Kind of Story Are We Telling?

It would be a failure on the part of the writers if we ended up empathizing most with the people standing in the way of the heroes goals. It would be poor story-telling if the sight of Hans Gruber falling to his doom provoked sniffles rather than cheers. If the story functions on the assumption that the hero triumphs by killing the villain, then we should want to hate the villain, not love them.

However, all stories need not follow this structure and the world would be a poorer place if they did. Shaking up narrative convention should be encouraged, as should the subversion of standard troupes, provided the result still forms a cohesive structure. We need not always hate the villain.

In fact, perhaps it is even a worthy cause to help us empathize with those who do harm. In our divided world it is important for us to at least try to understand what motivates those operating in opposition to our goals. How else can we fix a problem if we do not first understand it?

I realize this has gotten very high and mighty for an article with an inordinately nerdy subject matter and the original point is starting to get a little elusive. The question was whether or not it is a flaw or a virtue of a story that someone might end up loving a villain. My conclusion is that this love, like all love, must surely be a virtue.

It is no bad thing that I ended up caring more about designated villains Josh Washington and Asriel Dreemur than the heroes of their stories. In a medium filled to the brim with boring and grimdark space marines, it should be celebrated when a writer’s succeed in making me care at all. Or maybe it just says something about me that I frequently turn away from the morally upstanding heroes of fate, glance over at the clearly broken soul that is the villain and ask ‘What’s hurting them?’

Images courtesy of Supermassive Games and Toby Fox.