WARNING: Spoilers for Get Out (2017)

Near the end of Jordan Peele’s Get Out, when its protagonist Chris has nearly made it out of his predicament, as he is standing over the body of a white woman whose entire family tried to kill him and hijack his body, the police arrive.

In most horror films, the arrival of the police is a relief. When it came in Get Out, there was a collective gasp in the audience at my theater. Everyone held their breath. One viewer behind me muttered the F word.

That moment was deliberate. In fact, originally it wasn’t Rod inside the car, but the actual police:

“The movie was originally meant to be a more direct, brutal wake up call, to say guess what, [in] the horror movie with the black protagonist, the cops showing up at the end, that’s a different thing. […] What I love about the current ending, is that moment when the police show up, the audience does all the work of the original ending.” – Jordan Peele for THR’s Writers Roundtable.

The impact was such not just because we, the audience, instinctively knew black man + dead white woman + police does not bode well for our protagonist, but also because most of us had never seen something like that before on film.

END OF SPOILERS.

The reason it took so long for that to happen on film is simple: the structures of power in the film and television industry have kept it from happening.

I don’t mean “someone tried, and they didn’t let them”. I don’t know one way or another, anyway. What I mean is that the power players who get to decide what stories we see, who tells them, and often how they should be told, have remained predominantly white and male. They are the gatekeepers.

The word isn’t all that uncommon, but I first knew gatekeeping as a theory of Communication. Specifically “the process of controlling information as it moves through a gate or filter and it is associated with exercising different types of power.” (Barzilai-Nahon, 2011)

The gatekeeper is the person exercising this power. They decide what goes through, what ends up on our screens, our magazines, newspapers, and everything else.

It is not just one gatekeeper in any given situation. For me, it helps to think about it as a system. For example: imagine a media corporation was recently bought by a fast-food conglomerate.

A reporter discovers a case of massive food poisoning in the city, and spends time digging that story. When they get it to their editor, they will have to run it by their information chief, then it’ll go to the paper’s director, who’ll have to send it to their superiors at the corporate level, and so on until it gets to the fast-food conglomerate, who happens to own the restaurants where people got food poisoning.

“No, this story can’t be published, or it can be published but the restaurant’s name should not be mentioned.” If this system goes on for long enough, the editor will have preemptive answers to the stories their reporters bring to them.

Let’s imagine the reporter stays on, because they have a family and this is a good opportunity for their career, and maybe one day they’ll make editor. They’re a good reporter who believes in journalism, so they try. For years they try to get important stories through the gate, only to get rejected time and time again. They’ll start to pick their battles, and maybe eventually they realize there’s no winning. They stop trying. By the time they become editor, they will most likely uphold the system at their level.

Gatekeeping systems are often even more complex and storied than the one I’ve just described. As the film and television industries exist today, we can only imagine what that looks like. Scratch that, I think most of us imagine what that must look like.

Every year, media outlets and studio heads pedal the news that diversity is improving, that we’re making such strides for representation. Still, the gatekeeping system is in place, and its story is there for us all to see.

The Hays Code, a set of moral guidelines that restricted what could appear on screen, enforced from 1922 to 1968, is the most egregious example… but also, weirdly, the most transparent. It dictated things like how an LGBT+ character could only be presented on screen in a negative light, that no interracial couples were represented, or even how long a kiss could last on screen. Something like that is bound to leave remnants, and indeed the process of moving on from it has been long and painful, every change a fight.

Representation is improving on screen, yes. It has been since the end of the Hays Code, but it has been an uphill battle. Every change has been a struggle, sometimes one that must be had again for the same thing.

Five years ago studios were still upholding the idea that no one wanted a woman-led superhero film. Only three years the industry became widely aware of how harmful the Bury Your Gays trope was and is. But we’re moving forward, right? Yes and no. What’s happening behind the scenes sheds clearer light.

As of 2020, only 13.9 % of writers in Hollywood are POC, and 17.4 % are women. The numbers look promising in TV, with 49% of staff writers being POC, and 30% women showrunners, according to the WGAW. It may sound like a lot, but remember the complicated, multilayered structure of gatekeeping?

Staff writers can have very little power when it comes to storylines. They must pitch ideas to their first gatekeeper: the head writer or showrunner. Only 18% of showrunners are POC. And sadly, that is only the beginning of the system. How many POC writers do you think prefer to not pitch their bigger, bolder ideas, or get silenced? This is such a good opportunity, and one day maybe they may make showrunner, so they prefer not to disturb the waters. Sometimes, their showrunner is willing to support them, but they also have hoops to jump through, especially if working at a network. How many of those 30% women showrunners are WOC?

This is not to suggest that all of the people who are and have been in control are bad people with bad intentions. I don’t doubt most are well-meaning, decent people. A good portion probably don’t think about it one way or the other. That is the problem, though.

With mostly male and white gatekeepers historically, it is no surprise the representation of police has been overwhelmingly positive on film and TV for decades (with notable exceptions). LGBT+ people were unicorns, black women are stereotyped as always angry, Latinx as gangsters and cholas… They’re narrow worldviews that for a long time have perpetuated the comfort of the gatekeepers, who in turn are safeguarding the comfort of particular groups in business and society.

This is a reason why we are now seeing a phenomenon of requirement representation to get “woke points”, but it can often feel hollow and dishonest. It is to appease a part of society that has become more vocal, but done while still safeguarding the comfort of the same people in power. Things like adding LGBT+ characters to lure that audience in but then under-utilizing them or pushing them to the background. I don’t doubt a lot of them have good intentions, but that is simply not enough anymore.

There are so many varied and different experiences based on all kinds of things in this world; from the place you come from to the color of your skin to the school you went to. Yet our view of the world through media has been overwhelmingly filtered by very few of those experiences.

Recently, I watched a film called I’m No Longer Here (Fernando Frías) about a young man who is part of an extinct group that used to call themselves “Cholombianos” in Monterrey, Mexico. In many moments, the film made me uncomfortable. Its main character, Ulises, is a bullheaded teen who communicates little and refuses to let go of his life in Monterrey even when his life is threatened. It deals with cultural appropriation and identity and gang violence. It forced me to see a life so different than my own and urged me not to judge Ulises.

It makes us uncomfortable when we’re confronted with different perspectives, especially less privileged ones. The gatekeepers, as well as me, if I’m honest with myself, have grown comfortable and complacent with the narrow margin of the filters.

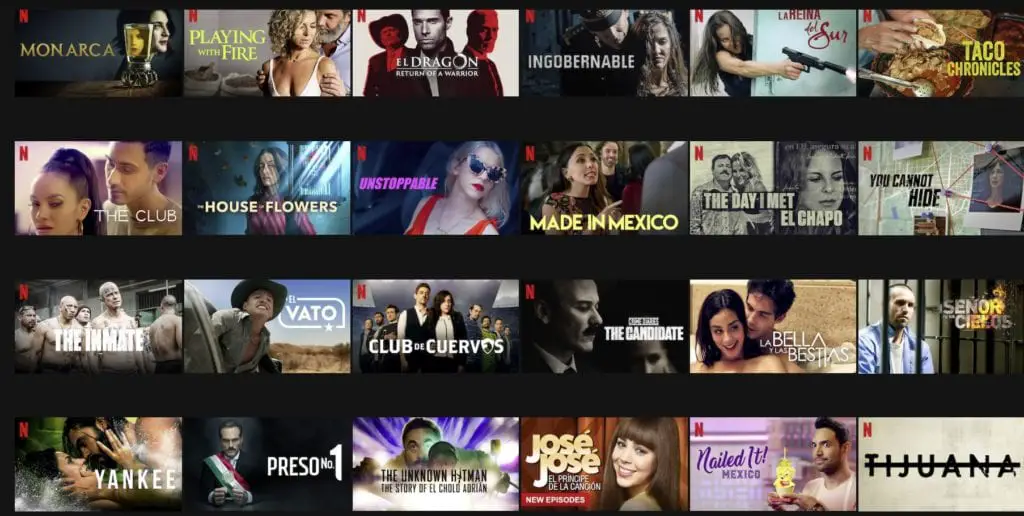

To be clear, I am not just talking about the US Industry here. My country of origin, Mexico, is guilty of putting mostly white, heterosexual people on screen. I’d even say it is more prevalent than in the US right now, especially on mainstream media. Look at the selection of Mexican titles for Netflix originals.

How many people do you see there who look like, say, Yalitza Aparicio?

It’s telling that Roma, one of the recent examples that could change the game in terms of mainstream representation, was written and directed by a white man. Alfonso Cuarón put great care in telling the story of his childhood nanny, and it has been widely praised. Still, the mere fact tells you a lot about where we’re at in Mexico.

The US Industry is what ours models itself after. The progress that the US has made has created direct and noticeable ripples in the Mexican industry. Mexicans consume a lot of US media, and the surge in diverse representation has created a direct echo in ours. That is not to put the crux of the problems in the Mexican industry fully on Hollywood. There is a lot we need to work on and ask for. I just want to illustrate a point of the importance of diversity in Hollywood beyond itself.

“Yes, you can have a trans character, but you can only have the one.”

“Yes, you can tell the story of this woman of color, but you must do it in a way that doesn’t truly challenge my position.”

“Yes, you may include this Black protagonist… but in a way that makes us look good for allowing you to tell it.”

The worst part is that it doesn’t even need to be said. At this stage of the game, no one has to utter the words—and I suspect almost no one does. It’s the status quo, it’s the assumed stance.

It is the reason Bryke never thought to ask if Korra and Asami could get together on Legend of Korra; the assumption was they couldn’t, as they wrote in the art book. How many more assumptions are there in writing rooms, in pitches, in meetings? It won’t change until the people in power change.

If there were more LGBT+ gatekeepers, friend groups wouldn’t consist of five straights and the one gay. LGBT+ people travel in packs! If there were more Latinx gatekeepers, characters would have the correct accents in Spanish way more often.

And it is very, very clear to me that if there were more Black gatekeepers, the representation of the police in film and TV wouldn’t have been the way it was for so long. Or at the very least it would be more balanced, and we’d have more examples like Get Out, Atlanta, and When They see Us.

Diversity on screen is very important. However at this point it’s even more important to have more diverse showrunners, executive producers, heads of department, and especially studio executives.

Now we know that for that, people in power need to make space. In some cases, they’d have to give their spot to someone else. More often than not, people who talk the talk aren’t willing to walk the walk. There will be resistance. The changes won’t feel honest on the part of those in power, because they won’t be. They’re very comfortable, and comfort is really hard to give up.

At this time emotions are running high. I have little influence and a very small voice in these matters, and this is more like an impassioned rant than anything else. Change will be painful and uncomfortable for many of us.

Progress is and will continue to be hindered if the industry continues to deny spaces of true power to diverse people. If the world… if we have to be dragged out of stagnancy kicking and screaming, so be it. It is high time.