Welcome back, everyone, as we dive into our last (!) book of The Lord of the Rings. It was always my favorite when I was little—whether because it functions as the emotional climax of the story I cared about or because it actually is the best book in the series remains up in the air. I’ve been awaiting moments like the charge of the Rohirrim, Eowyn’s encounter with the Witch King, Sam’s storming of Cirith Ungol, Minas Tirith, the Fields of Cormallen, and the Grey Havens, all with an odd mix of anticipation and dread. I love all of it, if I’m honest, but The Return of the King has always been special. The culmination and crystallization of all the story’s meaning and intent. I am hoping it holds up?

Gandalf and Pippin’s arrival at Minas Tirith kicks things off well. It’d be an easy place for a reader to suffer narrative whiplash. A group of orcs have captured Frodo, and Sam is on his own. Rather than get an answer, we swerve away towards Gandalf and Pippin, whom we haven’t seen in hundreds of pages. We meet some new characters, see some new places, but not much happens. But rather than try to fix this, “Minas Tirith” simply leans into it. It plunges the reader into a new world through the eyes of Pippin, who rushes into a Gondor that is brimming with the energy of imminent action.

Setting the Scene at Minas Tirith

Near the end of “Minas Tirith,” Pippin observes that for all the frenetic energy shown by Gandalf, and for all the ominous, distant fires of the signal beacons in the White Mountains, Minas Tirith feels still. His new friend, Beregond, has a simple explanation. “Everything is now ready,” he says. “It is the deep breath before the plunge.” It’s a good encapsulation of the chapter. There is a sense of looming, inevitable doom floating over the characters and their actions, but a parallel sense of stillness, of waiting.

Pippin is the perfect viewpoint character for this. In part, this is because of Pippin’s current emotional state. He is days away from being taunted by Sauron himself in the palantír and the weight of the encounter still hangs over him.

“This was the second, no the third night since he had looked in the Stone. And with that hideous memory he awoke fully, and shivered, and the noise of the wind became filled with menacing voices. A light kindled in the sky, a blaze of yellow fire behind dark barriers. Pippin cowered back, afraid for a moment, wondering into what dreadful country Gandalf was bearing him. He rubbed his eyes, and then he saw that it was the moon rising above the eastern shadows, now almost at the full.”

Pippin is jumpy and exhausted, ready to see flames in moonlight and hear menacing voices on the wind. And it’s a trend that continues throughout the chapter. In a moment of boldness he swears himself to Denethor’s service, only to later regret it and slip into loneliness. He is despairing at the sight of a Nazgúl in the distance, only to drag himself back upwards towards hope. Pippin’s very long first day in Minas Tirith is a buffets him all over the emotional map.

It doesn’t take long to see that Pippin’s mental state, besides being a genuine exploration of where he is on his journey, is also a microcosm. Minas Tirith is that same fear and jumpiness writ large. We can see it through the lighting of the beacons in the mountains, or through the last-minute rebuilding of the Rammas Echor walls surrounding the Pelennor Fields. Or, most particularly, through Beregond’s reluctance to even look towards Mordor, much less name it. These things could easily be rendered empty, or at least clichéd: a country preparing for war. But because we see them through the eyes of Pippin, processing his trauma and abruptly stripped of his best friend, they echo with a deeper resonance.

Pippin also serves as a good window onto the new world of Gondor. He’s the perfect mix of character traits: often ignorant, but always curious, friendly, and surprisingly perceptive. He knows almost nothing about Gondor, so we learn it with him. And while he knows next to nothing of the power players in the wars to come, he’s remarkably adept at reading their characters, giving us a window onto lofty distant figures whom we have yet to see up close. A good example is Gandalf, whom Pippin admits to knowing quite well and simultaneously not at all.

“He came and stood beside Pippin, putting his arm about the hobbit’s shoulders, and gazing out of the window. Pippin glanced in some wonder at the face now close beside his own, for the sound of that laugh had been gay and merry. Yet in the wizard’s face he saw at first only lines of care and sorrow; though as he looked more intently he perceived that under all there was a great joy: a fountain of mirth enough to set a kingdom laughing, were it to gush forth.”

It’s a wonderful moment for both Pippin and Gandalf. And it serves as a reminder, after a chapter of relative worry and inefficacy, how powerful Gandalf can be—and, simultaneously, that that power is rooted in the audacity of joyfulness in the face of despair.

But, perhaps even more than Gandalf, Pippin gives us a window onto Denethor.

Denethor

Guys! Guys. I cannot begin to tell you how excited I am to read about and talk about Denethor. His presence in the narrative adds so much texture and nuance to The Lord of the Rings. He is unquestionably a “good guy,” fighting to maintain the bulwark of Minas Tirith against the oncoming onslaught from Mordor. But he has a coldness about him and a streak of cruelty. He’s bright, but not bright enough. And he’s so proud.

In his first appearance, Denethor seems simply to serve as an indicator of the potential flaws and fallibility of Minas Tirith, and to act as a foil for Gandalf. His smile at Pippin is “a gleam of cold sun on a winter’s evening” compared to Gandalf’s fountain of mirth. Pippin himself declares a “likeness” between the two, “almost as if he saw a line of smoldering fire, drawn from eye to eye, that might suddenly burst into flame.” And for a moment, Denethor feels like the first real challenger that Gandalf has faced in a long time. He keeps him waiting. He makes no pretense of deference. And he declares that he has little interest in following Gandalf’s counsels.

But Denethor is clear-eyed: there’s no Wormtongue nearby on whom to cast the blame. And Pippin notices. Denethor “looked indeed looked much more like a great wizard than Gandalf did, more kingly, beautiful, and powerful; and older.” There’s something fascinating about watching someone parry with Gandalf, with no apparent deference or fear.

But while Denethor is being built up as a roadblock or threat to Gandalf, the threat is simultaneously diffused. Pippin, immediately after noticing that Denethor looked more powerful and kingly than Gandalf, discovers that it’s but a trick of appearances. And when Denethor actually lays out his platform, its brittleness and flimsiness in Tolkien’s moral universe becomes immediately apparent.

“You deal out such gifts according to your own designs. Yet the Lord of Gondor is not to be made the tool of other men’s purposes, however worthy. And to him there is no purpose higher in the world as it now stands than the good of Gondor; and the rule of Gondor, my lord, is mine and no other man’s, unless the king should come again.”

Gandalf will have none of it.

“I will say this: the rule of no realm is mine, neither of Gondor nor any other, great or small. But all worthy things that are in peril as the world now stands, those are my care. And for my part, I shall not wholly fail of my task, though Gondor should perish, if anything passes through this night that can still grow fair or bear fruit and flower again in days to come. For I am a steward. Did you not know?”

It’s a thorough and slightly venomous repudiation of Denethor’s platform, as well as a claim to a much broader jurisdiction of stewardship (there’s also a nonchalance towards Gondor’s fate that’s mostly for show). Gandalf is happy enough with it that he immediately turns on his heel and barges out. There’s a sense that Denethor is an annoyance to Gandalf. But not a threat. He’s simply a poor leader, fatally myopic in his scope.

All of this, of course, sets the stage for Aragorn. He’s the king destined to return to his throne, a prospect much more appealing if the person currently on it (or at the foot of it) can be questioned in his quality. Questioning Denethor paves the way towards our happy ending.

But that’s not all that it does. Because Tolkien makes an interesting choice here, and makes Denethor, Minas Tirith, and everything they touch more interesting and complex. Because Denethor never entered the story simply to serve as a foil for Gandalf or Aragorn or even Faramir. Denethor is here as a facet of Númenor. He’s our introduction to the problem of Gondor.

The Problem of Gondor

After Pippin’s interview with (interrogation by?) Denethor, Gandalf makes his own observation about the Steward of Gondor.

“He is not as other men of this time, Pippin, and whatever be his descent from father to son, by some chance the blood of Westernesse runs nearly true in him; as it does in his other son, Faramir, and yet did not in Boromir whom he loved best.”

On this re-read this is such an interesting choice to me. It’d have been quite easy to make Denethor a poor leader because he was not Númenorean. A figure who had fallen away from what had made them what they were. It would be a clean narrative. Denethor and Boromir, those without that blood of Westernesse, are flawed by their blinkered focus on Gondor and ultimately give in to temptation or despair. The true Númeroneans, Aragorn and Faramir, come in to take their place.

But it’s so much more interesting—more dynamic—that both Faramir and Denethor are “true” heirs of Númenor. They are simply different aspects of what it could be, depending on the choices that its people make. Denethor’s Gondor possesses the classic Tolkien flaw: an over-reliance on nostalgia and a static, white-knuckled grasp on the past. Faramir’s and Aragorn’s we’ll get to.

Just take a look at Pippin’s first impression of Minas Tirith as he rides in.

“Pippin gazed in growing wonder at the great stone city, vaster and more splendid than anything that he had dreamed of; greater and stronger than Isengard, and far more beautiful. Yet it was in truth falling year by year into decay; and already it lacked half the men that could have dwelt at ease there. In every street they passed some great house or court over whose doors and arched gates were carved many fair letters of strange and ancient shapes: name Pippin guessed of great men and kindreds that had once dwelt there; and yet now they were silent, and no footstep rang on their wide pavements, nor voice was heard in their halls.”

Minas Tirith is decorated by cold stone statues, tombs, and a desiccated tree. Tolkien compared the kingdom to “a kind of proud, venerable, but increasingly impotent Byzantium.” It’s an aging city, drying up as it clings to the things that once let it bear fruit.

And I think this matters very much as a message that introduces The Return of the King. It matters because it casts Aragorn’s arrival and Faramir’s trajectory in a light that’s less restoration and more re-formation. It matters because it highlights the whole series’ focus on the importance of moral choice, and fortitude in the face of fear. And it matters most importantly because, from the start, it introduces the persistence of change throughout The Return of the King, for good and for ill. It’s a story about the end of an age, and the pain and necessity of that. Tolkien himself has said it on the issue of time and change:

“Some reviewers have called the whole [series] simple-minded, just as a plain fight between Good and Evil, with all the good just good, and the bad just bad. Pardonable, perhaps (though at least Boromir has been overlooked) in people in a hurry, and with only a fragment to read, and, of course, without the earlier written but unpublished Elvish histories. But the Elves are not wholly good or in the right. Not so much because they had flirted with Sauron; as because with or without his assistance they were embalmers. They wanted to have their cake and to eat it: to live in the mortal Middle-earth because they had become fond of it (and perhaps because they there had the advantages of a superior caste), and so tried to stop its change and history, stop its growth, keep it as a pleasance, even largely a desert, where they could be artists—and they were overburdened with sadness and nostalgic regret. In their way the Men of Gondor were similar: a withering people whose only hallows were their tombs.”

It’s an opinion that’s contrary to many assumptions about Tolkien, though perfectly in line with his legendarium. And it’s a lovely theme to introduce The Return of the King. At its heart, this is a book about the end of an age—it is often brutally sad, and there is loss. But that does not eradicate the necessity of the change, or the new joy that can come with it. It echoes throughout the story, especially in its second half. I was surprised but happy to see it arise so early. We are off to a good start.

Final Points

- This was a particularly rich chapter, and one that had an immense number of things that could be talked about. I only picked a few. Please bring up more in the comments! Who’s a big Bergil fan that’s furious he didn’t make the cut? Who wants to chat about the character development evidenced by Pippin’s decision to check on Shadowfax before he went off to round two of breakfast? Is there anyone who can defend the aesthetics of Denethor’s hall over Théoden’s? (No.)

- I think that Tolkien’s message on dynamic and static societies here, writ large, also pushes against the idea of easy solutions. Aragorn’s coronation is a triumph, but I doubt Tolkien had any illusions that it was a permanent one. Gondor will not be suddenly rid of all its problems. It’s worth noting that Tolkien briefly flirted with the idea of writing a sequel to The Lord of the Rings focused on the kingdom of Gondor after Aragorn’s leadership. He later wrote it off as too depressing and flat.

- This is such a great chapter for Gandalf. He’s nice and dramatic towards the start, bursting into Gondor and announcing he has ridden in on the wings of war. He then declares that Minas Tirith as they know it is over, no matter the outcome. I enjoy that as soon as the reader meets Minas Tirith Gandalf yells that it will never be the same. Big fan of dramatic, portentous Gandalf.

- On a related note, I also like that people in Gondor give him backhanded compliments all chapter, cheering things like “Mithrandir, Mithrandir! Now we know that the storm is indeed nigh.” Ill news is an ill guest indeed.

- Another way in which Pippin functions as a good opening viewpoint character: he frequently thinks of Frodo. This is fitting, as Frodo is one of his closet friends and someone he loves and admires. It’s also a handy narrative tool as Tolkien switches threads. Pippin thinks about Frodo twice in this chapter, and Tolkien uses both occasions to mention where Frodo was on his journey, giving the reader who cares about that sort of thing a good indication of the story’s timeline. It also just serves as a nice mental link for the reader that makes the shift in narrative less jarring.

- I liked the ways in which Minas Tirith feels like a real city, as many cities in Middle-earth do not. The fact that Beregond directed Pippin to the Old Guesthouse in the lowest circle of the city, in the Rath Celerdain, the Lamprwright’s Street, is a useless narrative detail. But it adds a vibrant sense of reality to the city to know that there’s a quarter of lamp-makers. Very medieval.

- Beregond is such a good, charming guy! Sorry I forgot you existed, Beregond!

- I had forgot about this moment, and it was very charming. “Rumor declared that a Prince of the Halflings had come out of the North to offer allegiance to Gondor and five thousand swords. And some said that when the Riders came from Rohan each would bring behind him a halfling warrior, small maybe, but doughty.”

- Prose Prize: The dark world was rushing by and the wind sang loudly in his ears. He could see nothing but the wheeling stars, and away to his right vast shadows against the sky where the mountains of the south marched past. For a reason I can’t quite place I find Gandalf and Pippin’s breakneck ride to Minas Tirith to have a quasi-mystical air to it. It’s probably just because Pippin spends most of it on the edge between awake and asleep, atop an impossibly fast horse. But in any case, it has a really nice effect, opening the book one a strange and dreamy note.

- Contemporary to this chapter: SO MUCH. Because it happens so briefly, I forget that Gandalf and Pippin’s ride lasts for three to four days. In the meantime, Frodo & Co. move from the Black Gate into Ithilien, spend some time with Faramir and Henneth Annun, and sets out towards Minas Morgul. Aragorn, meanwhile, meets the Dúnedain heads out to Dunharrow, and travels the Paths of the Dead. Théoden sets out for Harrowdale, then Dunharrow. Honestly, Shadowfax, pick up the pace.

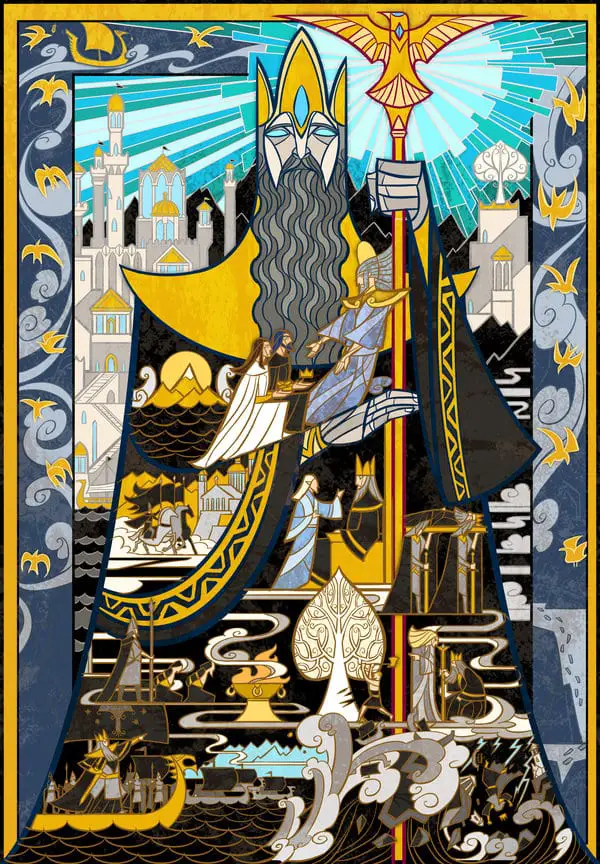

Artwork, in order of appearance, is courtesy of Ted Nasmith, Jian Guo, and aegeri.