Sometimes you’re just in the perfect mood for a particular type of movie. The stars align, the universe goes out of its way to ensure everything goes smoothly, and before you know it, you’re leaving the theater excitedly chatting with your wife and saying, “Well, that was a lovely movie.”

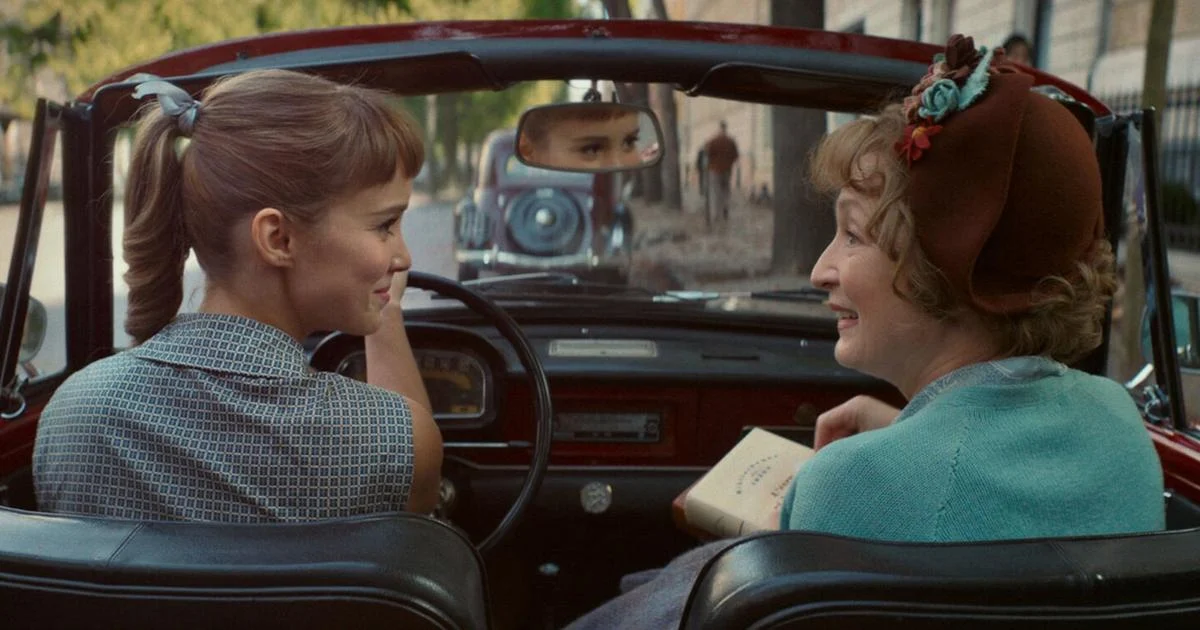

Anthony Fabian’s Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris could have easily been a trite and sentimental piece of treacle cinema. But it’s not. Fabian finds the perfect balance assuring all will turn out well for Mrs. Harris (Lesley Manville) but not without a few bumps in the road. It’s a neat little hat trick to pull off, and too many movies falter at the last minute.

But Fabian, who co-wrote the script along with Carroll Cartwright, Keith Thompson, and Olivia Hetreed, makes Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris a sublime pastry that dares to have more than cream filling. Fabian and his writers smuggle in class themes throughout the movie while slyly making Mrs. Harris a beacon of kindness and goodness without making her a pushover or a simpleton.

The success owes as much to Manville’s performance as Fabian’s direction and the script by committee, which, shockingly, doesn’t feel fractured or disjointed. Manville’s Ada Harris is a cleaning woman who lives life day to day, with a cheerful disposition and a welcoming smile. Manville plays Harris with quiet dignity and grace without ever playing her as a martyr.

Mrs. Harris is, as she opines to her best friend Vi (Ellen Thomas), “we are invisible.” A theme that runs deep and abiding throughout Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris. Just as the movie is about Ada finding love and happiness within herself and the capacity to dream, it is just as much about the world’s working class and how they are often ignored or made invisible—fitting then that our hero is herself an invisible woman and even more so that she is the one who loudly and proudly shines a light on the work done by the manual laborers.

Set in the 1950s, Ada has just discovered that her husband, missing in action these past few years is dead. Lost and adrift, she and Vi spend their days cleaning and their nights at the local pub or the dog track. Not until at one of her houses does she discover a gorgeous haute couture dress by Christian Dior. Learning that the dress costs 500 pounds, Ada goes about scrimping and saving to buy her dream dress.

Do not let the simple plot of Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris fool you. Fabian and his writers use Ada’s desire for the dress as a catapult. Fabian and his writers explore the myriad ways in which people do and don’t follow their dreams and how these decisions trickle down into the other areas of our lives. This is not some crass celebration of “consumerism” but a mediation on the power of dreams and how certain things represent ideas and hopes rather than mere material.

Soon Ada is off to Paris, having scrounged some money together through hard work and nifty luck. Upon arrival, she meets some well-meaning winos who welcome her to Paris and take her to the infamous Dior House. As they part ways, the jovial man tips his hat, “Remember, madame, in Paris, the working man is king.”

Time and time again, throughout Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris, Fabian provides obstructions and obstacles for Mrs. Harris but never in a manner that she can’t overcome them with some effort and the kindness of strangers. Mrs. Harris is not out to change the world, but she does change some people, and just as she changes them, they change her.

There’s the beautiful Natasha (Alba Baptista), a model and face of Dior who proves to be more than just a pretty face. She takes a liking to Mrs. Harris, as does the dashing accountant Andre (Lucas Bravo), who seems also to like the comely Natasha, a feeling she reciprocates. At least, when he’s not mansplaining philosophy to her. Ada also meets the dashing Marquis de Chassagne (Lambert Wilson), who gives the charming Archie (Jason Isaacs) a run for his money. Archie is always at the pub with a younger woman, but he always has time to flirt with Ada and visit her house to check up on her.

Of course, not everyone is a fan of Ada, such as the steely-eyed Claudine played to prickly perfection by Isabelle Huppert. But again, this is one of a dozen lovely little masterstrokes by Fabian and his fellow writers. There are no purely evil characters; aside from the occasional vindictive biddy, not everyone immediately takes to Ada. Nevertheless, the slight touch of melancholy realism gives Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris its genius.

Fabian takes all these characters and their desires and sews them together in a tapestry that looks at how we love the things we love and how these little things save us. Ada’s love for the dress is not just that the dress is pretty, but that she can see the stitching and tailoring of the ladies who made the dress. She recognizes it as the labor of love the dress so clearly is. “You’re not making dresses, you’re making moonlight.”

Ada gasps and coos as she’s allowed into the inner sanctum with the other older ladies and watches them sew with rapt admiration, even joining in herself. Meanwhile, poor Natasha, who yearns to study philosophy, is admired for her body and beauty. She is out on the town every night with a different man, representing Dior. These men celebrate her beauty, show her off, and treat her as a decoration, yet when she sees Mrs. Harris, she lights up and is relieved that she has someone to talk to.

Fabian and his writers do not shy away from some of the darker aspects of the fashion world. For example, they heavily imply that, although Natasha may not be having sex with these men, it is more than apparent that Dior is using Natasha’s body and sexuality as transactional elements. But, again, Ada sees the work underneath Natasha’s brain. She can see her desire to be seen as a whole person, not just someone who can wear a dress well because her measurements are the right sort.

Felix Wiedemann’s camera elegantly captures the essence of warmth and yearning in every frame. Scenes like Ada watching the Dior models parade in their dresses as she gazes awestruck at the beauty has an almost dreamlike framing to them. Wiedemann and Fabian slyly smuggle in a tale of self-discovery and romance into what appears to be, on the surface, mere froth. But Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris is deceptively shrewd. Not only in its dialogue, such as when Ada leads the Dior models and seamstresses on strike, while the aghast Claudine screams at the officer to do something. “I’m a communist, madam. I’m on her side.” Wiedemann makes scenes feel as if we have stepped into a painting one might see for sale on the sidewalks of Paris.

Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris is a big-hearted ode to anyone who has worked day and night to scrounge together enough money to get a little something for themselves. Fabian uses the character of Mrs. Harris, created by Paul Gallico and uses her to explore the holiness of the mundane, to find the joy in recognizing the smell of a flower because it reminds you of your husband and the heartbreak that often follows rash and foolish decisions.

Yes, Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris is predictable, but in many ways, it is not. Its forgone happy ending earns its sublime perfection by making us wonder if it’s ever coming. But in the end, it’s Manville’s Mrs. Harris, a woman who in many ways reminded me of my mother, who also cleaned houses and often never got the love and respect she deserved.

But I also saw myself, my wife, and my friends, anyone who has ever worked a job that left you so tired you could barely hold a conversation when you got home, will see a bit of themselves in Mrs. Harris. That’s the beauty and nobility of Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris. Of course, it’s all well and good to escape into blockbusters. But from time to time, it’s necessary to see someone who is more like us, or like our parents, and give us hope that we too can dream. And, if we’re lucky, even make a few of them come true.

Images courtesy of Focus Features

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!