Kamala Khan, the superhero known as Ms. Marvel, has a unique position in the comic book world. Not only is she an amazing character in her own right, but she’s also a thoughtful portrayal of people who are often underrepresented or poorly represented in fiction.

Ms. Marvel is a young teenage girl, she’s Pakistani-American, and she’s Muslim. All those identities and their points of intersection are a vital part of who she is and how she approaches the world around her, her personal struggles, and her status as a superhero. In short, Kamala is an opportunity for everyone to see a different type of character in the role of protagonist and superhero.

This representation is all the more important when we consider what’s happening in real life. If you’ve been following the news for the past year, you know we’re living in times of growing intolerance and xenophobia. In the real world, people like Kamala Khan are facing the effects of this bigotry in their lives every day. So what should comics do about this? Should they approach this issue at all? Should Ms. Marvel incorporate this climate in Kamala’s stories? If so, how?

The recent story arc of Ms. Marvel (2015) gives us some answers, exploring those themes both metaphorically and directly.

Being other

Before we proceed, I should clarify that I’m neither Muslim nor American. I can only speak from the limited position of an outsider, so feel welcome to add your own voices and experiences in the comments.

I do have some experience with being other, though. Here’s what I found: being other can mean a multitude of experiences, positive or negative, depending on what standard you’re being measured against.

Being other works great for me here in Brazil. I’m descended from Polish and Italian immigrants in a country that values ties to White Developed Countries™. I’m proud of my heritage, and I’m allowed to celebrate it. That sure doesn’t work for everyone—ask African-Brazilians or Haitian immigrants if their experiences have always been this peachy keen.

Outside of Brazil, being other is no longer a good deal for me. Turns out White Developed Countries™ aren’t as interested in us as we are in them, so I’m suddenly met with distrust. My appearance and my dual citizenship can shield me from most embarrassments, but I quickly learned that disclosing my nationality can lead to bad experiences.

Why am I telling you this? Because xenophobia is the fear, distrust, or hatred of what we perceive as foreign or strange, but not all foreigners are perceived the same way. That is especially noticeable in countries like the United States or Brazil, with populations composed of people from different backgrounds and heritages. Not every heritage, ethnicity, culture, or religion is treated the same, which in turn means not every other is otherized. The fact that some people have positive experiences with their otherness should not invalidate the struggles of those facing intolerance and bigotry.

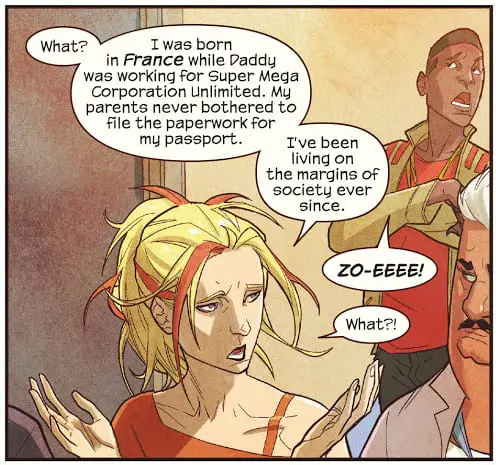

Also please don’t be this person:

Make Jersey City Great Again

The struggles of being different are a recurrent theme in Ms. Marvel stories, but they come back even stronger in the recent four-issue arc Mecca. Ranging from Ms. Marvel (2015) #19 to #22, the arc tackles xenophobia, racism, and intolerance both metaphorically and directly (if subtly).

In this story, we see the return of Chuck Worthy, an old foe with Hydra connections (and remember, Hydra means nazi). Ascending to power through not-so-legal means, Worthy becomes mayor of Jersey City and starts a campaign targeting super-powered people. What’s more, his minions Discord and Lockdown, as well as the newly-created agency K.I.N.D. (Keepers of Integration, Normalization, and Deference), brutally enforce his new laws.

Kamala is an obvious target, but her brother Aamir also becomes one due to an incident with superpowers a few years ago. As the city she was born and raised in and the city she has risked her life so many times to protect, Jersey City is an important part of Ms. Marvel’s identity. Now that city turns against her and her family.

It gets even trickier when Kamala finds out Discord’s secret identity: Josh, Zoe’s ex-boyfriend and a friend of Kamala’s since childhood (and a character that we have known since the very first volume of Ms. Marvel). Josh opens his heart to Kamala, and in turn, she reveals her own identity. Those discoveries impact both characters, and Josh lets the wounded Kamala run away, enabling her counteraction.

In the end, Kamala defeats the bad guys, Lockdown is arrested, and Discord escapes. Mayor Marchesi returns to her rightful position, while Chuck Worthy’s fate is left unclear. Everything is back to normal…more or less. As Kamala admits herself, this is not the kind of experience you’re likely to forget.

So what does this say about xenophobia and intolerance? Well…

Chuck them out

The main plot of the narrative serves easily as a metaphor for xenophobia, racism, Islamophobia, and intolerance in general. A significant portion of the population targets a group of people easy to identify as “different” and blames them for their problems. They ignore this group’s contributions and ties to their society, seeing threats where there aren’t any. There’s this sense that the targeted group doesn’t belong and isn’t welcome here, and the neighbor that chats with them about the weather is the same one that attends a rally demanding them to be arrested or deported.

The words coming from Chuck Worthy, Discord, and the K.I.N.D. agents are eerily similar to speeches we hear in real life:

[slide-anything id=”53512″]

Their methods and mentality are also not very different from stuff we’ve seen before too. The narrative approaches each antagonist differently, showing different takes on people seduced by this mindset.

People like Chuck Worthy, who prey on the fear or greed of others and offer them an easy target, are outright despised by the narrative and its heroes. Chuck is unquestionably a villain. So is Lockdown: willing to carry out even the most extreme orders, she doesn’t question her beliefs or regret her actions. These are the people defeated in the end.

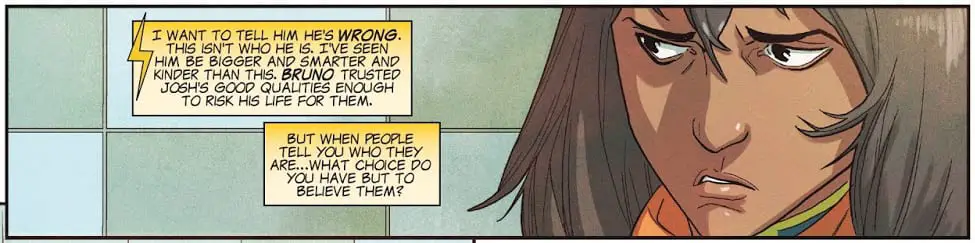

Discord, perhaps the most active antagonist during this arc, deserves more attention. From the beginning, there’s an attempt to humanize his actions and understand why he acts the way he does. In choosing a character we already know and are already invested in for the role of antagonist, the creators make us ask the same question Kamala does: how could he? It’s a question the book ultimately doesn’t answer, and I think that’s a wise choice.

The choice of Josh specifically is interesting. He’s the epitome of privilege, but he resents being told how lucky he is. That resentment pushes him down a path of extremism, but he never acknowledges that one thing doesn’t exclude the other. His problems and struggles are valid and not less real because he’s privileged, but being privileged shields him from a series of other potential problems and struggles that he actively inflicts on other people. Sadly the character doesn’t acknowledge this, which is probably more realistic but still frustrating.

It’s dangerous to humanize characters who perpetuate oppression and supremacism since it can easily enter unfortunate implications territory. This isn’t a “both sides are equally wrong” situation and treating as such risks absolving or condoning the inexcusable. An important choice in this regard was to have Discord still be treated as an antagonist in the end. Kamala acknowledges that she can’t give him a pass just because they were friends. As much as she thinks he’s better than that, that was the choice he made for his own life.

There’s also an effort in understanding what made crowds of people believe in and support Chuck Worthy. Ms. Marvel genuinely reevaluates her actions, trying to figure out if she legitimized this feeling in any way. In the end, she concludes that despite her mistakes Jersey City is still a lot safer with her around.

This is where the metaphor fails a bit, and it’s a common problem when you use a fictional group as a stand-in for real-life oppression. Superpowered people are an actual threat, even if not all of them. You have people like Kamala, who make the city a better place, but others still use their powers to endanger common citizens (as many comic book villains do). Fearing super-powered people is a reasonable thing in this context while fearing immigrants or Muslims is simply not. Similarly, Kamala admitting her responsibility makes sense for a superhero that occasionally destroys property, but it wouldn’t make sense for immigrants or Muslims who just want to live their lives.

Thankfully, the book still offers a more explicit stance against xenophobia and intolerance.

Divide and conquer

Muslim identity is an integral part of Ms. Marvel’s stories, and this one is no different. Several cultural references along the story contextualize Kamala’s faith, particularly her reflections on Eid Al-Adha, during which the events of this arc take place.

“It’s the kind of holiday that makes me take a big step back and remember all the things that are going right in my community. Everybody’s happy. Far away across the ocean, the pilgrims are returning home from Mecca. That’s the cool thing about Eid, I guess. In theory, it’s about sacrifice. Abraham’s sacrifice. Hajar’s sacrifice. But in the end, everybody lives. The only thing that actually gets sacrificed is a sheep. It’s like, if the good guys struggle long enough, they really can save everybody. Everybody lives. Every family is reunited. Nobody gets left behind.” (Kamala Khan in Ms. Marvel #19)

While Kamala has always struggled with feeling different, in the end, she has always been able to draw strength from her identities. She’s still proud of them and wouldn’t choose to be otherwise. We see that in the first issue of Ms. Marvel (2014) when she drops the possibility of looking blond and “beautiful” like Carol Danvers.

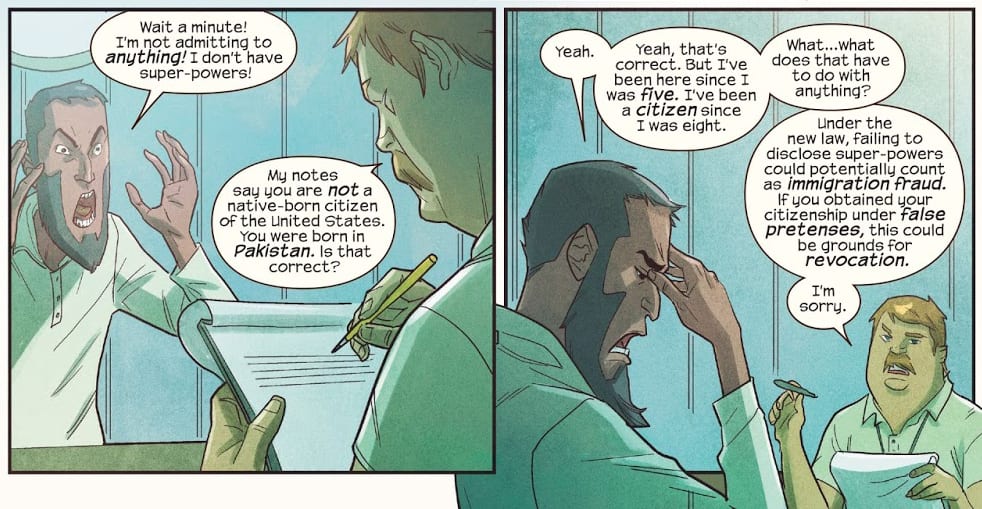

As the title indicates, this arc is very strongly Muslim. From the moments of happy celebrations with her family to the mosque becoming a shelter for those in need, Muslim identity is always presented in a positive light. Making Aamir a central character in this story increases this tone, not only because he’s always been proudly Muslim but also because through his experiences the arc becomes less metaphorical.

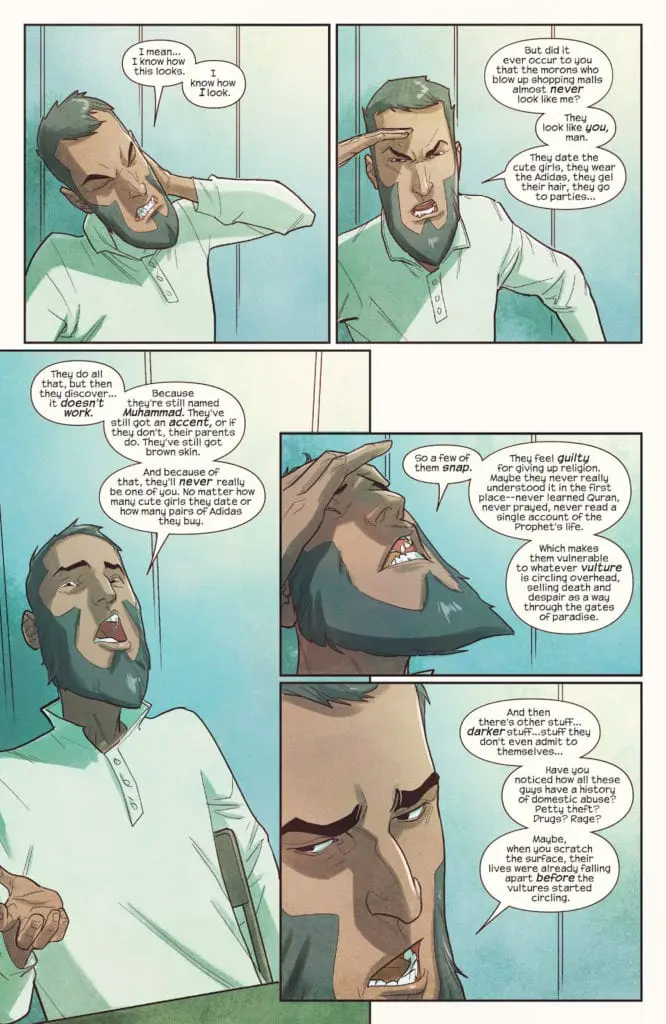

Aamir’s profiling and arrest, while connected to the main arc of targeting superpowered people, also explicitly show xenophobia, racism, and Islamophobia. For instance, when he’s being interrogated one of the reasons stated for his arrest is that he was carrying a pressure cooker, an object that could be used to make bombs.

During this interrogation, Aamir makes quite a long speech against Islamophobia and intolerance. Here’s an excerpt:

His status as an immigrant also comes up (unlike Kamala, he was born in Karachi and came to America as a child) and is used to threaten him:

The whole interrogation scene is a very politically charged moment, but how could it not be? Superpowers may be fictional, but being a Muslim or a Pakistani immigrant is not. You can’t ignore the consequences that Chuck Worthy or his methods would have in the lives of Kamala and her family. It wouldn’t be a realistic portrayal of those identities if it didn’t acknowledge the very real prejudices and biases they face.

Moments like this or the reactions of the fugitives when they enter the mosque are when the story leaves metaphor territory. They help reinforce the point the author is trying to make, just in case you think this is a story about fictional intolerance that in no way happens in real world.

And if you think that’s too political, well, I got some bad news about comic books for you…

Closing thoughts

As writer G. Willow Wilson says, one of the reasons Ms. Marvel is so successful is because readers are able to identify with her. The anxieties felt by young Muslims are also felt by several other people.

Stories have power, and it’s great that Ms. Marvel uses its power to address such relevant issues. It broadens the societal dialogue, even if just a bit, and hopefully empowers people who identify with Kamala and her family. And if you identify with Josh, hey, there’s a message there for you too.

The ending of the arc feels less fulfilling than it could have been. It’s easy to superpower your problems away, while in real life xenophobia or racism are not so easily solved. Still, the reflections Kamala offers on the subject very much apply to our real-world context.

The whole incident clearly changes Kamala and those involved, which goes to show that even if you survive difficult times, they’ll continue to impact you. Having your friends, neighbors, or home place otherize you and using your identity to hurt and dehumanize you is not the kind of experience you tend to forget.

As Kamala herself says,

“Most of the time, super-heroing means protecting the many from the evil of the few. But if there’s one thing the last couple of days have taught me… it’s that sometimes you’ve gotta protect the few from the collective evil of the many. Which, as it turns out, is much, much harder.” (Kamala Khan in Ms. Marvel #21)

True, but we still gotta try.