The last few chapters of The Lord of the Rings have felt a bit like a victory march. Since the unexpected triumph at Helm’s Deep, things proceeded along a consistently optimistic path. Everyone celebrated their success in “The Road to Isengard.” They reunited with old friends in “Flotsam and Jetsam.” And they confirmed their victory over Isengard in “The Voice of Saruman.” Things felt cheerful, and relatively relaxed: an unexpected dynamic for the close of a second act (after all, third-act dawns tend to look brighter thanks to the second-act darkness that comes before). Things seem calm. And then Pippin looks into the palantír.

The sudden shift in tone and momentum that results from this event shocks Book III out of its more lackadaisical pace and reorients the narrative. It’s an old trick – triggering a disaster (or near-disaster) just as soon as things seem safe and promising. But Tolkien utilizes it well here. Not only does Pippin’s encounter with the palantír inject the narrative with a shot of adrenaline, but it does so in a thematically coherent and satisfying way. It touches on the dangers and necessity of inquiry. It takes a look back to Saruman. And – maybe most importantly – it paves the way for Book IV, for Frodo and Sam.

The Palantír and Sauron

Pippin’s theft of the palantír and his experience with it happens quickly. The entire encounter with Sauron lasts perhaps half a paragraph. It’s an interesting storytelling choice: Tolkien dispenses with the possibilities inherent in playing out the drama of the encounter live, and instead lets what occurred slowly unspool itself to the reader.

To the reader, Pippin looks into the orb, sees some lights, and then something happens – he goes rigid, he cannot look away, he screams. It’s obvious that something is wrong. When Gandalf rushes up to him Pippin cries out in a “shrill and toneless voice” and shrinks back from Gandalf. “It is not for you Saruman,” he says. “I will send for it at once.”

When you know what’s happening, the impact of those words hits home immediately. But when you’re reading for the first time, the real import of what just happened only reveals itself as Pippin begins to tell the story of what happened:

I saw a dark sky, and tall battlements…And tiny stars. It seemed very far away and long ago, yet hard and clear. Then the stars went in and out – they were cut off by things with wings. Very I big, I think, really; but in the glass they looked like bats… I tried to get away because I thought it would fly out; but when it had covered all the globe, it disappeared. Then he came. He did not speak so that I could hear words. He just looked, and I understood.

“So you have come back? Why have you neglected to report for so long?”

I did not answer. He said “Who are you?” I still did not answer, but it hurt me horribly; and he pressed me, so I said: “A hobbit.”

Then suddenly he seemed to see me, and he laughed at me.

I found this passage to be fascinating. Tolkien has always been adept at crafting dream sequences, or pseudo-dream sequences. They feel enough like little myths in the center of a story that he slips into a distinctive, comfortable style: dark skies, tiny stars, tall walls. Things are evocative, but disconnected. This scene adopts this style fully, but as the readers makes their way through it, it becomes underlined by a distinctive sense of urgency. Rather than just a dream or vision of some kind, it becomes increasingly obvious that the danger is real. Pippin is in communication with Sauron himself.

Sauron’s depiction here is also really interesting. He is offhand and awful, casually cruel and powerful. His first line of dialogue makes him sound almost like a vaguely-annoyed middle manager. Nothing he does is overtly awful or overwhelming or terrifying. But at the same time, these three little lines of dialogue make him seem far more unsettling than Saruman ever was (despite the latter’s more desperate attempts at grandeur). Sauron here is casual, flippant. He doesn’t seem to care much that Saruman has not reported – he doesn’t even initially realize that he’s talking to someone different. When he asks Pippin who he is and doesn’t receive an answer, he doesn’t bother with cajoling or manipulation. He simply hurts him. And when he does get an answer, he just laughs.

It’s the inverse to Gandalf’s laughter in the last chapter. Gandalf laughs when a malicious spell is broken without success; Sauron laughs when he feels it has broken someone else. Tolkien doesn’t try to articulate how awful Sauron is, how powerful or full of grandeur. He just makes him cruel.

“We have been too leisurely. We must move.”

All of this would be enough to shock the chapter into motion. Gandalf realizes immediately that haste is of the essence (thank goodness we’ve left the Ents behind). Even after the palantír, though, there’s a sense of safety. Through a mix of sheer luck and hobbit toughness, Pippin managed to get through his encounter with Sauron unscathed (nice job, Pip!). If anything, their situation has improved. Gandalf no longer feels the need to probe around the palantír and possibly expose himself; Sauron is distracted by the fact that he thinks a jewelry-laden hobbit is likely locked up in Isengard. Aragorn takes guardianship of the palantír, leaving it in good hands and setting up some of the events of Book V.

And then the Nazgul arrives:

The bright moonlight seemed to be suddenly cut off. Several of the Riders cried out, and crouched, holding their arms above their heads, as if to ward off a blow from above: a blind fear and a deadly cold fell on them. Cowering they looked up. A vast winged shape passed over the moon like a black cloud. It wheeled and went north, flying at a speed greater than any wind of Middle-earth. The stars fainted before it. It was gone.

It’s another great description, deploying that most Tolkien-y of Tolkien-prose-tricks, long sentences punctuated by one or two short ones as the end. And the havoc that it causes is amazing. It can be easy to forget how much of a holding pattern Sauron has been in for the entire book, how much he felt like a distant, abstract threat. This was only compounded by Saruman’s increased prominence.

But then, in the space of three pages, we have Sauron speak to Pippin and a Black Rider flying over the camp, blotting out the stars. Gandalf seems frantic – in the space of a few minutes he changes plans, splintering the company into three and flying off into the night at high speeds, Pippin in tow. It’s a great end to Book III, a sense that danger and uncertainty has broken over the camp like a sudden, unexpected thunderstorm.

“All Wizards Should Have a Hobbit or Two in their Care”

Two more final points before we finish up. First – I appreciated how hobbit-centric this chapter is. It feels fitting for the book as a whole and it serves nicely to set up a more hobbit-heavy future for readers. Merry mentions Sam by name (the first time anyone mentions either Frodo or Sam in a while). Through the palantír, Sauron thinks that Pippin is the ringbearer. And near the chapter’s start, Gandalf mentions to Merry that he and Pippin were likely of great interest to Saruman, and weighed heavy on his thoughts.

The focus on hobbits – plus the sudden, unavoidable reorientation towards Mordor and Sauron – serves nicely to set up Book IV, which will backtrack to our other two hobbits, who’ve never let Mordor stray too far from their thoughts. It’s subtle, but it is a nice balancing act by Tolkien that he was able to make this chapter function as both a capstone to this book and a transition to the next one.

And finally, I also just really enjoyed Gandalf and Pippin together in this chapter. Their scenes together are always really delightful and they bring out the best in each other as characters. But I also appreciated how Pippin’s little arc in this chapter functions as a counterpoint against Saruman’s. It isn’t hard to read Saruman’s story as one that condemns overeager inquiry – he’s always trying to create, mold, shape, investigate. Gandalf even seems to confirm that “Alas for Saruman!” he says in reference to the palantír. “It was his downfall, as I now perceive. Perilous to us all are the devices of an art deeper than we possess ourselves.”

And at first, in this chapter, it feels as if Pippin is falling into a similar pattern. He’s resentful at the chapter’s start that Gandalf would not be more forthcoming with his information. When Merry chides him not the meddle in the affairs of wizards – “for they are subtle and quick to anger” – Pippin responds with exasperation. “Our whole life for months has been one long meddling in the affairs of wizards,” he says. “I should like a bit of information as well as danger.”

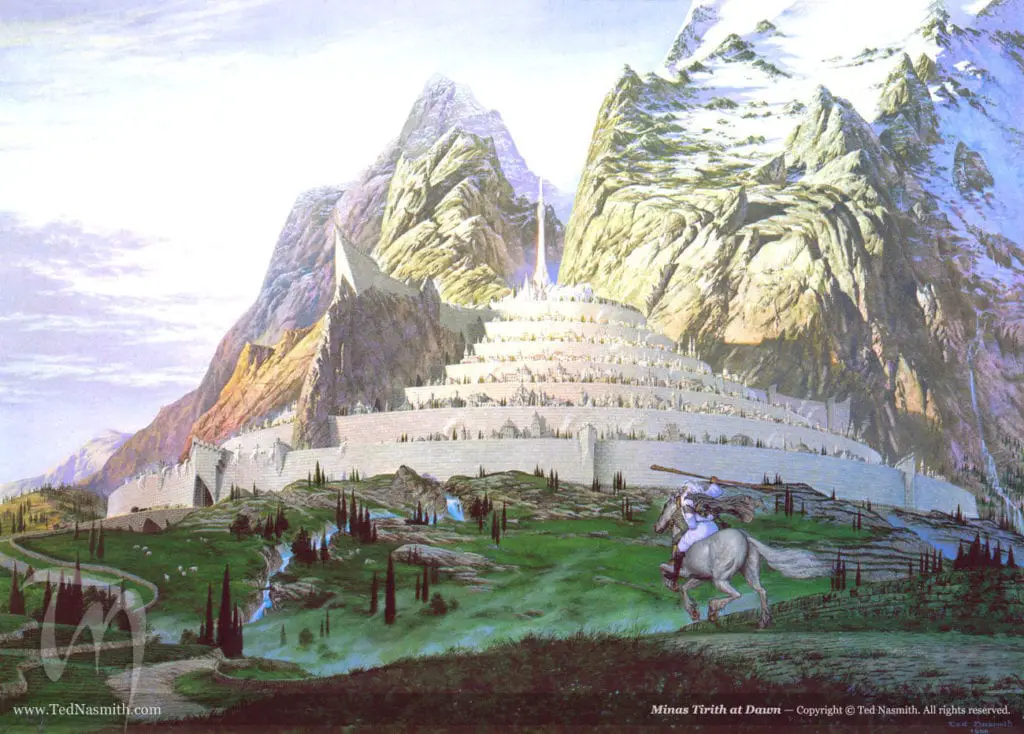

Pippin seems to be ultimately punished for this attitude: his curiosity exposes him to an all-powerful dark lord (and Gandalf yells at him). But at the same time, there’s a caveat to this message in the chapter’s coda. As Gandalf and Pippin ride towards Minas Tirith on Shadowfax, Pippin peppers Gandalf with questions. And Gandalf answers, willingly.

It’s a nice correction. Or maybe better, it’s a nice nuance. When Gandalf asks Pippin what he wants to know, this is how he responds. “The names of all the stars, and of all living things, and the whole history of Middle-earth and Over-heaven and of the Sundering Seas,” laughed Pippin. “Of course! What less?” Pippin’s knowledge is rooted in a desire to understand; Saruman’s in a desire to shape and to acquire. It’s such a key difference in Tolkien. As Gandalf said, “all wizards should have a hobbit or two in their care.”

Final Points

- I had forgotten (or never knew?) the etymological connection between Osgiliath and stars. It’s such a lovely name for a city.

- Another rare Tolkien naming failure: Tirion upon Túna. The first half is good; the second half is not.

- “A beautiful, restful night,” said Merry to Aragorn. “Some folk have wonderful luck. He did not want to sleep, and he wanted to ride with Gandalf – and there he goes!” Merry was honestly on fire this entire chapter. Merry is so great.

- I found it really sweet that Gandalf’s desire to look into the palantír and remove it from Sauron’s control was not based on pride or a conflict of power. Gandalf just really wanted to use it to look back at Tirion and Fëanor.

- The last bit of this chapter has always stuck with me: “As he fell slowly into sleep, Pippin had a strange feeling: he and Gandalf were still as stone, seated upon the statue of a running horse, while the world rolled away beneath his feet with a great noise of wind.” It somehow manages to be peace and ominous at the same time, though I couldn’t tell you how.

- Prose Prize: “Ents in a solemn row stood like statues at the gate, with their long arms uplifted, but they made no sound… Sunlight was still shining in the sky, but long shadows reached over Isengard: grey ruins falling into darkness.” It feels fitting to give the Ents one final appearance, before the Company move out of Isengard, and to make that final appearance feel so picturesque.

- We’ve made it to the end of Book III! It’s been such a delight talking about Tolkien to all of you. I’m looking forward to continuing it with Book IV – I was really fond of this section of The Lord of the Rings when I was younger, so I’m excited to see how it holds up on this read-through. We’ll check in on Frodo and Sam around mid-July. I’ve missed them!