Disco Elysium was an unexpected hit of the last year. A game that breathed some fresh air into the frankly increasingly stale RPG genre. One that delivered on the promise of Planescape: Torment. I wrote briefly about it after finishing for the first time. Back then, I avoided spoilers or anything that might clue a new player too much about the plot. Today, I will do the opposite and delve deep into the game’s themes. As such, major spoilers will follow – read at your own risk.

The main theme of Disco Elysium, as I see it, is the past. Dealing with the past and holding on to it. While the game is a detective story on the surface, the murder investigation isn’t the most important part of it… although it does still connect to this motif. But the heart of the game is loss, memory and moving on.

Revachol

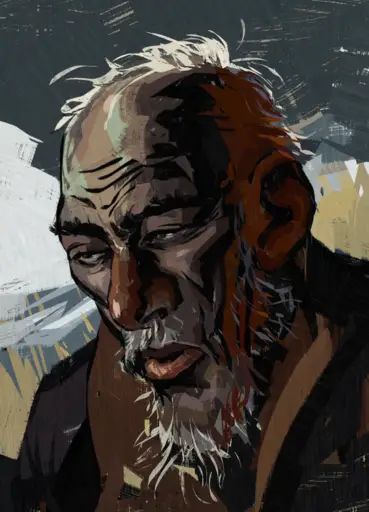

When our fearless protagonist steps outside the hotel in which he woke up as a blank slate, he is already confronted with the past. The streets of Martinaise are heavy with it. They still bear the scars of the revolution that died decades ago.

The legacy of the revolution has a strong influence on individual characters and informs the political situation the story takes place in. But more broadly, its looming presence creates the atmosphere of time standing still. Revachol (of which Martinaise is just a part) hasn’t moved on from the Revolution. It was destroyed, its soldiers killed, and its influence rooted out. But ever since then, the city has existed in a state of limbo.

The Coalition government that took over following the defeat of the Revolution keeps it this way for monetary reasons, and the practical results of it are all too predictable. Poverty, misery, lack of hope. Revachol feels like a place where nothing really changes. Nothing new happens, there’s nothing to look forward to. Everyone is scraping by. It’s exemplified in the “Doomed Commercial Area.” This dramatic name refers to a building littered with failed businesses: RPG designers, hairdressers, a gym, et cetera.

According to one of the two remaining business owners there, it’s a curse. A malignant entity that targets the inhabitants. The other one claims all these companies died on their own accord, due to mismanagement, incompetence, and market forces. We have the option to express our opinion, but the end result is the same – nothing works in Martinaise and Revachol in general. Every government, every political philosophy has failed in Revachol. Later on we do receive a hint it might have been more than just poor management… more on that below.

The Characters

Stepping into Martinaise with the mother of all hangovers, the protagonist is the fulcrum of the game’s question about the past and how to deal with it. He is a man haunted by his past, even though he can remember none of it. Indeed, there are strong hints that the utter obliteration of his memory happened on purpose. Both through the drinking and, possibly, exposing himself to the terrible force of the Pale. Harrier du Bois desperately needed to escape who he used to be.

Harry has led a hard life by all accounts, and he’s to blame for at least some of it. But the event that seems to have singularly accelerated his downward spiral is the break-up. The *ex-something* that haunts him. We spend much of the game having little knowledge of just what happened and we never really learn much when we do. He had a girlfriend named Dora and they broke up. This was at least partly caused by Harry’s alcoholism and erratic behavior, but the details elude us.

According to Harry’s deeply exasperated partner at the very end of the game, the breakup happened six years ago. That is a very long time to spend unable to move on, but it’s also clear that it’s just part of the problem. The issues that likely caused the breakup got worse afterwards – the alcoholism, working in frantic bouts of productivity, impulsiveness.

When memories of Dora resurface, it’s traumatic. Harry’s thoughts try to shield him from it with varying success. How Harry approaches it depends on us – he can blame himself, blame Dora, want to get her back or not. A fascist Harry can even blame the inherent infidelity of women.

Unless we manage to dodge all reminders of her (a difficult task), Harry will see her in a dream. Only it’s not really her. It’s an idealized image, full of grief and self-loathing. Nothing we do in the dream matters, because there’s nothing to be done anymore. As the dream-Dora says, they’ve done all they could and now it’s over. The only thing left for Harry is to move on, but he’s had a lot of trouble doing that.

The other character shackled by his past is the Deserter, Iosef Lilianovich Dros. Our perpetrator, the man behind the murder we’re investigating. Perhaps the last of the original Communards, who survived the brutal onslaught of Coalition forces by… running away. His courage faltered and he fled. This has haunted him ever since.

Years of living on the edge have turned Iosef into a bitter, hateful man. He watched the Coalition destroy the revolution and turn Revachol into a source of cheap labor, without any proper governance. He wanted no part of it and refused to try and find a new life. The game calls it out pretty unambiguously – Harry’s thoughts point out that he hated to see other people move on, be happy, try to live. He couldn’t do the same.

Of course, one can ask: how does one move on from that? Iosef saw everything he believed in and everyone he knew destroyed. Could he really have accepted it and tried to find peace with it? Maybe he couldn’t, but one way or the other, it turned him into a shell of resentment. Eventually he just started to hate everything and everyone, wrapping it in a veneer of Communist ideology.

At least a part of it is, of course, due to the Insulidnian Phasmid. It’s not clear how much. The most likely explanation seems to be that its pheromones kept him in locked in his teenage mindset, stewing in it. Harry can note that he seems oddly vital and “randy” for someone his age.

The Deserter is a clear and deliberate contrast to two characters: Harry himself and René Arnoux. René is a staunch loyalist and a representative of the game’s “fascist” ideology. Fascism doesn’t have a defined political party or ideology in the game, as such. Rather, fascism is defined by an idealized vision of a largely-imagined past, when there was a king and everything was right and proper.

René himself was a royalist soldier in the early days of the revolution and earned high honors for saving the dim-witted heir to the throne. Of course, the revolution prevailed and was then ground into dust by the Coalition.

René is thus a bitter old man, working a meaningless job as a watchman. It was given to him as a courtesy by the leader of the labor union, who has no need of it, as he knows everything that goes on in Martinaise anyway. The closest thing he has to a friend is Gaston, his old romantic rival, whom he seems to hold in contempt. An altogether more comfortable life than Iosef, but still marked with an obsession over the past.

Still, the game isn’t particularly subtle against the person Iosef is chiefly contrasted with – Harry. Iosef is a symbol of what Harry might become if he doesn’t find a way to let go of his heartbreak. A shell of a person, watching life from the sidelines, resenting others for moving on where he couldn’t. It’s too late for Iosef, who will likely not live for long once he’s arrested. But Harry still has a chance to pick up the broken pieces.

Whether or not he does is up to us, the players. It is possible to play him as someone who refuses to see anything wrong with what he’s done. Keep drinking, act like a “superstar cop,” blame everything on women and foreigners. Or we can guide him to trying to slowly dig his way back up.

The Pale

The third layer of the game’s delve into the past is a metaphysical one. It concerns the Pale. A defining feature of Elysium, the Pale is an endless sea of nothing that separates the pockets of human civilization. It’s spreading and will likely consume all life someday. During the course of the game, we might find out that Harry knows how it spreads. And one such point of origin is a two-millimeter hole in the world located in a church in Martinaise.

This memory comes to Harry as he investigates the hole. As he says, he has thought it before. At a kitchen table, talking to friends. He realized how the Pale spreads. Did it have something to do with how he lost his memory? The thought we can internalize after this realization suggests it might have. Perhaps Harry’s memory loss was at least partly caused by the Pale, not just the extreme quantities of alcohol he imbibed.

The nature of the Pale remains elusive, but we receive hints that humans cause it. We’re told that by… well, the Insulindian Phasmid. Thus it’s not clear how much of it is true. But even if the “conversation” with the phasmid is simply a reflection of Harry’s thoughts, it could mean he knows that the Pale is, but forgot.

A suggestion of just what the Pale is comes from the paledriver. She’s an old woman who has transported goods through the Pale for years, and her mind has suffered its consequences. She’s a jumble of other people’s memories, no longer taking any care to sift through them and separate her own. This suggests that the Pale is rarefied past. Pure information, ever-degrading.

We don’t know that for sure, but it would certainly suit the themes of the game if the looming threat to all life was, in fact, the past. Toxic past, encroaching on the present and threatening to consume it. Just like it destroyed Iosef’s life, can destroy Harry’s and hangs over Revachol.

How does one fight the toxic past? The first people to cross the Pale and survive used a psychological regimen resembling the creation of poetry. The church in Martinaise seems to have been built around the hole in the world in an effort to contain it. We don’t know why. But it’s no coincidence that we discover all of it in an effort to open a nightclub. As silly and downright inane as the entire enterprise might sound, it might be the last line of defense against… whatever it is on the other side of the hole. Something that the Pale is just a gradient of.

That’s because the nightclub is something new. Young people trying to start something, create something. Which, granted, does involve drugs. But they can be talked out of it and proceed to just start a nightclub. It’s silly, but it’s creative and forward-looking, which makes it stand out in Martinaise. All around it, people are burdened by the past and without much to look forward to in the future.

All of it ties into the Doomed Commercial Area and the supposed “curse,” mentioned below. The person who helps us investigate the hole in the world is a co-owner of one of the many failed businesses there. She ties the existence of the hole to their failure, but it’s clear that she does it because it gives her comfort. It wasn’t her fault, or her colleagues’ fault – it just couldn’t be done. Because nothing can work in Martinaise. Entropy permeates it too much.

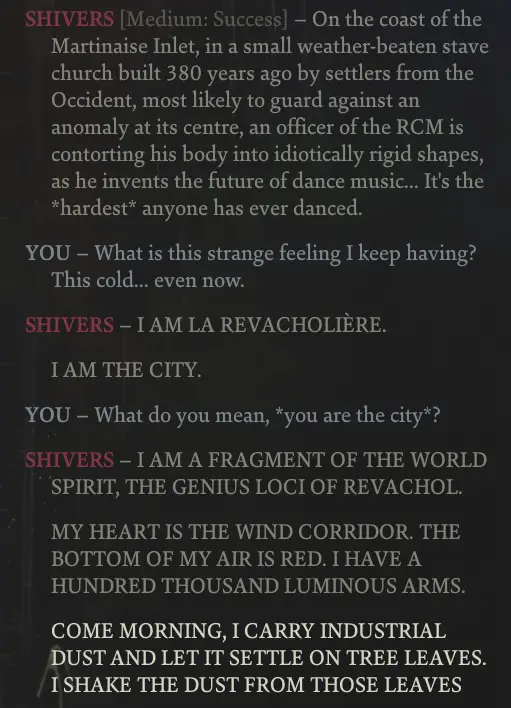

The church questline also includes a rather odd segment in which Harry can dance. Dance harder than anyone has ever danced. In doing so, he seems to finally escape his own head for a moment and… talk to the spirit of Revachol. Possibly. That’s what the voice of the Shivers skill tells him, at any rate. La Revacholière, as the voice calls herself, tells Harry that she loves him and asks him to protect her.

In the bleak landscape of Revachol, it’s one of the rays of hope. Disco Elysium can be a tragedy, but it can also be the beginning of a redemption story. Harry isn’t doomed yet and maybe neither is Martinaise, or Revachol, or even the world. It begins with looking forward rather than backwards, but the past is hungry and holds them all back. Can it be escaped? The ultimate message seems to be that it can, even if it won’t be easy.

Images courtesy of ZA/UM