Hello readers of Fandom Following. I am Michał, and now I get to inflict my opinions on an unsuspecting public. The first topic I will tackle is: power dynamics in fantasy, and Avatar: The Legend of Korra specifically.

So, what is this about?

When I say “power dynamics in fantasy,” I mean specifically the relationship between people who do have whatever fantastical powers the setting offers, and those who do not. Of course, just what this relationship is depends on a whole lot of factors. Are such powers present at birth? How common are they? How strong are they? It’s going to be a different dynamic when one in ten thousand people is born with the power to control others’ minds, and when a person can be granted the skill to make the crops grow with a song by their tribe’s totem-spirit. And so on, and so forth.

Nevertheless, I feel there’s a certain trend in media: they focus on the “supers.” Now, the reasons are obvious; we consume fantasy, sci-fi, and the like to experience things beyond what we know from the world around us. There’s also the power fantasy element – we want to imagine ourselves as the magical, powerful people. But it has always felt short-sighted to me. Statistically speaking, we wouldn’t be mages, mutants, psychics, or superheroes. We’d be Muggles. And we’d interact with the special people, one way or the other. I think too few works try to explore how that’d look.

I’ve always liked portrayals of “normal” people being cool and important in works of fantasy. Part if it is that I’m a sucker for martial arts, and a lot of fantasy takes place in pre-gunpowder, pre-industrial settings. Eventually, I started thinking about why and how things work this way in fantasy fiction. And here we are.

This is the first article in a series of three. I will be focusing on the Avatar franchise – Avatar: the Last Airbender and Avatar: the Legend of Korra, with a special focus on the first season of the latter, as it actually attempts to put this topic as the core conflict.

In the Avatar franchise, the power divide runs between those who are capable of “bending” and those who aren’t. Benders can manipulate the four elements using martial arts moves, based on various real-world martial arts. One needs to be born with bending in almost every case. The exception happens in the third season of Legend of Korra, where many nonbenders suddenly develop airbending. But it’s a result of the world-shaking events of the second season finale.

A predictable start…

Avatar: the Last Airbender deals with this rather typically. That is to say, it…doesn’t, at least not for the most part. We are given Sokka, the only member of the main cast who can’t bend. He feels insecure over it, which is put into focus for one episode, where he learns from a renowned swordmaster. That’s a single episode, however, and he’s otherwise comic relief with occasional moments of competence, mostly in the form of tactical thinking and engineering skill.

Apart from Sokka, nonbenders come mostly in the form of Fire Nation soldiers, the “bad” guys. The two most important nonbenders are Mai and Ty Lee – both of them capable of taking out platoons of benders. Generally speaking, the power divide between benders and non-benders is tailored to the needs of the plot. There are instances where the benders’ advantages are a plot point: Sokka’s insecurity, as mentioned, or an earthbending soldier bullying villagers. Still, by and large, the show takes it for granted – after all, bending is its major draw. Benders are in the narrative spotlight, as super-powered people tend to be in such stories. They do the important things, and non-benders (or other people with no powers) are just along for the ride, providing support.

And a less than typical continuation.

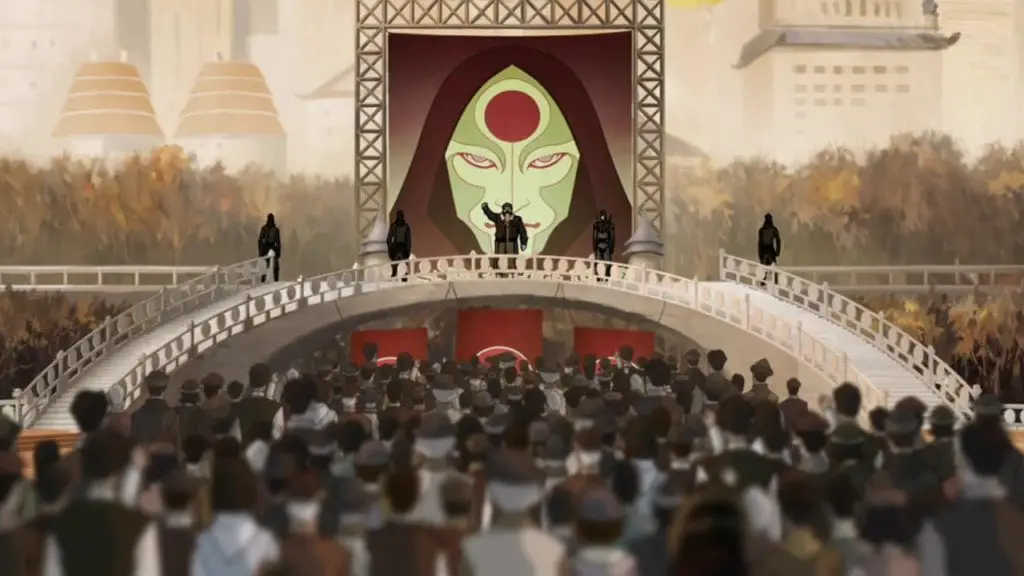

The first season of the sequel series, the Legend of Korra, promised to sharply deviate from this. The marketing surrounding it told of the Equalists – a revolutionary group of nonbenders who oppose bending itself. They would use advanced technology that had sprung up in the seventy years since Aang’s adventure, as well as the art of chi-blocking. Their leader was Amon, a mysterious, masked man, who we quickly learned could take away bending.

As you can imagine, the young and hopeful… well, young, anyway… man I was four years ago, eagerly anticipating the season. It seemed to promise me everything I wanted. It even started out well enough. In the first episode, we see bending criminals bully and extort a nonbending craftsman. Korra displays an ignorant and insensitive attitude towards the disaffected nonbenders. In the third episode, we see more of the criminal gangs that use bending, and Amon reveals himself to the audience.

What the benders have to say…

That, unfortunately, is as good as it gets. Nonbenders are unhappy, and many of them follow Amon, who claims to have lost his family to a firebender. But the expected exploration of the conflict beyond that never happens. Amon makes his speeches – but no one ever contests nor affirms them.

None of the bending heroes care about what he says, beyond “losing my bending sucks, I hope it doesn’t happen to me.” Korra starts the season as being largely ignorant of how non-benders live, but that never changes. Her attitude towards the conflict appears to be purposefully set up with room for growth and understanding… yet none occurs from what I can tell. To Korra, the Equalists are just an army of mooks whose leader she opposes. Mako and Bolin, her fellow pro-benders and first members of the new Team Avatar, grew up on the streets. They should, one would expect, know something about the issues that would drive nonbenders into a revolutionary movement. But if they do know, they certainly aren’t telling. Again – their concern is not losing their bending.

And the other side of the fence.

But that’s benders. How does it look from the perspective of the nonbenders? One might expect that a season where disgruntled nonbenders form the core of the antagonists would zoom in on how they see themselves in a world defined by bending. Indeed, that would be an obvious departure from the norm if that were the show’s intention. Unfortunately… it doesn’t really happen.

There are three named non-benders in the show: Asami Sato, her father, Hiroshi Sato, and Tenzin’s wife, Pema. Asami and Pema, the two non-benders on the protagonist’s side, don’t really articulate any opinion on the conflict. Asami opposes her father because she’s not too crazy about an armed revolution and taking people’s bending en masse. Pema’s role is minor in general. The one scene these two women have with each other, they spend… talking about baby cramps.

Hiroshi, a self-made industrial potentate, develops the Equalists’ weaponry, because a firebender killed his wife (firebenders rack up quite a bodycount in the season’s backstory). Which is all we get from him; he’s mad because his wife died, and the benders had “ruined the world”. Mad to the point of becoming a raving bigot.

The unfortunately-faceless masses.

The rest of the Equalists get no names or voices, apart from Amon, who isn’t actually a nonbender. Early on, we see a street demonstration, where an angry protester shouts some rather generic complaints about non-benders being second-class citizens. As the season moves on, Amon is the only one to express their grievances.

There’s also a man known as “Lieutenant,” who fights using electrified kali sticks. Which is pretty rad, if I do say so myself, but there’s nothing to him beyond that. We don’t know why he chose to serve Amon and fight against bending. Did he lose his family or friends to A. Firebender’s murder spree? Did he lose his job because of a bender? Or is it a philosophical thing? By and large, the Equalists are a mass of bodies more impersonal than the first show’s Fire Nation. Which is the sad thing: despite its goal, Book One of Legend of Korra really has less nonbender agency than The Last Airbender.

Where it goes really wrong.

As I mentioned above, Amon leads unhappy non-benders while not being one of them himself. He turns out to have been a waterbender all along. His bending-removal ability is a form of bloodbending, and his motivation is, apparently, his father’s abuse. It’s never made too clear, but we do know his mob boss of a father had his own bending taken away by Aang, and tried to mold his sons into instruments of revenge. This somehow led Amon to want to eradicate bending itself. Was he honest? The show doesn’t really tell us definitively.

This has a rather disastrous effect on the plot as a whole. A conflict that had shaped up to be about the relationship between nonbenders and benders actually boils down to a powerful bender’s personal drama. This means that the narrative spotlight is taken away from nonbenders for good, not that it was ever truly on them in the first place.

Perhaps if we’d got a proper portrayal of the conflict, with nonbenders on both sides showing their perspectives, it wouldn’t have been so bad, but as things stand, a rather thin premise is blown apart entirely and replaced by a cheap twist. Korra’s glee when she finds out about Amon is palpable – suddenly, it’s bender against bender. She just has to expose Amon as such. The order of the world is restored. Once again, it’s benders doing the important things, and nonbenders are their sidekicks and minions.

Why is it a problem?

You see, as I hinted at in the beginning of the article, the thing “normal” people lack in such stories tends to be agency. They don’t shape the narrative, generally. They might be major characters, but they stand behind the special ones. Sokka engineers the plan to destroy the airship fleet, but Aang defeats Ozai. Lando Calrissian blows up the Death Star, but the Jedi and the Sith truly decide the fate of the galaxy. And so on.

The first season of Legend of Korra looked like it might change it: nonbenders would put in motion major events, and a nonbender would challenge the Avatar herself. When Amon is just a powerful bender acting out on his own trauma… the story falls into a well-trod path. He’s simply another typical villain, whose minions just happen to be exclusively non-benders.

When he effortlessly crushes his lieutenant with bloodbending, he says that he had served him well, before throwing him aside. A rather apt metaphor of the nonbenders’ ultimate place in the story and the world. They can only do things when led by benders, and if they want to change the world, they better hope a bender agrees.

What could have been.

What might it have looked like, if the season had delivered on its promise? It’s hard to say. The relations between benders and nonbenders resemble both racial divides and class divides. No real-world analogy is going to be ideal, of course, since we’re dealing with supernatural powers. Bending has no downside, the way magic powers often do, and so benders just have more capabilities and opportunities than nonbenders. It’s just the way their world works, and it’s easy to imagine why nonbenders might be resentful over it, and how unfair social structures might arise from it. The closest we get to it is when Tarrlok orders the metalbending police to round up protesting non-benders.

Such abuse of power is easy to imagine: there’s only so much non-benders can do against a group of benders concentrating their power on them. One can see how a martial elite might use it to keep their subjects compliant. The Equalists’ technology, which enabled them to take on benders, resembles the way the invention and development of gunpowder weaponry changed the social dynamics between the old warrior ruling classes and the commoners (even if it didn’t happen as quickly as it’s generally believed), as well as the societal shifts brought about by an industrial revolution.

In any society, there are certain lines that determine people’s standing and privilege – wealth, lineage, gender, race. In a world where some people simply have supernatural power from birth, you might expect that this line would overshadow any other to some degree. And it’s worth exploring. But, alas, it wasn’t, and in all likelihood it won’t be in any further content we get for the Avatar franchise.

The biggest potential, though, was perhaps from a meta perspective. Avatar: the Last Airbender was a typical show in many ways; it took a well-known story structure and executed it with considerable skill. Aang’s journey was that of many heroes. The story of an eager young Avatar – Aang’s opposite in many ways – taking on a revolution of those such stories normally overlook had an enormous potential for subversion and smashing expectations. The Legend of Korra bowed to them, instead. Stories where the heroes need to examine their own privilege and accept that the people they oppose have legitimate grievances, being kept down by a society that benefits the protagonists, are rare and valuable. But Book One was not such a story. And its subsequent seasons ignore this topic entirely.

What’s next?

That concludes the first work of fiction I decided to look at in my exploration of power dynamics in fantasy, and unfortunately, it’s not a particularly positive look. The Avatar franchise’s attempt at touching on the subject I talk about was a failure, by and large. Next time, I will discuss the way in the Dragon Age series of video games handles the topic. It makes many mistakes in its own right, but overall it’s more varied and successful.