Co-written by Gretchen and Kylie

Here at the Fandomentals, we’re all about our, well, fundamentally sound fandom analysis. We find taking deep dives into the media we consume to be a fruitful endeavor, since these are what serve as a platform from which cultural conversations occur. Along the way, we’ve learned about different lenses of analysis, to the point where finding an article that doesn’t mention “Watsonian” or “Doylist” is a rarity.

This is for good reason; these represent two different lenses for analysis, and the reasons for evoking them and the conversations that result serve different functions. Loosely put, a Watsonian lens allows the reader/viewer to understand the text itself, almost “through the eyes of the characters,” while a Doylist lens is the meta-text, or what the author is trying to accomplish in their storytelling. The question, “why didn’t Alex and Maggie communicate about wanting children during their many months of engagement” lends itself to one type of explanation. “Why did the Supergirl writers not have Alex and Maggie communicate about wanting children during their many months of engagement” is quite a different one.

As Julia explained in her previously linked piece, understanding both these lenses is where balanced conversation lies. It’s good to be aware of the man behind the curtain, but there is also something happening on-stage, too. And that something is consumed as entertainment, whatever the motivation behind the story may have been.

However, there’s something we’ve been leaving out of this “balanced dialogue” equation. Or rather, something we all tend to do in any conversation regarding fandom, but something that’s never been giving a label. It’s related to our discussion of “unfortunate implications” and why they matter, but it’s not just a shade of Doylism.

No, we’re speaking of the third lens of analysis, reader response.

What is this?

In the broader field of literary theory, reader response is a form of literary criticism that found prominence in the 60s and 70s and which focuses on the reader’s (or audience’s) response to a piece of work. The basic idea is that the only meaning that matters is the one the readers/audience create for themselves from a piece of art, rather than what an author intends or what is present in the text itself. It started off in literature, but it can be used as a form of criticism for pretty much any art form, whether visual, written, or auditory.

Think of art like a spoken conversation (Gretchen is a linguist, so this is her go-to analogy). When two people talk to each other, there are always three levels one can look at: what the person speaking wanted to communicate, what they actually said, and what the other person heard. Say two people are in the kitchen and one notices that the trash is full. (We’ll call them Cheryl and Larry, for no particular reason we can fathom.)

Larry: *thinks to himself that if he doesn’t say something out loud, he’ll forget that he needs to take the trash out.*

Larry: We need to take out the trash.

Cheryl: *hears an accusation that she hasn’t taken the trash out yet.* I’ll take out the trash in a minute, jeez!

Notice that Larry didn’t actually say what he was thinking, which was that he wanted to remind himself to take the trash out later. However, Cheryl—maybe because she’s in a bad mood or Larry was just being stupid a minute ago, or maybe because she’s lived within an oppressive system that expects her to cater to men—heard something very different. Yet, neither one of these is the same thing as what Larry actually said.

What someone hears isn’t always equal to what was said or what the other person meant. That’s the gist of reader response, that people who engage with a piece of art or media can come away with a different impression, interpretation, or reaction to a piece of media than what a creator intended or from what was explicitly said/shown. This happens because we all bring our own baggage and experiences into our interactions with media, and these sometimes don’t line up with those the creator brought to their work.

Admittedly, sometimes audiences having a different takeaway has nothing to do with baggage. Creators can be unclear or miscommunicate their intentions; sometimes the medium they chose lends itself poorly to what they’re trying to say or, if they have a production team, someone else may have added or taken away aspects that muddied the message.

Sometimes audiences simply misunderstand the message. They may not have the appropriate social or historical context, or lack pieces of information for the message to make sense. None of this is anyone’s fault. It isn’t even a bad thing, really—just a normal part of human communication, be it art or spoken conversation. Language in all its forms is both flawed and limited, so it should come as no surprise that wires get crossed.

One of the values of taking a reader response perspective is the acknowledgement that wires do get crossed. By taking a closer look at what audiences hear and react to, we can see where misunderstanding on their part or miscommunication on the creator’s part may have taken place. Ideally, creators can use a reader response perspective to make course corrections. By understanding how audiences perceive their work, they can adjust to clarify or correct what they’re saying in order to line up more fully with their intention.

More than anything, reader response as a tool of media criticism highlights the impact of stories on audience members. Stories have great power to shape how we perceive ourselves, others, and our world. That’s why we talk so much on The Fandomentals about why stories matter.

Authorial intention can only get you so far when you’re talking about the representation of marginalized communities, for example. The team behind The 100— and the rest of the shows that buried their queer women in the 2015-2016 season—may not have meant to send a message that the lives of queer women don’t matter and they deserve to die rather than have happy endings, but that sure is the message LGBTQ+ audiences received. Given the significant and lengthy history of LGBTQ+ folks being denied happy endings to service a larger heteronormative agenda, how could that not be what people heard? It’s the same message they’ve been hearing all their lives: you don’t matter, you’ll never be happy, you deserve to suffer, etc.

From a reader response perspective, the damage caused to the LGBTQ+ community and women-loving women viewers in particular matters more than what the creators meant to say. Is “anyone can die” really worth more than the hurt caused to thousands of real queer women watching the show? Or take the overwhelmingly negative response to the seemingly now-tabled HBO show Confederate. No matter what HBO and the showrunners might have intended for that show to be, at the end of the day, the potential damage done matters more.

Is entertainment value worth more than reinforcing sexist stereotypes and patriarchal structures? Do cool CGI and poor script editing really make up for the awful writing of female characters and racist caricatures? Most creators are well-intentioned, to be sure, but that doesn’t mean that they can’t be well-intentioned and hurtful. Reader response makes room for discussing impact regardless of intention. It’s the ‘cool motive, still murder’ of media criticism.

Danger Danger!

After that explanation, it can almost seem as though reader response is the only lens that matters. Characters are not real, but the people reacting to them sure are, so why wouldn’t we want to leverage the angle of analysis that prioritizes those reactions? Forget Watson and Doyle, we have masses of people we’re talking about here, and we’d prefer if they don’t feel like crap.

Yet that’s part of the problem. Reader response can tend a bit towards argumentum ad populum, or conversations centered around the idea of, “well most people thought this.” It is important how something tends to land, of course, but it’s equally important to remember that this lens doesn’t get at any kind of objective truth. Reader response is supposed to be wading deep into subjectivity, since it’s all about what individuals “hear.”

This means, however, that positive and negative reader responses don’t outweigh the negatives and positives of media. Well-loved/“fun” books and movies might still have messaging that plays into a rather outdated morality, for instance, or media that’s pretty problematic can also have useful takeaways or elements that are compelling for some to engage in. There’s no right or wrong way to have that engagement, of course, and it’s entirely personal where the line is between “problematic fave”, “guilty pleasure”, and “trash show” (and whatever lies in between).

In a way, a focus on reader response should highlight that fact. But the danger is in ignoring the fact that there is a story being told, and the author has a reason for telling it. A “death of the author” mentality only goes so far, or else we’re looking at an echo chamber of popular reactions. We can recognize the different reasons for/methods of media engagement, or make a case for our own. The value of this lens is having full awareness that it is our own. It’s not to give us carte blanche to ignore the story itself or write off its value for others (Or, conversely, insist that its value trumps others’ negative responses.)

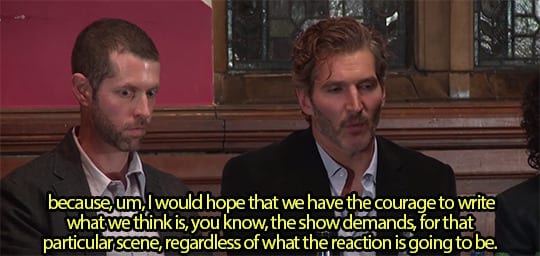

On the other hand, we don’t believe “I didn’t mean it” can be used as carte blanche for a creator to avoid engaging with negative reactions from audience members either. Lack of intentionality on a creator’s part doesn’t erase any damage done and isn’t a substitute for active listening and apologizing. Words, and media, can be hurtful, damaging, and play into negative tropes or stereotypes whether a creator means them to or not, and relying solely on intentionality in a situation where real life people are hurt isn’t the most constructive or helpful way forward.

So what is?

Damned if you do?

Getting back to the conversational analogy we used earlier, if a friend accidentally says something hurtful, the most effective response for them is to apologize and ask questions to determine where the miscommunication happened and how they can be clearer next time. They can explain what they meant for sure, and the hurt person can acknowledge their lack of intention to hurt them. At the same time, “not meaning to” should never be used as an excuse to avoid engaging with someone who is hurting. You wouldn’t want your significant other to shrug, say “I didn’t mean it,” and walk away expecting you to just suck up how you feel, so creators of media shouldn’t behave that way either.

We’ll put it another way: if I accidentally slam a door on your toe, you’d want me to say sorry and promise to be more aware in the future. Your reaction may change depending on whether you knew I did it on purpose or on accident, but the reality is that I hurt you regardless of my intent. The sentence, “I didn’t mean to slam the door on you, so your foot shouldn’t hurt” is ludicrous. If apology and greater awareness is normal behavior for physical injury, why should we expect any differently from content creators when they accidentally cause emotional pain to their audiences?

What we’re getting at is that there is a level of responsibility in creating stories for people to consume, whether intentionally to shape people’s minds or just for ‘pure entertainment value.’ Yes, there is a story being told and there is an intended response. However, that doesn’t mean someone can create something then stick their fingers in their ears and their head in the sand when it comes to negative feedback.

But what exactly should they do? Give up, go home, and never make another tv show again? If that were standard, we’d probably have no content creators left simply because everyone makes mistakes. While there’s no specific outline of the best way to do it, listening to what didn’t go over well and sincerely apologizing is a reasonable expectation. It’s what one of us would do in a one-on-one conversation or in the case of physical injury, so let’s start there.

Other than that, there’s no clear cut way for a content creator to proceed. The options vary depending on what genre or medium you’re involved in (producing a TV show versus writing a book). However, a direction of increased awareness and continued engagement with hurt communities and fans goes far no matter what your art form is. There’s a reason Javier Grillo-Marxuach has been embraced by hurt The 100 fans after Lexa’s death where other showrunners have failed to do so.

Accidentally hurtful creators may not be able to win over every hurt fan; that’s an impossible goal and setting oneself up for failure. But there’s a whole lot of nuance between making it right with everyone and completely ignoring the unintended implications and accidental damage of one’s work.

Creator responsibility to respond appropriately doesn’t justify dickish behavior on the part of the fans, either, but that’s a whole other conversation. (One Gretchen plans on having pretty soon, so stay tuned for that.) For now, we’ll just say that there’s a tension between letting creators fail and learn from it, and letting them off the hook entirely for implications, intended or otherwise.

What a Tool

So are we saying that reader response is the only valid way to critique media? Far from it. At the end of the day, reader response analysis is another tool in the media critic’s toolbox. It’s an important one to be sure; it provides balance to Doylist and Watsonian analysis and prevents the audience’s voice from being silenced in the discussion of what media means or why it matters. No one layer of analysis is inherently more valuable than any other, though one may be more relevant to a given piece of media at any one time. What’s important for us is that they all deserve attention and discussion without assigning one as automatically more meaningful all the time, forever, and for all art.

Using the analogy of a conversation again, the speaker’s intention isn’t always the most important aspect of a discussion, nor is what they said. But neither does that mean that what the listener hears automatically takes precedent either. Each of those three layers has value, importance, and is worthy of discussion and analysis. They inform each other and play off of each other. One might be more relevant or significant for a specific piece of media (like reader response is for Lexa’s death and the Spring Slaughter) at any given time, but that doesn’t mean the other two somehow disappear or shouldn’t be talked about.

To use another analogy, Doylist, Watsonian, and reader response analysis are like music. Sometimes the melody takes prominence, other times the harmony or the rhythm, but that doesn’t mean the other two don’t matter at all. It’s the interplay of all three that gives media analysis it’s beauty, at least for us.

And just because it’s reader response doesn’t mean that it can’t be questioned. Reader response is primarily a discussion of subjective reactions, whether individual or collective, and we think it valuable to talk about where those reactions come from and how changing one’s reaction or perspective can impact how one perceives a piece of media. As Kylie talked about recently, we want to be open to changing our minds about pieces of media that we may have strong opinions on either way.

The “your mileage may vary” approach we’ve taken in the past about aspects of media we engage with is just another way to talk about reader response. We find that outlook useful, especially because it allows for greater and continued discussion. Acknowledging reader response isn’t meant to be a way to shut people down, but, rather, as a means of being honest about where we’re coming from at any given moment. “Here’s my reaction, tell me yours and we can talk about why we think the way we do.” With reader response, there’s no need to source one’s opinions in the text itself or claim they’re the author’s intention.

It’s about owning your own subjectivity when it comes to reacting to media and being willing to listen to what other people have to say. It’s about asking questions, using curiosity as a tool to understand why other people might interpret a show or character arc differently. At its best, reader response is a starting point for understanding other people and engaging with them in honest and respectful ways.