A deadly class trial…!

High school is a tough time for everyone. Puberty makes kids’ skin break out, self-esteem issues are crazier than a roller coaster ride, and forget about trying to balance homework, a social life, and extracurriculars.

Then try throwing some murder into the mix.

Danganronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc, developed by Spike Chunsoft originally for the PSP and then later for the Playstation Vita, follows the story of fifteen high school students admitted to Hope’s Peak Academy, which only brings in the best of the best: the “Ultimate” students. The protagonist, Makoto Naegi, gets in as part of a lottery drawing, making him the Ultimate Lucky Student; amongst his classmates are the Ultimate Gambler, the Ultimate Fanfic Writer, and the Ultimate Pop Sensation, to name a few.

But when Makoto makes his way into Hope’s Peak for the first time, he faints, and wakes up with his classmates only to find the exits have been sealed. Windows are boarded over with thick metal sheets, the main entrance is covered with a huge metal shutter, and then things get worse: along comes Monokuma, a talking robotic teddy bear with a penchant for pain.

The students quickly learn that the only way out of the school is murder. Should anybody kill a classmate and get away with it, they get to graduate from Hope’s Peak and leave safely… but if they’re found out, they face Monokuma’s brutal punishment. If the Ultimates fail to figure out who killed their classmate, they face death themselves.

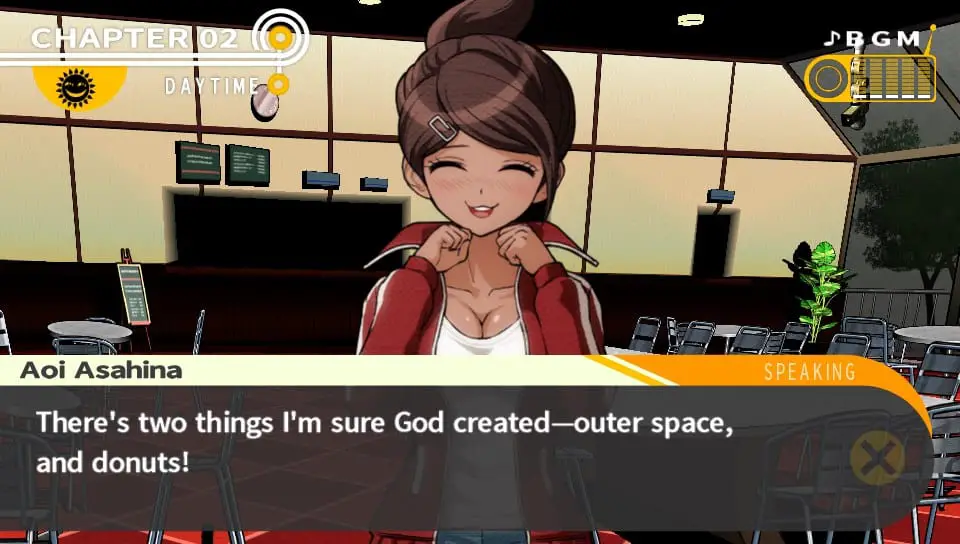

Danganronpa oozes style. Each area of Hope’s Peak is lit up in a different vibrant color, and the menus have a distinct visual finesse to them that evokes Persona 4‘s own vibe without feeling like a ripoff. The 2D character portraits, all drawn anime-style, are high-resolution and gorgeous, and the strong use of colors from Hope’s Peak continues in each of the character designs. Kyoko’s outfit stands out in particular, with character designer Rui Komatsuzaki using a great combination of purples and blacks to keep it distinct; Junko, as well, shows a great use of color and style. While appropriately distinct, none of the characters ever look completely outlandish despite the game’s premise. Amusingly, while in the 3D-rendered Hope’s Peak exploration modes, characters remain in 2D, looking like cardboard cutouts; it’s strange, but adds to the game’s charming weirdness.

The execution scenes, however, are the highlight of the game’s graphics. In stark contrast to the exploration’s computer anime style, these scenes use hand-drawn art to show the deaths of some characters. They’re brutal, but never gruesome, and always with a touch of humor. The ideas behind them, too, are completely out of left field–I won’t spoil them, but suffice it to say that although twisted, much of the game’s draw lies in these scenes.

The music, done by Masakumi Takada (killer7, God Hand, No More Heroes), has an electronic feel to it, but also does a great job of selling the game’s bizarre combination of school days and murder mysteries. Unfortunately, while the music itself is great, the voice acting is hit-or-miss. For instance, Brian Beacock’s Monokuma manages to be humorous and sinister without ever being annoying, but Jason Wishnov’s Byakuya spends the entire game sounding bored out of his mind. It’s jarring to hear some characters fervently debating the latest murder, only to have several of them sound as if they don’t care despite dialogue suggesting otherwise.

Despite some vocal missteps, the characters themselves are memorable. Each of them fits within a typical anime archetype, from the martial arts guru to the cripplingly-shy younger girl to the snooty rich kid to the biker gang leader. As the game progresses, though, each character becomes more than just their role. Some of the developments are simple; for instance, swimming enthusiast Hina loves donuts. Others are a lot more interesting, though I’ll refrain from spoiling anything.

However, one character sticks out as particularly problematic when it comes to LGBT issues. Spoilers follow in italics:

Chihiro Fujisaki spends the majority of the game trying to work up the courage to be herself. She constantly compares herself to the rest of the group, and when she begins opening up to Makoto, reveals that she’s tired of being weak. However, when she becomes part of a murder investigation, it’s established that Chihiro was born male; she found herself to be quite weak, and in an attempt to avoid bullying, hid within her femininity. She lived life as a girl from then on, because to her, only women were allowed to be weak. It’s ambiguous, but the game hints that when Chihiro would finally become strong in both body and mind, she would return to identifying as male.

From the point that this is established, the game’s characters begin to refer to Chihiro with male pronouns, and continue to for the rest of the game. From a Western perspective, this is blatantly offensive, as is the game’s equating femininity with weakness to the point of pushing what seems to be a transgender role into a mind-boggling gender reveal.

It is important to keep in mind, however, that the game takes place and was developed within a distinctly East Asian context, a vastly different society than the West. While that doesn’t excuse the potential for problems, especially to trans individuals, it also means that the game is likely critiquing Japanese society, in which gender roles are much more strictly enforced than in, say, the United States. Even so, it’s a sensitive matter that bears mentioning.

The game is separated into several distinct segments: Free Time, Investigation, and Class Trial. Once the introduction is finished, players may control Makoto and explore the 3D-rendered Hope’s Peak in first-person. Players familiar with Japanese RPGs, particularly the more-recent entries in ATLUS’ Persona series, will feel right at home in the Free Time segments. Similar to the Social Link system in that series, players controlling Makoto will spend time with the characters and learn more about their motivations and backgrounds. It’s a pretty cool little system that uses the characters’ need to escape as justification for them spending time together, although it’s a little odd that players can spend time in the Hope’s Peak store to buy gifts for the Ultimates. Furthermore, spending time with other characters allows Makoto to grow and learn new skills for the Class Trial segments, which I’ll cover below. While the characters begin as typical anime archetypes (the sporty girl that lacks intelligence; the rough-and-tumble biker; the girl who is massively insecure in everything she does), interacting with them in the Free Time segments fleshes them out and brings them past their archetypal roles. Generally, Free Time allows for two character interactions per day, and while the game doesn’t actively keep track of any sort of calendar, after a few days the investigations will start.

Investigations come about whenever a character is murdered, and as one can guess, it’ll happen multiple times throughout the story. These segments share the same style as the Free Time periods, with a focus on exploring crime scenes and related areas (think Ace Attorney‘s pre-trial prep periods). Danganronpa never makes it too difficult to investigate, though–by pressing the triangle button in any given room, players can see what items they can interact with, alleviating the need to scour every nook and cranny of any given room. Instead of taking out challenge, though, some items that are highlighted as approachable aren’t actually relevant to the murder cases.

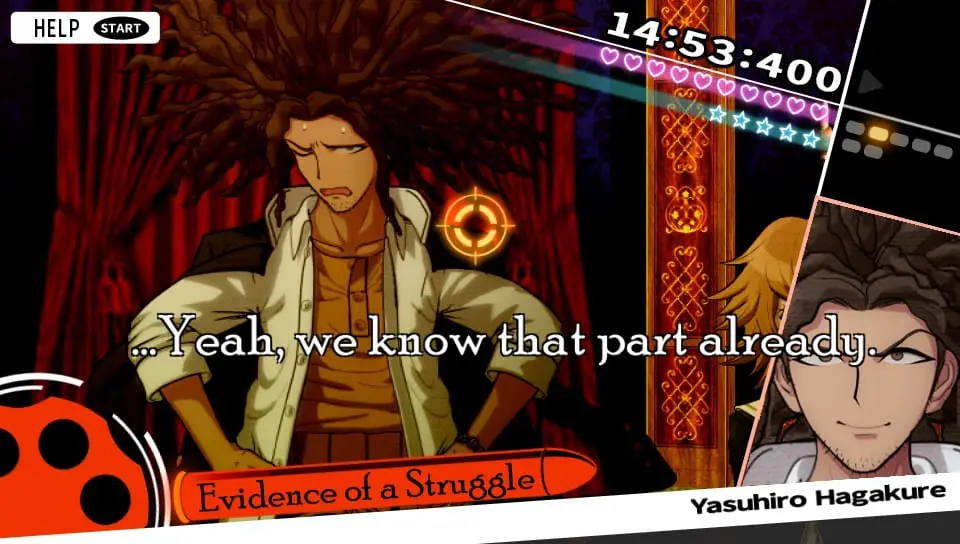

Finally, whenever Monokuma decides–which conveniently is always after every clue has been gathered–the Class Trial begins. All the Ultimates gather, and take the elevator down to the school’s courtroom: an opulent throne room, where all of the students must stand facing each other and get to the core of each murder. These segments are where the game gets the bulk of its interactivity. Instead of Ace Attorney‘s straightforward court narratives, the debates in Danganronpa are done through a mixture of minigames: shooters, rhythm games, and comic book creation. When confronting Makoto’s classmates, their statements will fly across the Vita’s screen, and either by touching them or aiming and pressing a button, players will shoot evidence (“truth bullets”) and point out contradictions; sometimes conflicting thoughts will block the way and need to be eliminated. On occasion, Makoto will need to call up a thought, and letters will fly across the screen until shot down, piecing together the necessary word. When the Ultimates get stuck in denial, their protests will fly across the screen and players will need to tap buttons in tempo to shoot them down until Makoto can get to the core of the problem. Finally, when the case has been solved, a comic book will pop up, and players will pull scenes from the game and place them in their proper contexts. This is perhaps the most challenging parts of the gameplay, although it’s not due to mind-boggling cases; the icons given for the comic book parts are not particularly detailed, making it difficult to determine what exactly each icon is trying to portray.

That’s the main problem with Danganronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc: the cases themselves aren’t very difficult. The game’s intriguing, to be sure, and finding out character motivations is fascinating, but the actual mysteries themselves–save perhaps the very final trial–are disappointing in their difficulty. They’re not as frustrating as, say, Ace Attorney‘s insistence on pointing out every single tiny contradiction, but they’re also never as complex as that series’ puzzles are. I hate to compare the two, and indeed they’re radically different games in style and in plot, but on a sheer difficulty level Danganronpa is one of the easier mystery games I’ve played. Having played Spike Chunsoft’s previous effort 999: Nine Persons, Nine Hours, Nine Doors, it’s a little of a disappointment, although it must be mentioned that 999 is done by a different team.

That isn’t to say Danganronpa itself is disappointing; far from it. Despite being spoiled on the overarching plot, I found the resolution to still be quite enjoyable. Even having the mastermind’s identity spoiled for me, I still found the final confrontation to be captivating, particularly the characterization of the villain. It hovered somewhere between ridiculous and terrifying, and I think that’s perhaps the best way to sum up the game: a little bit over-the-top, a tad scary, and all-around compelling.

Good

-Overarching plot carries intrigue throughout the game

-Characters become more than just anime archetypes

-Gameplay ideas are intriguing and refreshingly off-beat

Bad

-Cases themselves are easy, leaving some to be desired

-Gameplay itself isn’t particularly in-depth, at least on default difficulty

-Some of the vocal cast leave much to be desired

Play it if: you’re looking for a strong mystery game, something that simply oozes style, or you want something a little offbeat.

Danganronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc was completed over several weeks, with an approximate playtime of 23 hours. It is available for Playstation Vita, published by Spike Chunsoft.