We’ve made it to Rohan! I have been looking forward to this since we started the re-read a year ago (!) and “The Riders of Rohan” doesn’t disappoint. Where “The Departure of Boromir” very much feels like a wrapping-up of the loose ends of The Fellowship of the Ring, this chapter feels like The Two Towers stepping into its own rhythm and identity. It is a chapter with both a very wide and very narrow scope. It opens as a pure chase scene: Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli run down through Emyn Muil and onto the plains of Rohan in pursuit of Merry and Pippin. Yet as the chapter unspools, it slowly reveals some of the key aspects and themes to come. Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli become a more coherent team outside the context of the Fellowship. Through Éomer we get our first look at Rohan. Both Saruman and Mordor become more tangible realities instead of distant, abstract threats. A new stage of The Lord of the Rings starts to come into focus.

Rohan

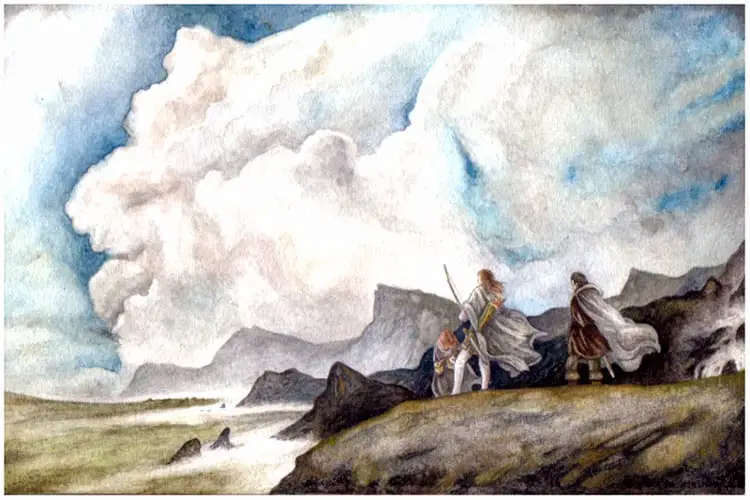

As we’ve probably all come to expect from Tolkien, we get our introduction to Rohan – and by extension, The Two Towers – through landscape.

At the bottom they came with a strange suddenness on the grass of Rohan. It swelled like a green sea up to the very foot of Emyn Muil. The falling stream vanished into a deep growth of cresses and water-plants, and they could hear it tinkling away in green tunnels, down long gentle slopes towards the fens of Entwash Vale far away. They seem to have left winter clinging to the hills behind. Here the air was softer and warmer, and faintly-scented, as if spring was already stirring and the sap was flowing again in herb and leaf.

It’s a rather promising start. Landscape in The Fellowship of the Ring – especially in the in-between sections when the Fellowship was traveling – had a tendency to be ominous. There was the harsh emptiness of Hollin; there were the stark hills of the Brown Downs. More often than not the landscape served as an isolating tactic for the Fellowship, conjuring up images of a barren, hostile landscape. So when they enter into Rohan, there is almost a sense of relief. It’s a large grassland with creeks that are “tinkling away in green tunnels,” the dead of winter is replaced by hints of a “softer and warmer” spring. There is a sense of relief in entering Rohan, which pairs with Aragorn’s complimentary description of the Rohirrim that live there.

But almost immediately afterwards, we also get a sense of wrongness and confusion. When listening to the earth (a neat Ranger trick I don’t remember from Fellowship) Aragorn declares that the “rumor of the earth is dim and confused,” a mixture of emptiness for miles and the roiling, troubling stamping of hooves in the distance. He mentions that this land, which should have been populated by horses and men, was too empty, filled with “a silence that did not seem to be the quiet of peace.” Everyone is too tired, the stars are wrong, something is off. It’s a good introduction to this contemporary Rohan: too quiet, but also threatened by looming, impending chaos. There are cracks appearing in a place that should have been a refuge, the sense that something important has been altered or undermined.

Éomer and the Riders

Despite this unsettling introduction to Rohan, we get a heartening introduction to the Rohirrim themselves when Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas run into Éomer and his éored on the plains. Aragorn gives the Rohirrim their introduction:

They are proud and willful, but they are true-hearted, generous in both thought and deed; bold but not cruel; wise but unlearned, writing no books but singing many songs, after the manner of the children of Men before the Dark Years… They have long been friends of the people of Gondor, though they are not akin to them. It was forgotten years ago that Eorl the Young brought them out of the North, and their kinship is rather with the Bardings of Dale, and with the Beornings of the Wood.

I have always had a special place in my heart for the people of Rohan, and I think Tolkien did too. They are the most Anglo-Saxon-y people in a very Anglo-Saxon-y story. They are brave but moderate, at their foundation portrayed as a good, hearty people. Tolkien writes about them with that specific respect and reverence you see when hyper-literate people like Tolkien write about oral societies that didn’t write their stories down, when scholars write about warriors.

That said, Tolkien doesn’t overly romanticize them. He’s clearly very into the Rohirrim culture, but in its current manifestation it’s unquestionably flawed. If Boromir’s Gondor was a bit mired in its self-perception as the Savior of the West, Éomer’s Rohan is hampered by its isolationism:

“I serve only the Lord of the Mark, Théoden King son of Thengel,” answered Éomer. “We do not serve the power of the Black Land far away, but neither are we yet at open war with him; and if you are fleeing from him, then you had best leave this land. There is trouble now on all our borders, and we are threatened; but we desire only to be free, and to live as we have lived, keeping our own, and serving no foreign lord, good or evil.”

Tolkien manages to keep this from being too one-dimensional by immediately injecting some tension in the story. Éomer himself, when he gets the chance to talk to Aragorn & Co. alone, immediately admits his dislike of his people’s official stand. He also flagrantly disobeys orders on two separate occasions. He also claims that regardless of how things go, the old alliance with Gondor would stand. It’s a nice layer of nuance – not only does it give the Rohirrim a layer of immediate complexity, but it also injects the whole narrative of The Two Towers with more depth. This close to Isengard Saruman’s treason is a potent reality and the actuality of a two-front war is much more imminent than it ever was in The Fellowship of the Ring. It makes a lot of sense that the reactions to such a political climate would be mixed and fraught, and dumping Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli into the midst of this gives The Two Towers a new and interesting sense of momentum.

“The Doom of Choice”

Aragorn continues to be front and center in The Two Towers. Though he frets on a couple of occasions, he’s clearly still riding high on his decisiveness at the end of “The Departure of Boromir.” He quickly and effectively makes a couple of decisions as they travel – when the trail runs dry he insists the orcs will not make for the river, and when deciding whether to follow the Orcs through the night and risk missing a divergence in the trail, he decides to rest. It’s not terribly clear that he makes the correct decision in the second case. Legolas certainly thinks he doesn’t. But Aragorn is clearly getting better at living with his choices, accepting their consequences and moving forward. “Well, I have chosen,” he says in the aftermath. “So let us use the time as best we may!”

There’s a new confidence in Aragorn in “The Riders of Rohan” as he forges out as the head of his little Company and continues to make their decisions. He’s more regal than he’s ever been when he speaks to Éomer for the first time: not only does he declare his ancestry and show off Andúril but he’s increasingly insistent that Éomer choose a side in the wars to come. Poor Éomer hears Aragorn’s litany of recent bad news and asks him what doom he’s brought from the North.

“The doom of choice,” said Aragorn. “You may say this to Théoden son of Thengel: open war lies before him, with Sauron or against him. None may live as they have lived, and few shall keep what they call their own.”

More so than he ever did in Fellowship, Aragorn here feels like a leader. He’s not rash in his decision making but he’s more confident, less fraught with uncertainty. It’s been an interesting character arc to watch, and one that I hadn’t remembered very clearly. For Aragorn so far, being a leader has been about becoming comfortable with making hard choices. It’s something that comes out almost subconsciously – when imploring Éomer to take a stand in the war, Aragorn asks him to make a quick decision on at least three separate occasions.

Gimli and Legolas

Though less to the forefront than Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas also have a nice chapter in character development. This occurs largely through the contrast set up between the three characters.

Aragorn saw a shadow on the distant green, a dark swift-moving blur. He cast himself upon the ground and listened intently. But Legolas stood beside him, shading his bright elven-eyes with his long slender hand, and he saw not a shadow nor a blur, but the small figures of horsemen, many horsemen, and the glint of morning on the tips of their spears was like the twinkle of minute stars beyond the edge of mortal sight. Far behind them a dark smoke rose in thin curling threads. There was a silence in the empty fields, and Gimli could hear the air moving in the grass.

Aragorn is always trying hard and taking the lead. Legolas is effortlessly effective. And poor Gimli is at a serious disadvantage, but trying his best.

This is Legolas’s most “inhuman” chapter in the story so far – he sleeps with his eyes open when he needs to sleep at all, he never tires in their endless chase, his judgment is nearly impeccable throughout. At one point Aragorn uses all his sensory skills to determine that riders are approaching in the distance, and Legolas just casually notes that yes, there are, and “there are one-hundred and five. Yellow is their hair and bright are their spears. Their leader is very tall.” Aragorn, to his credit, manages to not be annoyed by this.

And then there’s poor Gimli. He’s hanging out with a heir-in-waiting Ranger and an elf who usually just wanders around singing at night, while Gimli desperately tries to recover his strength. And this is a really brutal endeavor – the three hunters cover over forty miles in their first day of travel and in the less than four days that elapsed before meeting the Riders they basically run 155 miles. It’s telling that Éomer is markedly more impressed by how far they traveled than the fact that Aragorn is the secret lost king of Gondor.

Through all of this, I found it really sweet that Legolas and Gimli’s friendship is cemented rather than strained by this. There’s no sense that Gimli resents Legolas for his literally superhuman endurance, and Legolas is always ready to back up Gimli without ever appearing condescending. When Gimli shows reticence to ride off on Rohirrim warhorse, Legolas just tells his buddy to hop on the back of his. And when Gimli threatens to murder Éomer for badmouthing Galadriel (!), Legolas is right there to back him up. I’ve always liked their relationship, but I’m finding myself more appreciative of it on this re-read.

Final Thoughts

- Speaking of the near-miss battle with the Rohirrim, I find it a genuinely funny scene:

“Let Gimli the Dwarf Glóin’s son warn you against foolish words. You speak evil of that which is fair beyond the reach of your thought, and only little wit can excuse you.”

Eómer’s eyes blazed and the Men of Rohan murmured angrily and closed in, advancing their spears. “I would cut of your head beard and all, Master Dwarf, if it stood but a little higher from the ground,” said Éomer.

“He stands not alone,” said Legolas, bending his bow and fitting an arrow with hands that moved quicker than sight. “You would die before your stroke fell.”

The escalation that happens in this scene manages to be both believable and ridiculous at the same time, and it’s really delightful to me. I like to imagine that Gimli is just flat-out exhausted from having run hundreds of miles in a few days and then he meets this dude riding around on a horse who insults Galadriel, and he is just done. - Let’s also take a moment to celebrate how great Éomer is. I’m interested to compare him to Faramir later on, because at this point they really remind me of each other. Éomer is having a rough time – he’s having to disobey his lord in order to do what he feels is right, he discovers from Aragorn that both Gandalf and Boromir, important allies in his fight ahead, have recently died. Some guy shows up in the middle of a field with a belligerent dwarf and elf and claims to be the lost heir of Gondor. Éomer really takes most of this in stride. Though he mentions that “the world has grown strange” and questions “how shall a man judge what to do in such times?” he also remains remarkably open-minded. He apologizes to Legolas and Gimli about his words on Lothlórien, claiming that “I spoke only as do all men in my land, and I would gladly learn better.” It’s humble and open-minded attitude that makes me think the world of Éomer and love him a little. So far he is a brave, kind guy who refrains from getting belligerent or defensive. I like him a lot.

- Contender for the most Tolkien-y of all Tolkien lines: “Halflings! But they are only a little people in old songs and children’s tales out of the North. Do we walk in legends or on the green earth in the daylight?”

“A man may do both,” said Aragorn. “For not we but those who come after will make the legends of our time.”

This is an early example of something that will become more and more prominent throughout The Two Towers, if I remember correctly: the awareness of the characters of their role in a continuing narrative. I’ll very likely have more to say on this later. - Prose Prize: The prose in this chapter is perfectly fine but Tolkien standards, but nothing really jumped out at me. I do like the three perceptions of the arriving Riders of Rohan, though, largely because it’s both evocative and does nice character development work for Legolas, Aragorn, and Gimli.

- See you in two weeks! We’ll see what’s been going on with poor Merry and Pippin as we have our first change in narrative perspective. Four chapters til Éowyn.

Art Credits: All movie stills are from Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, courtesy of New Line Cinema. All other art, in order of appearance, is from James Turner Mohan, Miruna-Lavinia, and Peter Xavier Price.