Image Comics have come a long way. Sure, the hell spawn and the bloody damned heroes have a charm of their own. But now we’ve got some sexy new comics to talk about. I wrote an entire prologue to Image’s evolution and these new titles last week, so let’s just get to it. Hold on to your feelings, for this will get real pretty.

Saga #1

“It’s a girl.”

Right off the bat, the word ‘saga’ hints at the gravitas of Norse mythology. The very sound of it conjures images of grand voyages, perilous quests and immortal prowess. It is no incident that such a word could be chosen to encompass the narrative of an epic space opera. Surely, this magnificent tale will begin with grandiose atmosphere and heroic ambience. It all starts in the planet Cleave, with the birth of a child.

Well, I’d say it rather does, to some extent. Regardless of the charming tone of events, we might now have our ‘Sigurd’ equivalent to this saga. Parallel to these events, we have an in extrema res narration from an unknown character. At this early stage, the reader could reasonably think it’s a new mum’s recollection on past events. Speaking of whom, meet Alana; she’s a woman belonging to a species of winged people. She’s fierce and saucy. As for the dad, meet Marko, a man belonging to a species of horned people. He can be quite a softie. These are our protagonists, and they’re pretty cool people. They’re also our first step into a world of guns and magic.

Soon enough, the side narration turns out to be the baby’s perspective, as an adult. This person, more mature and a bit jaded, seems to struggle with not getting ahead of herself. This narrative device works neatly to foreshadow and to lead the reader’s expectations in one direction or another. There’s only so much she can tell us, however; the events unfolding will do the rest. Seeing Marko severing the umbilical cord with his teeth should ring with Tristram Shandy-ish echoes. By this association, these events could build up to her role, which could end up being deliberately underwhelming as a subversion of the trope. On the other hand, the trope could be played straight, as she has inherited a sword by sole fact of being born during wartime.

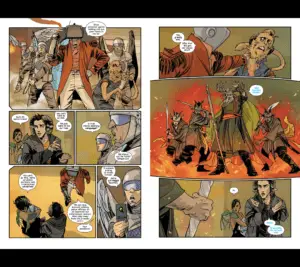

The post-giving birth banter between Alana and Marko hints at deep cultural differences between their races. This is a generous way to put it, though. Turns out, their species have long been at war with one another. The complications of these circumstances become obvious as a group of TV-headed operatives violently bust in. An ally of Marko seems to have sold them out. Not to worry, as a group of horned fellows join the party, and shit goes down as they rain violence by magic on the robots. It seems that this birth is quite the event. The baby’s narration fills us further in about the nuances to this war.

The winged people are natives to the planet Landfall, which has only one moon, Wreath. This is where the horned people hail from, pejoratively called ‘moonies’. The latter speak a language of their own, loosely based on Latin, and are capable of wielding magic. The war’s gone on for too long for anybody to remember how it began. It has also expanded throughout the galaxy, as multiple planets have picked a side. This includes the Robots from the Robot Kingdom. They have allied themselves with the Landfallians against the people of Wreath.

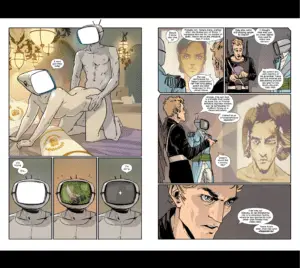

Several important personages have emerged from this history. Meet Prince Robot IV; he’s a shell-shocked war veteran and kind of a dick. After a spoiled love-making session, he receives an inconvenient visit from a Landfallian Special Agent. He has a briefing on a new mission for the Prince, who is reluctant to go. Through this briefing, we learn more about Alana and Marko. She was a guard in the prison where Marko was held as war prisoner. For reasons and with means unknown, the two manage to escape the prison together. While examining the footage, Alana is already visibly preggy, but the Agent discards the possibility of a rape. Much to the surprise of Prince Robot IV, he concludes that it was actually a union of love. Apparently, there are dangerous implications to this event. Alana and Marko must be taken out, and their child also suitably dealt with.

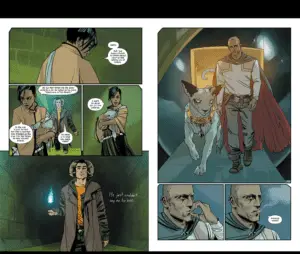

Of-fucking-course we’re getting some heavy Romeo and Juliet vibes already. Unlike those two dumb kids, though, Alana and Marko seem at least moderately competent. They escape the standoff through the sewers while arguing like a married couple, as you do. The guy who sold them out, now dead, had given Marko a map beforehand. This little asset seems sloppy, but they nevertheless have a destination: the Rocketship Forest. However, they are unaware that external forces will soon be on their trail. One of these persons of interest is a man called The Will.

The Will is a freelancer and a constant smoker, like yours truly. He’s also reputable, dangerous and resourceful, unlike yours truly. He travels along with Lying Cat: a big hairless cat that can tell when you’re lying. She’ll literally say it out loud, much to the embarassment of all living things. This beautiful duo has been charged by a woman from Wreath to also take out Marko and Alana. However, he is to bring their child back to her, unharmed. We don’t know what her intentions may be, but she is too smartly attired to be well-meaning. So far, this makes two parties determined to hunt our heroes down, especially their kid. This sense of urgency is already super effective. The play on cliches is not getting old at all; it’s actually even refreshed.

Back to the recent-parents, they wade through a creepy forest at night. They haven’t made it yet to the Rocketship Forest, though Marko’s wary about strange ethereal beings lurking in the forest. His scepticism about actual ships that grow on trees contrasts with Alana’s scepticism about the Horrors that haunt the woods. Curiously, such contrasting disbelief about both elements of fantasy actually endows this universe with greater depth. This selective scepticism, the linguistic barries (however basic) and the seemingly irreconciliable history between both species starts speaking miles about the galaxy itself. However, as a cruel howl of the circumstances echoing back at them, fiery battle has broken out in the forest.

Alana feels discouraged about their odds to escape this war. Regardless of their drive, they cannot escape the present. With or without targets on their back, war will own them as it has for countless planets. Marko steps up and comforts her by taking on a greater resolve towards success. Though the external circumstances will be adverse, the couple are resolute and nearing their destination. Such a moment can only be crowned by the naming of their daughter: Hazel. Her parents will show her the universe. From ‘two against the world’, the motif has transformed into ‘our child deserves better’.

As for Hazel herself, she says she won’t grow to become a character of relevance. Already this comic has adopted and subverted literary several conventions, so it is actually plausible. However, what indeed can we consider ordinary in this universe that’s just been opened to us? Let alone the fact that we’re punkass humans in comparison to Alana, Marko and especially the Lying Cat (She’s the best). Such palette of graphic and narrative colours don’t leave much room for half tints and pusilanimity. Will Hazel, our Sigurd in this instance, turn out to speak true? Only time, and the trials of her mummy and her daddy, will tell.

And so, ends the first issue of Saga. Now moving on to…

The Wicked + The Divine #1

“I Want Everything You Have”

English television has given us a few series about adolescents. Skins and Misfits (which some would say is really the former with superpowers) quickly come to mind. These narratives feature an age group functioning in a social context, exploiting it and often being victimised by it also. We’ve all been there, and we know it can be a volatile age to live. In fiction, it can become especially imbedded with a tint of fatalism. It becomes a coin toss, a choice between life and death. The title of this comic series already expresses such stark duality. But what could be the extent of these dichotomies? Could such a steep price not affect the way the characters experience their lives?

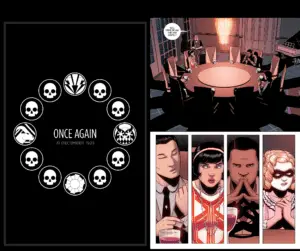

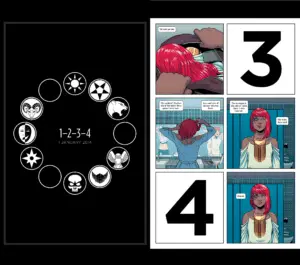

We start off on December 31, 1923. We first get a black page featuring a circle outlined by twelve effigies. Four of these show distinctive icons, whereas the rest only show skulls; semiotic doom. The scenery is a secretive gathering at a round table: four strange young personages are seated, and a strange old woman is in their midst. There are lots of empty seats hinting at disturbing implications. The youths suitably appear to experience varying facets of apprehension. It’s dangerously looking like a sort of suicide pact as the old woman walks away with a rueful expression. The four agree to get to it, and start a countdown out loud, with their hands stretched, ready to snap their fingers. At the final click, the house explodes into flames. Only the old woman remains.

Fast forward to January 1, 2014 for another black page with a new circle. We see nine distinctive symbols and three hollow circles. Minds could be racing about what this means, but it’s pretty succint. We got a clean slate and no casualties yet. It’s a lovely day in South London. We follow a girl who reminds me of Antonia Thomas, and her name is Laura Wilson. She is excited, for something grand is occurring that day, but she needs to prepare for it. We’ve all been there, haven’t we? She walks into a bathroom and applies artful makeup, and dons a long-haired red wig. Other girls are doing likewise. This scene is no strange thing to people who cosplay. Nuance and detail are important to incarnate the character. She finds the image on the mirror pleasing to her purpose.

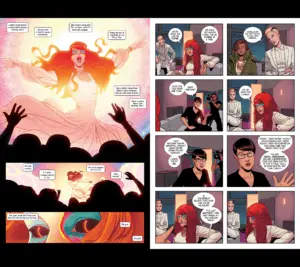

But even if the result is beautifully achieved, it’s not enough. There’s ‘something’ Laura can’t hope to replicate: something she wishes she could have. It’s the ‘something’ that hundreds have come to see that day. Amaterasu, the girl who became the Japanese Sun Goddess is giving a show. She’s a pop star. Real soon, we can observe this worshipping of the celebrity as a reprisal of the cult to a deity. After all, are musicians not the Gods of our age? We anoint ourselves in their grace by consuming their products. We adore and praise as they take the stage. We partake of the communion by obsessing next to others who too enhance their lives with their songs.

This would all be no more than a pretty allegory if not for one thing: she’s literally a Goddess. The show proper, as narrated by Laura, has an indomitable physical effect on the attending fans. One such admirer even climaxes in his pants from the ecstasy of her performance. In this instance, we’ll benefit from distancing ourselves from the modernised, Western conception of deity. Looking past the collective adoration, we observe divinity by what the deity proper is doing. I can find no better way to describe it than by one single word: immanence. Amaterasu is manifesting divinity itself into the physical world; she’s raining love on her fans. As an effect of this, Laura, among others, passes out.

Who shall wake up our heroine from this rapture-induced faint? Why, a girl who appears to incarnate the stylish, furiously dapper side of David Bowie and Annie Lennox, of course. Meet a Beatles-born child who lights her cigarettes by snapping her fingers, as I wish I could. Her name is Luci, which is short for Lucifer, and she loves drawing attention. As expected from one who incarnates the Prince of Lies, she speaks pretty elusive and cryptically. Even Laura finds it kind of annoying after a while. Make no mistake, though, Lucifer is way cooler than she is devious. She even gets Laura to a fancy loungey backstage-y place where some Gods hang out. Hanging with the Devil seems to have its perks.

At present, only Amaterasu and another God are in the lounge. The latter is Sakhmet, Egyptian Goddess of War and Dance, often depicted as a lioness. She’s very cat-like, and at times, mindlessly hedonistic. For the time being, she’s just busy looking bored and uncaring, like cats do. On the other end of the couch, Amaterasu is being interviewed by a cynical journalist. This one appears as much as a caricature as the Gods themselves. Meet Cassandra, a person on the stiffest end of scepticism. It seems she doesn’t aim at interviewing Amaterasu so much as trying to oust her as a fraud. Through her scrutiny, we learn a bit about what’s going on. Once every century, a bunch of Gods incarnate several youths, who live as deities for two years. Then they die, or at least it’s hinted that they die. This event is called The Recurrence.

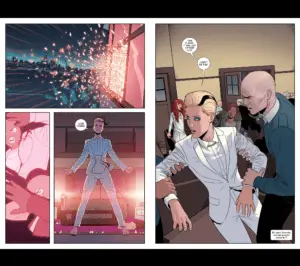

As it is, Cassandra is not impressed and thinks this all a publicity stunt. Sakhmet constantly chasing a red dot, as your cat does, doesn’t help things. However, this bit of slapstick instantly turns dire as the red dot turns out to be a laser scope from a rifle. Outside, a party of Christian fanatics are about to rain bullets on all Gods in the lounge, including non-Gods Laura and Cassandra. Luci intervenes before this reprisal of pre-Christian religions’ subdual takes place with a vengeance. With a snap of her fingers, the assholes’ heads explode. This exhibition of power saves a couple of lives. It also humbles Cassandra a bit. Everybody wins.

Next day, there’s a court session against Lucifer for the deaths of these douchebags. Naturally, Luci is not very cooperative. After all, her actions were justified, though unlawful. Furthermore, she is Lucifer, a God canonised by signification and cultural impact rather than inherent status. Thusly, she talks with marvellous sass and taunts the judge by teasing a snap of her fingers. When she does snap her fingers, though, the judge’s head explodes. For any witness at the scene, Lucifer, Patriarch of Evil, is a God drunk on her own power. But no, she appears genuinely and utterly shocked as her sass falls apart. She’s held guilty and only Laura seems to believe her innocence for this particular head-exploding. Is she as much a liar as the Devil, or has she been framed?

We’ll find out next issue…

The first part of this comic series is shorter than Saga’s. However, there’s a metatextual resource to observe at the end of the issue. It’s a letter written by Kieron Gillen to the reader with the intent of making a point. It could be easy to relate the current story to their previous work on Phonogram. Both narratives share plenty of characteristics, namely fantasy and pop culture. However, the devil is in the details, as is a world of nuance. Phonogram featured fantasy occurring in our world; it created a sense of magic pulsating behind the walls of the commonplace. The Wicked + the Divine, on the other hand, is an entirely new world, divorced from the very notion that this could be occurring, even if the rules of reality were severely challenged and bent.

The peculiar thing about WicDiv is that it dismisses the importance of the pop culture’s corpus we know as a link to our reality. Yet, at the same time, it upholds its importance to make this new universe an apprehensible experience. It seems like our pop culture icons are fixed points in time and space. I’d summarise this with the following personal axiom: “One cannot incarnate our Gods of old while forgoing our modern Gods”. Can anybody imagine a world where the Archfiend can openly mock the law, and physical rapture can be experienced at the cost of a ticket without the existence of David Bowie? I think not.

Thus we end this week’s little double feature on Saga and The Wicked + The Divine. The genre is most definitely fantasy, but there’s something else they share in common: intertextuality. Vaughan and Staples for Saga, and Gillen + McKelvie for WicDiv, have all fed from the diegetic universe of foundational myths. As a consequence, we get new takes on previously told stories towards untold, unexpected approaches. Nothing is new, but at the same time, everything is new.

Published by Image Comics

The Wicked + The Divine: Written by Kieron Gillen, Illustrated by Jamie McKelvie

Saga: Written by Brian K. Vaughn, Illustrated by Fiona Stables