Are you a werewolf? Are you perhaps ultimate werewolf or more of a “one night only” kind of gal? Maybe you’ve been in the mafia? Well, then you may have played a game similar to Salem 1692, the second game in indie game company (and we mean indie, they have a total staff of two) Façade Games. Rather than simply re-skin the “deduct and accuse” formula that has, admittedly, been very successful, Façade instead takes the whole thing back to their roots, to the very first social game of accusation and deduction, murder and distrust that was ever played: The Salem Witch Trials.

What’s In The Box?

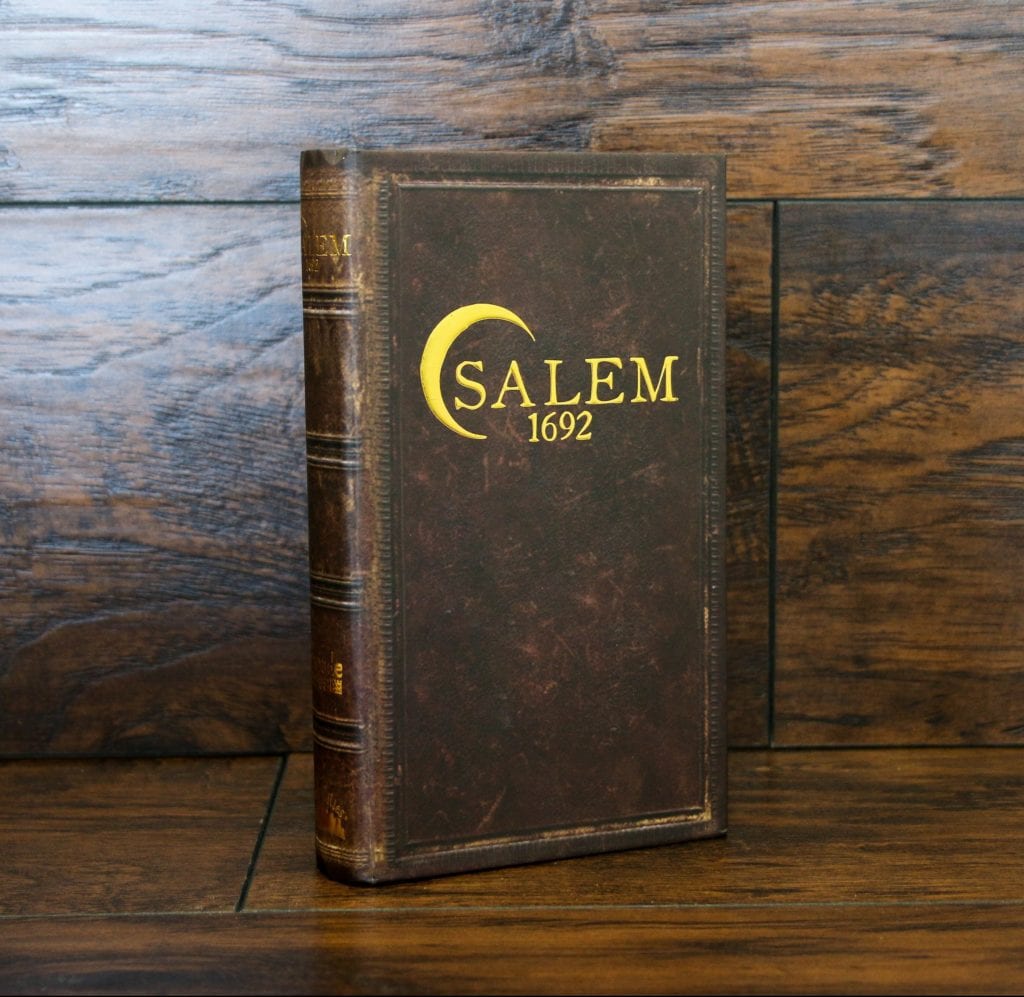

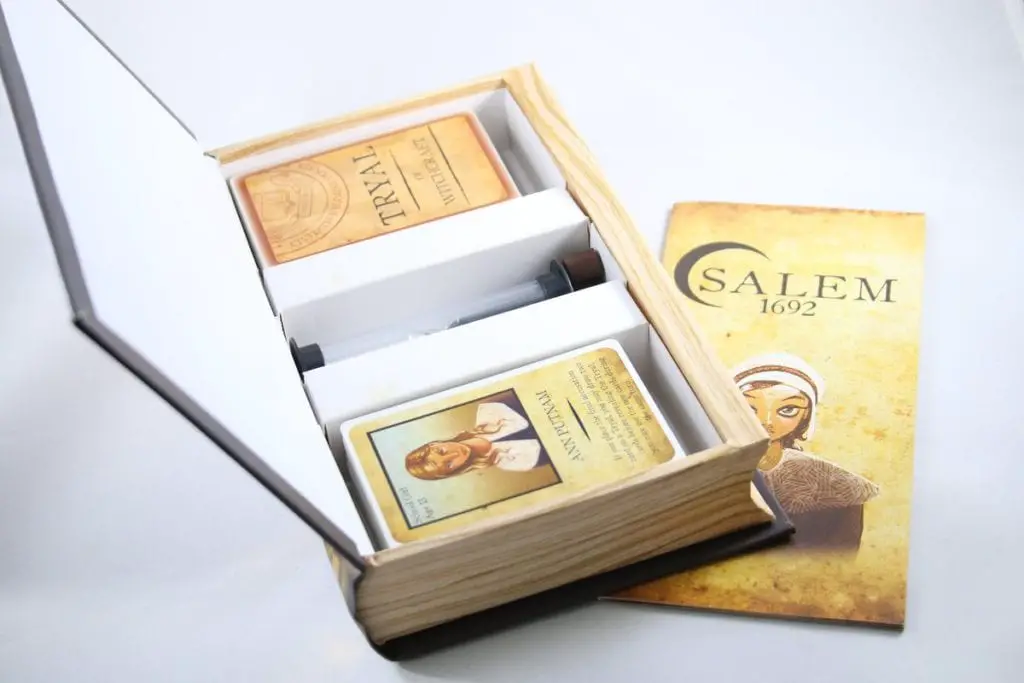

Salem is the second edition of Façade’s debut game, and officially the second in their Dark Cities series after Tortuga 1667 . It comes in a faux dark leather book that’s been beaten, scratched, and warped by (seemingly) 326 years. Façade’s choice to do the title in gold foil makes the small game pop whether its on a table or hiding among your reading material. It’s packed efficiently and reflects a high level care and planning on the part of the designers. The games cards and booklet are beautiful as well, glossy but with an aged look you’d expect for things ostensibly 400 years old.

The artwork, done by concept artist Sarah Keele, is highly stylized, without being cartoon-y, and pops off of each card. The character portraits are especially good, oozing personality without leaning too heavily on stereotypes or misconceptions. There’s also a little hourglass, filled with black sand of course, and a tiny little wooden gavel token that is mostly just a feelie but adds some extra physicality to the game.

How’s It Played?

In Salem: 1692, you aren’t just any random Puritan. Instead, you take on the role of a historic resident of Salem, Massachusetts at the time of the famous witch trials like the vindictive Abigail Williams, witch hunter Cotton Mather, and the man himself, Giles “I’ll Show You Stones” Corey. You might also think back to high school English and The Crucible, as most of the cast is represented here in some form or another. Each resident has their own special “power” that reflects something about them. Some are as simple as George Burroughs requiring more accusations than normal to lose a trial, reflecting his status as a minister; while others are more complex, like John Proctor’s ability to take items from the dead just as he would accept pawned goods as payment in his tavern. These “powers” are huge help in the game, and make your “identity” in the game more than merely cosmetic.

At the beginning, the Town Crier is selected. Usually this is the most experienced player of Salem who will direct the game while they play. If nobody has played before, as in my first game, then you use a moderator who fulfills a similar role, but is not involved in the game. The players are each dealt a number of Tryal (not a typo, a fun bit of flavor to fit with the time) cards that determine their roles in the game. This is where the witches find out if they are witches, as well as the constable. The game ends when either the Witches have killed or converted the whole village, or when the constable has revealed all the witches lurking among the populace. These identities are secret, and only the players know if they’re guilty or innocent until the accusations start to fly.

The game progresses similarly to its brethren in the deduction game genre, though there are some twists in the formula that help it stand out. For one, each player’s Tryal cards must be selected blindly, meaning that a well-intentioned villager could waste their accusations on someone before finding out they were a witch, simply by random chance.

The constable role is another variation on the “sheriff” type roles in similar games. Here they retain their ability to protect villagers from witches , but the role of constable can change hands (sometimes more than once), and the constable can even BE a witch. And take my word for it, you DON’T want a constable witch.

There’s also special color coded cards that affect the game in different ways. They’re drawn at the start of each turn. Green cards are sort of like “instants,” single use cards that affect other players in the short term. Examples of green cards are “Arson,” which lets you discard another player’s hand, and “Alibi,” which lets you remove another player’s accusations. Blue cards are similar to an enchantment, such as the “Asylum” card that protects a villager from witches in the night. A particularly fun example of these is the “Matchmaker” cards, which link two players in such a way that if one dies, they both die.

Red cards are where the “trial” part of the game comes into play. These are the accusations that villagers can throw at each other to ferret out the devils in their midst. Most of these are worth one or two, but some go up to four in one go. Once a villager gets seven accusations they must flip a Tryal card (except for George Borroughs, who needs eight). If they’re a witch then they die. If they run out of Tryal cards, they die.

The scariest cards in the game are the black cards, played the minute they appear: “Night”, and “Conspiracy.” “Night” is the traditional “baddies come out to do murder” portion of the game. The “Conspiracy” card forces all players to pass one Tryal card to the left. This is how the witch coven grows, as the minute you get a “witch” card, you become a witch (which is how AARP works in real life). And even if you lose your witch card, you remain a witch. The special “Black Cat” card comes in to play during “Conspiracy” as well. Initially gifted by the witches at the start of the game, when it serves to handicap another villager or throw the hunters off the witches’ scent.

The game goes as quickly or slowly as the players let it, and depends heavily on the cunning of the witches and the deduction skills of the players, but it rarely will last more than a half hour, forty minutes tops.

Salem: 1692 is a fantastic middle ground between the rapid pace of the One Night family of games and the methodical plodding of Ultimate Werewolf and the like. It’s refreshing to see a game stand out not with the use of flashy mechanics or weird gimmicks, but with a little bit of grounding in history instead. The flavor of the game is superb, mixing more dramatic ideas from The Crucible (how could it not) with things rooted in actual horrors that went on in Salem. Things like the “Matchmaker” card, the methods of accusation, and even the “power” of each character goes a long way towards immersing you into a distinct time and place.

It is also the first game I’ve reviewed for The Fandomentals that could be considered educational, and it even has deeper history in the back to illustrate how much work was put into researching the game.

The Verdict

For a company as small as Façade, the craftsmanship here is superb and very much a labor of love for designers Holly and Trevor Hancock. Little things like possible rules conflicts, adaptations for big groups and new players, and even rules for making the game last longer or become even more difficult. While it may not be different enough to sway those who like the more rapid or supernatural deduction games, I think that this is a worthy addition to any shelf for fans of the genre, and a perfect game for Halloween.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Salem: 1692, as well as the other games in the Dark Cities series, can be bought at Façade’s website, as well as at your local game store, for about $25. Keep an eye here on The Fandomentals for more news and reviews on board games and the latest from Façade.