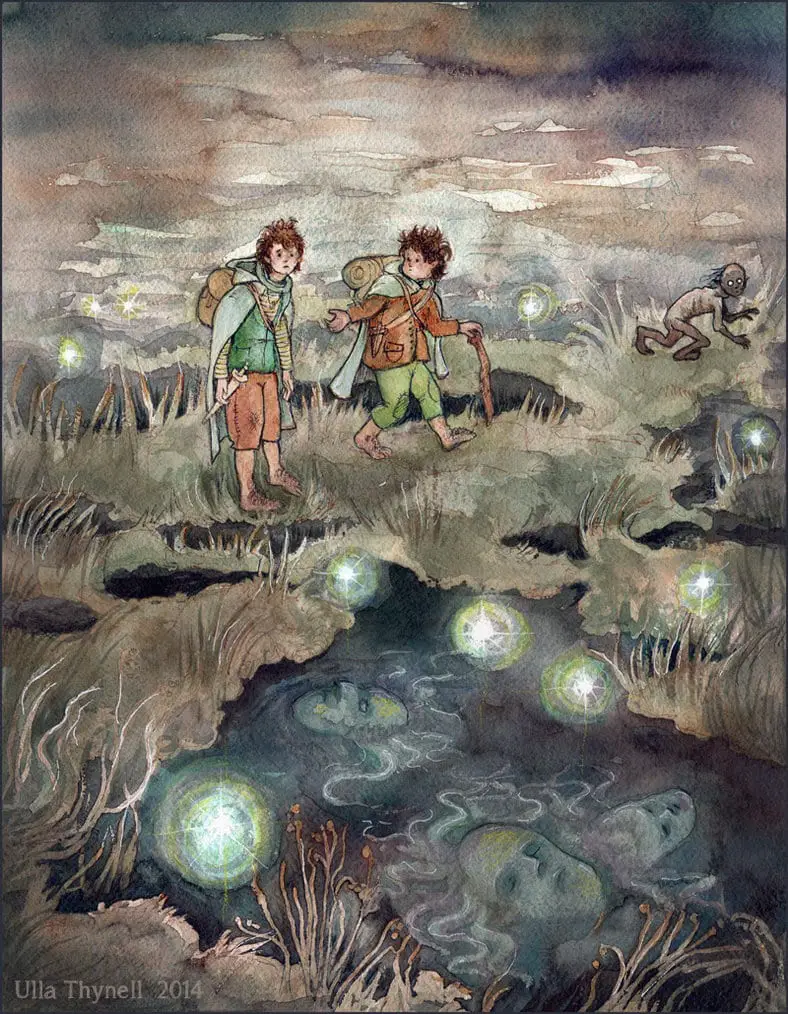

There’s a sense of motion and movement in “The Passage of the Marshes” that’s quiet, persistent, and devastating. It starts early, through one of Tolkien’s favorite techniques: the transition in landscape (chapter 2 of Book III featured one as well). As Frodo, Sam, and Gollum move from Emyn Muil into the Dead Marshes, the mood noticeably darkens and chills. Sharp stones and shallow pools get exchanged for greasy bogs, rotting moss, foreboding lights. In a lesser fantasy novel, the marshes would essentially function as a level to be beaten. See some new scenery, fight some monsters, make it out to the other side and a well-deserved respite. But Frodo & Company don’t fight any monsters. They make it out to the other side, and things only get worse.

It’s an interesting narrative choice on Tolkien’s part. The story gets very dark, very quickly. Frodo is exhausted and fraying at the edges. Sméagol is flickering in and out of existence alongside Gollum. Sam is frustrated, anxious, and cruel. There are repeated moments, throughout the chapter, in which the quest is treated (explicitly or implicitly) as a suicide mission. There’s an odd sensation that the hobbits are moving very slowly – first picking their way through rocks and cliffs, then picking their way through bogs and fens – but also inexorably tumbling forward to a destination that feels immutable and fixed. And “The Passage of the Marshes” underlines both the isolation and connectivity of these characters, how internal, near-unshareable problems become buffeted about based on how these characters interact with each other.

Sam and Gollum

Growing up, Sam Gamgee was my favorite character by far in The Lord of the Rings. I essentially thought of him as the protagonist of the series. I don’t think that’s necessarily a wrong interpretation, but it’s been interesting diving into Book IV and seeing him in a different light. Fellowship was much lighter on Sam than I remembered, and I was struck in this chapter – our first fully from Sam’s perspective, if I’m remembering correctly – at how unkind he can be. Sam spends the majority of the chapter both distrustful of and disgusted by Gollum, with a slight undercurrent of pity throughout. He’s operating under the assumption that Gollum will eat them at the first chance he gets (which, yikes, Sam) and at various points he glares at Gollum, pokes him, and fantasizes about murdering him.

It’s easy to be mad at Sam for this, particularly since we know where all of this is going and we get to see Gollum at his most Sméagol-like moments. He opens the chapter frolicking around in a river and “greatly delighted” at the feel of running water on his feet. He leads them rather faithfully through the Dead Marshes, something Frodo and Sam would have been unlikely to complete on their own. For most of the chapter he is scared and starving. And when both Sam and Frodo fall asleep on guard duty he’s perfectly well-behaved. He even seems to wait around for Sam to wake up in order to tell him that he’s off to gather some food (his “Be back soon!” really made me laugh).

But at the same time, Sam also has legitimate cause to be concerned. Gollum, though I have all the pity in the world for him, is also dangerous and unstable, and kept in close proximity (though not close enough) to the thing that is driving him mad. He’s muttering references to riddles he told fifty years ago. When he doesn’t murder Frodo and Sam in the night he literally says “Trust Sméagol now? Very, very good.” And in the Gollum-Sméagol dialogue at the chapter’s end, it becomes obvious that even at his best, Sméagol has only a flimsy barrier erected against the idea of taking the Ring for himself (though he is, throughout, genuinely upset about the idea of hurting Frodo).

That’s not to say that Sam’s behavior is excusable, of course. I think that it is (in part) to blame for Gollum / Sméagol’s eventual decisions and actions. But it’s also perfectly in character for Sam, and it’s the flip side of the dedication and loyalty that he patiently and consistently shows to Frodo. His hatred from Gollum stems from fear, and his fear stems from love. It’s not a great quality in this context, and it’s interesting to speculate about what may have happened had Sam followed Frodo’s model of dealing with Sméagol with an unrelenting kindness and compassion. But it’s also a fitting quality, and goes a long way in making Sam a vibrant, interesting character.

Sam and Frodo

Sam’s behavior towards Gollum, of course, stems from his behavior and feelings towards Frodo. Tolkien is good at seeding the depth of their relationship, even in a chapter (with one key exception we’ll get to in a minute) where they don’t speak much, and mostly of logistical matters. When Sam falls asleep on guard duty he wakes up furious with himself. “Various reproachful names for himself came to Sam’s mind, drawn from the Gaffer’s large paternal word-hoard.” When Frodo wakes up afterwards, without prompting, he urges Sam not to “think of your Gaffer’s hard names.” It’s a nice moment, uncommented-upon, that shows how much these characters care for each other and understand each other.

And that relationship is underlined by the fact that Frodo increasingly seems to be sort of fading away. His trip through the marshes is a difficult one:

He was now beginning to feel it as an actual weight dragging him earthwards. But far more he was troubled by the Eye: so he called it to himself. It was that more than the drag of the Ring that made him cower and stoop as he walked. The Eye: the horrible growing sense of a hostile will that strove with great power to pierce all shadows of cloud, and earth, and flesh, and to see you: to pin you under its deadly gaze, naked, immovable. So thin, so frail and so thin, the veils were become that still warded it off. Frodo knew just where the present habitation and heart of that will now was: as certainly as a man can tell the direction of the sun with his eyes shut.

The thin veil between safety and catastrophe only serves to draw Frodo closer in parallel to Sméagol. It’s an odd sort of struggle for Frodo. On one level, it feels visceral and almost violent: there’s a “hostile will,” a “great power,” a “deadly gaze.” There’s piercing and pinning. But it’s also nearly all internal and silent. Whereas Book III was a near-constant sprinting around to deal with tangible threats, Book IV is deeply, deeply internalized.

And Sam is aware of this. He notes that while Frodo appeared exhausted, “he said nothing, indeed he hardly spoke at all; and he did not complain, but he walked like one who carries a load, the weight of which is ever increasing.” He never loses his temper with Gollum, just speaks to him with a kind, yet abstract sort of compassion. And he seems mesmerized by the lights in the Dead Marshes. His description of the faces in the water, delivered in a “dreamlike” tone, sounds almost like a poem: “They lie in all the pools, pale faces, deep deep under the dark water. I saw them: grim faces and evil, and noble faces and sad. Many faces proud and fair, and weeds in their silver hair.” There’s a singsong lilt to it, that once again ties Frodo to Gollum, who opened the chapter with a “sort of song.”

It’s a difficult chapter for Frodo. But also for Sam: it’s hard for me not to see his behavior towards Gollum as a kind of projection, an overly-aggressive and sometimes belligerent protection that he undertakes largely because he can’t actually do anything to help Frodo or alleviate his burden.

The Question of Hope

“I don’t know how long we shall take to – to finish,” said Frodo. “We were miserably delayed in the hills. But Samwise Gamgee, my dear hobbit – indeed, Sam, my dearest hobbit, friend of friends – I do not think we need give through to what comes after that. To do the job, as you put it – what hope is there that we ever shall? And if we do, who knows what will come of that? If the One goes into the Fire, and we are at hand? I ask you, Sam, are we ever likely to need bread again? I think not. If we can nurse our limbs to bring us to Mount Doom, that is all we can do. More than I can, I begin to feel.”

Sam nodded silently. He took his master’s hand and bent over it. He did not kiss it, though his tears fell upon it. Then he turned away, drew his sleeve over his nose, and got up, and stamped about, trying to whistle.

It’s hard for me to explain how much I like this passage. On first reading, it’s just brutally sad. Frodo assumes he won’t survive the mission, and Sam can’t even bring himself to fight the idea. There’s a deep current of determinism underlying it. Frodo and Sam are destined for Mount Doom, they’re being pulled there. Their choices about that fate seem to only change whether they die before or right after they get there. It seems bleak. But on a second read-through, there is a real undercurrent of hope here – or if not hope, at least love. Frodo’s assessment of the situation, honestly, is not a bad one. A trip to a giant fire mountain in the middle of a death plain surveyed by an unceasing malicious will searching for something you’ve got in your pocket does not really carry the convincing promise of a return trip.

But there’s some hope to be had in the fact that Frodo – who is so silent about his thoughts for most of the chapter – shares this with Sam. And there’s some hope in the fact that Sam doesn’t yell at him, or get angry with him, but simply sits and listens. There’s a solidarity and honesty in that moment where they sit and hold hands that I think is really human and beautiful.

In fact, it really reminds me of a kind of inverse or echo of a scene between Frodo and Sam all the way back in A Shortcut to Mushrooms. Frodo, doubtful of his mission and fearful of his friends being hurt, asks Sam if he wants to come along. Sam does, of course, and despite his misgivings Frodo doesn’t try to talk him out of it. Here, of course, things are a bit darker. But there’s still a foundation of understanding here that is so touching to me. Frodo didn’t try to talk Sam out of coming in a misguided attempt at self-sacrifice. And here Sam doesn’t try to make promises that he cannot keep, or force-feed Frodo some optimism from a place of greater comfort and safety. Instead they just listen to each other, and be with each other. It comes off a very dark moment in the series – when Frodo explicitly describes his quest as a suicide mission – but it’s a moment of genuine beauty, I think. It’s small, but it counts for so much.

The Question of Fear

Gollum is the flip side of the coin: he’s dealing with similar levels of despair, but he doesn’t have a Sam to take his hand. Frodo deals with the threat of despair with a quiet acceptance. He acknowledges it, and moves on and does what he can. Gollum, though, has gone through too much at this point – more than anyone else in the little company, he knows the visceral reality of what they’re facing. For him, every threat is a potential catastrophe. He fears the sun, the moon, the wraiths that fly overhead. The poor guy falls into a full-fledged panic attack when a Black Rider flies overhead. “Wraiths,” he wailed. “Wraiths on wings! The Precious is their master. They see everything, everything. Nothing can hide from them. Curse the White Face! And they tell Him everything. He sees, he knows. Ah, gollum, gollum, gollum!”

And when Sméagol and Gollum speak to each other near the chapter’s end, it quickly slides from a debate about ethics to a debate about fear. Sméagol starts by insisting that he had made a promise to Frodo. And it’s interesting that Gollum makes very little headway in the debate until “He” – presumably Sauron, or perhaps some lieutenant to whom Gollum-torture was delegated – is introduced into the conversation. Then, it quickly becomes an issue of survival, in which Sméagol simply panics that whatever he does he’ll wind up captured or dead, by servants of Mordor or by hobbits. It’s a hard scene to read: nearly everything about Sméagol / Gollum is difficult to read as soon as the first Black Rider flies overhead. He’s absolutely petrified.

And this suggests one final point about Gollum and Sméagol. I get the impression that most takes on his story are filtered through Frodo and Sam. Frodo, in his gentleness and kindness, nearly brings Sméagol back. Sam, in his distrust and dislike, gives the edge to Gollum. I think this is true, to a certain extent. But I also think that so much of Sméagol’s story comes down to the pervasive and destructive effects of fear on a person.

Even if Sam were as kind to him as Frodo, or kinder, I’m not sure that Sméagol could have handled the psychologic effects of having to walk back into the place that’s caused him so much pain and fear. It doesn’t work as a direct analogy, but it’s hard for me not to pick up Frodo’s use of the veil imagery. Frodo is fraying because that veil is getting thin; Sméagol has seen what’s behind the veil and is constantly reminded of it. This isn’t, of course, to say that the bonds between these characters don’t matter (that’s deeply untrue in The Lord of the Rings). But like so many other characters, Sméagol’s struggle has a component that’s resolutely internal.

Final Comments

- So far, true to form, I’ve been enjoying Book IV more than Book III. It is dark, though. There’s a sense of inevitability and doom that hangs over everything, even so early on.

- It’s been interesting to keep an eye on how Sméagol/Gollum is referenced. Whereas “The Taming of Sméagol” trended towards Sméagol as the dominant name, in “The Passage of the Marshes” he’s nearly always Gollum (largely due, presumably, to the fact that we’re in Sam’s point of view). He refers to himself once as “I,” referring to a time was he was young, “before the Precious came.” It makes me wonder how much of his pre-Ring past Gollum/Sméagol remembers, and how he feels about it.

- I respect Tolkien’s distaste for allegory too much to really dive into it, but it’s very hard for me to not read Sméagol and Frodo’s struggles (and on occasion the Ring in general) through the lens of mental illness.

- It’s both funny and concerning to me how bad Frodo and Sam are at keeping watch. It feels realistic to me – they are pulling long marches without training for this sort of thing – but it’s also funny how many times in the course of a single chapter they set up a watch schedule and then both promptly fall fast asleep for like ten hours.

- I am a fan of the phrase “paternal word-hoard” for Sam’s collection of self-depricatory curses.

- Also a fan of the lights in the Dead Marshes and how they wink out suddenly when the Black Rider arrives overhead. How Peter Jackson managed to not film this sequence is a question for which I will never find a satisfactory answer.

- And finally, also a fan of the description of Frodo and Sam as “little squeaking ghosts that wandered among the ash heaps of the Dark Lord.”

- Gollum’s description of his fear of the Sun – “You are not wise to be glad of the Yellow Face,” said Gollum. “It shows you up” – is DEEPLY ominous to me for reasons I don’t really understand.

- I liked that the description of the wasteland before the northern edge of Ephel Duath sort of parallel’s the description of the devastation around Isengard after the Ent attack (but on vastly different scales).

- Prose Prize: “Presently it grew altogether dark; the air itself seemed black and heavy to breathe. When lights appeared, Sam rubbed his eyes: he thought his head was going queer. He first saw one with the corner of his left eye, a wisp of pale sheen that faded away; but others appeared soon after: some like dimly shining smoke, some like misty flames flickering slowly above unseen candles; here and there they twisted like ghostly sheets unfurled by hidden hands.”

- Contemporary to this chapter: … Pretty much all of Book III? As Frodo, Sam, and Gollum approached the marshes, the Entmoot was beginning in Fangorn and Éomer was meeting Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli. As they crossed the marshes and approached the wasteland before Mordor, Gandalf made his big (re)entrance, everyone took a quick trip to Meduseld, the good guys came out on top at Helm’s Deep, and Ents totally trashed Isengard. No wonder so many Black Riders were flying overhead.

Art credits: The cover image is courtesy of Ted Nasmith. All other images, in order of appearance, are courtesy of Chris Reach, Miruna Lavinia, Dovilė Tarutytė, and Ulla Thynell.