At first glance, “The Voice of Saruman” can feel a bit anti-climactic. It’s a showdown between two wizards, but only after one of them has been effectively defeated. Saruman’s central power – a captivating, hypnotizing voice that convinces even when the words themselves are indifferently convincing – is tough to translate to the page. There’s very little suspense, and it never seems terribly likely that Saruman is going to win any kind of victory.

Because, honestly? Saruman seems pitiful. He’s trapped in a tower with a minion he despises. His home is a ramshackle swamp. His voice – touted by Gandalf as one of the most dangerous things in Middle Earth – is only marginally effective against the crowd outside. He is bitter, petty, and seems unable to accept the reality of his defeat. It’s hard to square this with the fact that Saruman is one of the most powerful forces in Middle-earth.

But “The Voice of Saruman” is also a fascinating chapter, because it reads as the culmination of a story that’s been running quietly in the background, parallel to The Lord of the Rings in both sequence and theme. Saruman is a distorted mirror of Gandalf, of course. But he’s also a distortion of, or a warning to, the entire Fellowship. In the end Saruman’s story is a sad one. Despite (and because of) the fact that all the sadness is self-inflicted.

They Must Be Mighty, But Forgo Might

Saruman is a wizard – an Istar in Tolkien’s terminology. He, along with four other wizards were sent by the Valar (the most powerful spirits in Tolkien’s cosmos) to aid and assist in the coming wars against Sauron. Realizing that Sauron – already quite the troublemaker in the past – was likely to be up to old tricks, the Valar got together to decide who would go. It was a difficult decision.

For they must be mighty, peers of Sauron, but must forgo might, and clothe themselves in flesh so as to treat on equality and win the trust of Elves and Men. But this would imperil them, dimming their wisdom and knowledge, and confusing them with fears, cares, and weariness coming from the flesh. (from The Unfinished Tales, “The Istari”)

It’s an interesting dilemma. The chosen ones would have to be strong, but also willing to give up that strength. Even though giving up that strength would make them even weaker. It’s an ominous mission statement. Saruman – then named Curomo – volunteered immediately.

The story continues with one of the Valar, Manwë, suggesting that Olórin (Gandalf) should also go.

But Olórin declared that he was too weak for such a task, and that he feared Sauron. Then Manwë said that that was all the more reason why he should go, and that he commanded Olórin [to go as the third]. But at that Varda looked up and said: “Not as the third;” and Curumo remembered it.

YIKES. It’s a rough start for Saruman. He seems like the brave one: immediately volunteering for a mission that suggests hardship and diminished stature. Then, he’s almost immediately overshadowed by someone who does not want to go, and says he is afraid. And this, it seems, became a trend for Saruman.

To Rekindle Hearts in a World That Grows Chill

The stated mission of the Istari was to aid the peoples of Middle-earth. They weren’t supposed to lead them, or muster them into armies – the Valar had them assume diminished statures so that they’d fit in, there to aid and help, not dominate. Like the rest of Tolkien, it’s a tale that insists upon free will. The Istari were to offer help. Everyone else could accept it or ignore it. Gandalf, of course, is great at this. And everyone recognizes it: Círdan the Shipwright entrusted him with Narya, the Ring of Fire, “to rekindle hearts in a world that grows chill.” Much later, Galadriel supported him as the leader of the White Council.

Saruman, of course, is not. There are a lot of differences to be talked about between the two wizards. Gandalf’s pride was tempered by a brusque-but-deep kindness and humility. Saruman’s was more deep seated and self-serious. Gandalf was largely mentored by Nienna, the Valar associated with wisdom through grief. Saruman was largely mentored by Aulë, a smith and craftsman. It is thus not surprising that Gandalf saw his role largely as a more passive (or responsive) role, while Saruman more actively crafted plans. Honestly, it’s hard for me to separate them from Cain and Abel – an older brother who creates (Cain tilled the soil) harboring an intense jealousy for a favored younger brother who guides (Abel was a shepherd).

But I’d argue that the key difference between the two is Saruman’s desire for control, and the pride that grew with it. Rather than wandering the land, Saruman established official relationships with Rohan and Gondor and built himself a centralized fortification. The core of his power – his voice – was designed to bring people to his way of thinking, to obtain control over them rather than to guide. As he began to slide further and further from his original mission, he even started to try to teach himself the craft of ring-making: when Gandalf approached Isengard before being taken captive in The Fellowship of the Ring, he noticed that Saruman was wearing a ring on his finger, something he had not done before.

It’s an understandable impulse. Saruman appears in his younger days as brash, fearless, confident (just imagine if he’d met Fëanor). Yet he feels himself constantly overshadowed by someone much more unassuming than himself. So he keeps working, keeps crafting, keeps planning pushing towards that indiscernible point that will bring him success.

Saruman and the Temptation of Control

And it’s this backstory that makes “The Voice of Saruman” – especially Gandalf’s conversation with the other wizard – so interesting and vibrant. So much of their history echoes in that final confrontation. Take Saruman’s last-ditch attempt to use his voices in a speech to Gandalf. It’s a powerful attempt, and wins over everyone else, at least for the moment. It casts a spell of magnificence, aristocracy over everyone else who listens.

Of loftier mould these two were made: reverend and wise. It was inevitable that they should make alliance. Gandalf would ascend into the tower, to discuss deep things beyond their comprehension in the high chambers of Orthanc. The door would be closed, and they would be left outside, dismissed to await allotted work or punishment. Even in the mind of Théoden the thought took shape, like a shadow of doubt: “He will betray us; he will go – we shall be lost.”

Saruman’s fantasy – his pitch to Gandalf – is one of control. That the two of them, in their pedigree and wisdom, ought to discuss the “deep things” beyond the understanding of others. Everyone else, including the king of Rohan and heir-apparent of Gondor, would simply await their “allotted work or punishment.” Saruman was never able to let go of this idea, to truly understand that his quest was designed to be one of service. Gandalf must have been such a mystery to him: a wizard who wandered among halflings, who seemed indifferent to power and then had people hand it to him.

And it must have been infuriating to him: when he made that final appeal, Gandalf does not even argue back. He just laughs. We know Gandalf well by this point. We’ve heard his speeches to Frodo and the Théoden about the essential quality of mercy. But it’s so fitting that Saruman, from his distant, paranoid purview, labels Gandalf’s mercy condescension and all his attempts to save Saruman as simply a long con. He denounces it as a secret plan to steal Orthanc and then:

the Keys to Barad-dur itself, I suppose; and the crowns of the seven kings, and the rods of the Five Wizards, and have purchased yourself a new pair of boots many sizes larger than those that you wear now. A modest plan. Hardly one in which my help is needed. I have other things to do.

There’s a weird sense of tragedy here that Saruman assumes that Gandalf has simply outplayed him. That he has been aiming at the same goals and simply playing a devious, two-faced game. Of course, we know that they weren’t playing the same game at all. And Saruman, for a painfully long time, was the only one who seemed to assume that they were playing against each other. So even in the end, when Gandalf offers him another chance to aid, to assist, as he originally had been sent to do, Saruman refuses. “Great service he could have rendered,” Gandalf said. But:

He has chosen to withhold it, and keep the power of Orthanc. He will not serve, only command. He lives now in terror of the shadow of Mordor, and yet he still dreams of riding the storm. Unhappy fool! He will be devoured, if the power to the East stretches out its arms to Isengard.

Saruman insists on maintaining his own control and his own autonomy until the bitter end. He perpetuates a pattern that he’s been performing for literally thousands of years. The more Saruman reaches for control and authority, the less of it he has, and the more desperately he reaches. Gandalf gives him a way out of this holding pattern. But Saruman rejects it, seizing instead a life of confinement (and later, a life as a petty tyrant over a land he has long disdained).

There’s a version of this whole story that could be told from the eyes of Saruman. It would be proud and sad and bitter, and always covered up by a cloud of narcissism. But it would be a good story. I’m sure he would have enjoyed telling it. But Saruman’s brittle, unyielding insistence upon his own independence only led to servitude. By insisting on authority, he lost control of his own story.

Final Points

- Another Saruman fun fact. In one version of the story, Tolkien had two Nazgul arrive at Orthanc while Gandalf was still prisoner. Faced with the blunt reality of his choices, Saruman panicked, lied to the Nazgul, and decided to help Gandalf escape. But when he reached the roof, Gandalf was gone and Gwaihir could be seen off in the distance. Having escaped without making any real choice, Saruman slid back towards his old ways. I’m not sure this would fit anywhere in The Lord of the Rings, but there’s a poignancy to it that I like.

- I appreciate Gimli’s continuing concern that he had mistaken Gandalf for Saruman on the edge of Fangorn. It seems very in-character that such a thing would be troubling to him.

- I knew it was coming, but it still made laugh that Gríma literally just chucks the palantír out a window. GREAT JOB, GRIMA.

Everyone’s interactions with Treebeard at the end of the chapter were perfect. Gimli & Legolas get one step closer to booking their vacation to Fangorn. And we get a sweet encapsulation of the friendship between Treebeard, Merry, and Pippin. “We have become friends in so short a while that I think I must be getting hasty – growing backwards towards youth, perhaps. But there, they are the first new thing under Sun or Moon that I have seen for many a long, long day.” I am going to miss the Ents, going forward. They’ve been such a lovely part of this book.

Everyone’s interactions with Treebeard at the end of the chapter were perfect. Gimli & Legolas get one step closer to booking their vacation to Fangorn. And we get a sweet encapsulation of the friendship between Treebeard, Merry, and Pippin. “We have become friends in so short a while that I think I must be getting hasty – growing backwards towards youth, perhaps. But there, they are the first new thing under Sun or Moon that I have seen for many a long, long day.” I am going to miss the Ents, going forward. They’ve been such a lovely part of this book.- I appreciated Théoden being tempted by Saruman’s words. He’s probably in the most precarious position. Even coming off a victory at Helm’s Deep, he’s still not many days away from a very long stint under Saruman’s influence. It also continues to underline the theme that hope is a continual choice, not a one-time affair.

- Prose Prize: “Here and there gloomy pools remained, covered with scum and wreckage; but most of the wide circle was bare again, a wilderness of slime and tumbled rock, pitted with blackened holes, and dotted with post and pillars leaning drunkenly this way and that.” Not beautiful exactly, but a nice striking image. I like the idea of drunken pillars.

- Contemporary to this chapter: Still March 5th!

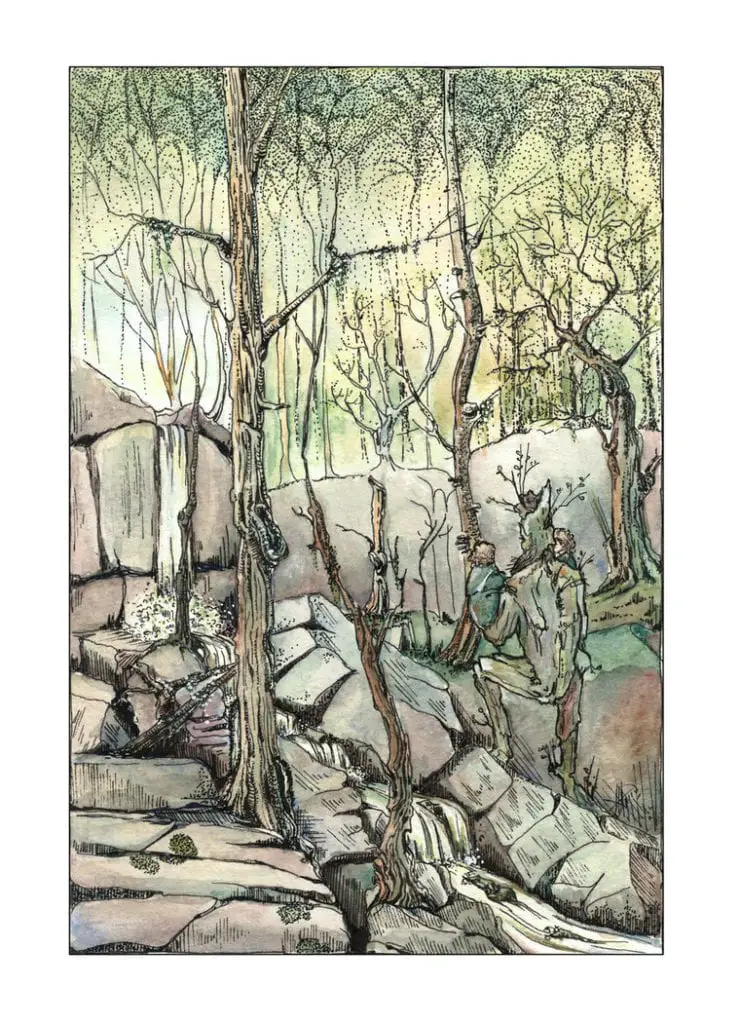

Art Credits: Film stills are from Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) courtesy of New Line Cinema. All other art, in order of appearance, is from Jian Guo, Miruna-Lavinia, and erzsebet-beast.