“The Scouring of the Shire” is perhaps the most distinct chapter of The Lord of the Rings. The epic quite suddenly becomes local; the mythic becomes petty. The Third Age gives way to the Fourth. This isn’t entirely true, of course—as Frodo states, this is Mordor, or simply one of its works. It’s a pot stirred up by Saruman, the last gasp of the final Third Age power broker to actively engage in affairs.

But more than that, I think “The Scouring of the Shire” is a bridge. It’s the story of The Lord of the Rings lifted out of its original context. We are dealing with the same themes of choice, misplaced ambition, the arrogance of arrogated power. Here, though, they simply exist. No need for a Ring to mediate their course. The problems that pop up all over the Shire are, on one hand, a lingering after-affect of all that’s occurred. They’re a reminder to the hobbits that they can’t expect their homes to remain untouched. But they are also a reminder to that the promised joy to come is something that requires work, sacrifice, and a complicated array of choices. And that problems are not a thing of the past.

It’s the narrative denial of a simple ending, the delay of any hope for a happy one. It’s clear from the first sentence of the chapter. “It was nightfall when, wet and tired, the travelers came at last to the Brandywine, and they found the way barred.”

Gatherers and Sharers

Lifted out of the previously-employed mythic framework, “The Scouring of the Shire” can feel like the most overtly allegorical of Tolkien’s chapters. As soon as the hobbits enter the Shire, it’s clear that a new political structure has taken shape, and for the worse. “Well no, the year’s been good enough,” said Hob, when asked why food couldn’t be shared and spared.

“We grows a lot of food, but we don’t rightly know what becomes of it. It’s all these ‘gatherers’ and ‘sharers,’ I reckon, going round counting and measuring and taking off to storage. They do more gathering than sharing and we never see most of the stuff again.”

Nefarious redistribution aside, the Shire is also riddled with cold, petty bureaucracy. As Frodo and the hobbits attempt to take refuge in a warm and cozy inn they are told the inns are closed, and that they can instead take refuge in a “Sheriff House” at the edge of the village.

It was a bare and ugly place, with a mean little grate that would not allow a good fire. In the upper rooms were little rows of hard beds, and on every wall was a notice and a list of Rules. Pippin tore them down. There was no beer and very little food, but with what the travelers brought and shared out they all made a fair little meal; and Pippin broke Rule 4 by putting most of the next day’s allowance of wood on the fire.

It’s… hard for me to not read this and hear echoes of some sort of Stalinist Hobbiton (or, if you’re less generous, an echo of the critique of the rise of welfare states in Allied countries after World War II). If someone were to insist on that reading, it’d be hard for me to argue against them all that hard. But, just for a sec, let’s pretend the author isn’t dead. In the Forward to The Lord of the Rings’ Second Edition, Tolkien insists rather vehemently that a political reading of the chapter is off-base:

An author cannot of course remain wholly unaffected by his experience, but the ways in which a story-germ uses the soil of experience are extremely complex, and attempts to define the process are at best guesses from evidence that is inadequate and ambiguous. …It has been supposed by some that ‘The Scouring of the Shire’ reflects the situation in England at the time when I was finishing my tale. It does not. It is an essential part of the plot, foreseen from the outset, though in the event modified by the character of Saruman as developed in the story without, need I say, any allegorical significance or contemporary political reference whatsoever. It has indeed some basis in experience, though slender (for the economic situation was entirely different), and much further back.

I mostly have sympathy of this, mostly due to the fact that if “The Scouring of the Shire” had a purposeful political message it would be largely incoherent. And, given the rural isolation of the Shire, it would have essentially nothing to say about any modern political economy. If you can argue that “The Scouring of the Shire” rails against the establishment of the welfare state, you can also make the case that it argues for forcible overthrow of the police, as seen when Sam chastises a local Sheriff named Robin. Robin asks for some leniency, asking

“What can I do? You know how I went for a Sheriff seven year ago, before any of this began. Gave me a chance of walking around the country and seeing folk, and hearing the news, and knowing where the good beer was. But now it’s different.”

“But you can give it up, stop Sheriffing, if it has stopped being a respectable job,” said Sam.

“We’re not allowed to,” said Robin.

“If I hear ‘not allowed’ much oftener,” said Sam, “I’m going to get angry.”

“Can’t say I’d be sorry to see it,” said Robin, lowering his voice. “If we all got angry together something might be done.”

In any case, any debate surrounding the political “meaning” of“The Scouring of the Shire” seems diverting at best, myopic, self-fulfilling, and purposeless at worst. Meaning, for Tolkien, is rooted in the personal. And evil is rooted less in any sort of politics than in general acts of spite (Saruman) and weakness (Lotho, to start with, then many others). There’s criticism to be found in that as well, of course—Tolkien’s violence is rarely systemic—but that’s for another post. For now, let’s take a look at the Scouring of the Shire in a narrative context.

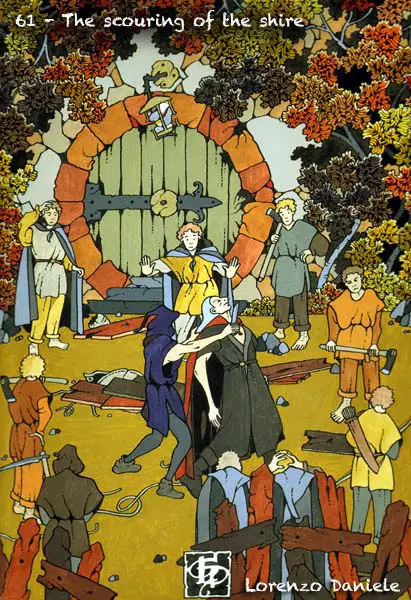

The Scouring of the Shire

The Scouring of the Shire largely does two things. It demonstrates that the pain and violence that wracked Middle-earth has not spared the Shire, and that the establishment of a prosperous Fourth Age will be a long, difficult endeavor. And it also demonstrates, on a personal level, what this means for Frodo and Sam, Merry and Pippin.

The Shire, in our hobbit’s absence, becomes the Un-Shire: as soon as they arrive, they note the new buildings to be “all very gloomy and un-Shirelike.” There has been purposeless destruction, quiet beauty has been needlessly upturned. There’s something—as Sam later notes—especially horrifying about the destruction of the Shire. It’s utterly unnecessary, and cruel. It’s allowed by textbook ambition and conventional greed, and it’s engineered by an utterly unnecessary act of pettiness. The new Sandyman mill is the starkest example: the vainglorious construction of a bigger mill that didn’t even possess the necessary input to produce more things, following by an industrial monstrosity that seems to exist solely to pollute and depress.

They saw the new mill in all its frowning and dirty ugliness: a great brick building straddling the stream, which it fouled with a steaming and stinking outflow. All along the Bywater Road every tree had been felled… All the chestnuts were gone. The banks and hedgerows were broken. Great wagons were standing in disorder in a field beaten bare of grass. Bagshot Row was a yawning sand and gravel quarry. Bag End up beyond could not be seen for a clutter of large huts.

On one level, the hobbit’s return to the changed Shire works as a case study to show that small acts of malice have not been undone by the destruction of the Ring. A better future requires constant vigilance and kindness. On another, it works as a thesis statement, uttered by Saruman and promptly countered by Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin, stepping into the roles that, as Gandalf noted, they had been “trained for.”

“I shan’t call it the end, till we’ve cleared up the mess”

One of the most interesting thing to me, about this chapter, is that the hobbits—though distressed!—rarely seem overly concerned about the fate of their home. From the start, they are almost startlingly confident. They break through the gate, immediately dispatch with Bill Ferny, and constantly laugh at the makeshift authority figures who try to run rampant over their home or stand in their way. Even as they approach Hobbiton and the scale of the problem becomes apparent, the hobbits laugh less but never seem in doubt about the outcome.

And, it turns out, there’s no need for them to be. Rather than attempting to use the deterioration of the Shire as a secondary climax (which would, by necessity, feel… underwhelming), Tolkien simply uses it as a commentary on the difficulties of homecoming after a grand adventure, and a way to confirm how much these characters have changed. Sam—who will really have his chance to shine next chapter—reconnects with the Cottons, helps defend Frodo, and foreshadows his rebuilding efforts in “The Grey Havens.” Pippin draws his sword to defend Frodo against ignorance and malice, then later musters and leads a unit of Took hobbits to the Battle of Bywater.

And Merry, most of all, really shines. He encourages the rousing of the Shire, noting that the hobbits just “want a match… and they’ll go up in fire.” He creates all the battle plans and executes them effortlessly. He even kills the lead ruffian in the final battle. It’s good to come to the close of our story seeing our characters so competent, ready to meet challenges that are sure to come.

Frodo and Saruman

Frodo, of course, feels a bit different. He is more passive, more empathetic, and slides effortlessly into his role as a moral leader in tandem with Merry’s military leadership. He encourages the rescuing of Lotho despite the hobbit’s role in the Shire’s deterioration. As soon as the need for conflict becomes more apparent, Frodo is increasingly insistent that killing be avoided, despite Merry’s reasonable point that Frodo can’t “rescue Lotho, or the Shire, by being shocked and sad.” His role in the Battle of the Bywater is to prevent unnecessary killing.

Frodo is a necessary balance to the Merry’s rabble-rousing (and rabble-organizing). And this becomes immediately clear with the revelation that Sharkey, the mysterious local boss, is actually Saruman. His explanation for his actions, unsurprisingly, is eloquent, petty, and pitiable.

“You made me laugh, you hobbit-lordlings, riding along with all those great people, so secure and so well-pleased with your little selves. You thought you had done very well out of it all, and could now just amble back and have a nice quiet time in the country. Saruman’s home could be all wrecked, and he could be turned out, but no one could touch yours. Oh no! Gandalf would look after your affairs.” Saruman laughed again. “Not he! When his tools have done their task he drops them… I have already done much that you will find it hard to mend or undo in your lives. And it will be pleasant to think of that, and set it against my injuries.”

Saruman’s power and his voice was always predicated on his ability to articulate things that were almost true, that seemed true, or that people feared to be true. I thought it a nice touch here that Saruman attempts to undercut Frodo and Company by playing on their fears that they have been callously abandoned to their fate by Gandalf. It’s something that could seem so close to true out of context, or something that could seem convincing to someone who didn’t know the hobbits at all. Frodo immediately makes it clear, though, that he is not tempted or convinced by Saruman’s narrative. He is quietly confident, unshakeable in his empathy. He simply tells the other hobbits that Saruman is to remain untouched.

“I do not wish him to be slain in this evil mood. He was great once, of a noble kind that we should not dare to raise our hands against. He is fallen, and his cure is beyond us; but I would still spare him, in the hope that he may find it.”

Frodo, passive for nearly all of The Return of the King, makes an active choice. It’s a culmination of his character arc as much as Merry’s. He allows someone who is an active threat to himself and those he cares for to live on, in the hopes that he can find peace, consolation, and betterment. Unfortunately, as with Gollum, Saruman lets him down. He immediately attempts to murder Frodo (and is later in turn murdered by Wormtongue). And he denounces Frodo’s offer.

Saruman rose to his feet and stared at Frodo. There was a strange look in his eyes of mingled wonder and respect and hatred. “You have grown, Halfling,” he said. “Yes, you have grown very much. You are wise, and cruel. You have robbed my revenge of its sweetness and now I must go hence in bitterness, in debt to your mercy. I hate it and you! Well, I go and I will trouble you no more. But do not expect me to wish you health and long life. You will have neither. But that is not my doing. I merely foretell.”

Saruman, as always, falls due to a failure of imagination. He sees Frodo’s actions as akin to his own, pity as a weapon to deny him pleasure rather than to open up doors to healing. He misunderstands Frodo almost entirely, but it does not stop him from seeing Frodo’s fate. Poor Frodo. It’s telling that the other three hobbits spend their time throughout this chapter making things happen. Frodo spends it trying to prevent more things from being lost. But more on that next time.

Final Comments

- I clearly have some Sam in me, as I too was horrified by the destruction of the Party Tree. That’s where the book started, you monsters!

- Rosie never really gets much characterization. But from what’s there she seems like a nice person and a good match for Sam. She can match his optimism (she’s been waiting for him since Spring!), teases and badgers him a bit, but also clearly admires him—and tells him so. I wonder if Sam married her because she was the only person to ever tell him he should care about Mr. Frodo more.

- Another glimpse of a hobbit lady: Lobelia trying to beat up armed guards with her umbrella is a nice moment. I’m looking forward to her brief appearance in “The Grey Havens” too.

- I enjoy the references (around since Bree) to the Shirefolks’ utter indifference to the hobbits’ journey. Like the guests at the Prancing Pony, the Cotton’s barely feign politeness at the tales from the four hobbits’ travels; Old Hob assumed Merry never made it past the Old Forest.

- Another nice touch—that “some of the village-folk had lit a large fire, just to enliven things, and also because it was one of the things forbidden by the Chief.” It seemed like a very realistic and human moment, that people held down for a while would gather together and break the rules in a fun and (so-far) meaningless way.

- Also quite liked the brief appearance of Ted Sandyman. “Don’t ‘ee like it Sam?” he sneered. “But you always was soft. I thought you’d gone off in one o’ them ships you used to prattle on about, sailing, sailing.” It’s a good reminder that not all Shire problems are imports.

- Saruman’s transmutation into mist is a surprisingly sad moment. It’s a bit wrenching that, despite everything, he thought he might be accepted back into the West.

- Prose Prize: All of Saruman at the end. I think I have some sort of thing for Tolkien villain / antihero monologues? Talk at me all day, Saruman and Denethor.

- Next Time: Yikes, finishing up things in January! We’ll take a look at “The Grey Havens” and close things off with a look at Peter Jackson’s finale. Maybe in the spirit of a new year I’ll be less mean this time. But probably not!

Art Credits: Art, in order of appearance, is courtesy of erzsebet-beast, TolmanCotton, Lorenzo Daniele, and aegeri.