Prison movies like Greg Kwedar’s Sing Sing are a dime a dozen. Artists traffic in empathy, and only a fool can look at the carceral system as it stands and think it is anything other than a force of penalizing evil. So, their films often depict the brutality and horrors of prison life while mixing in some harrowing melodrama.

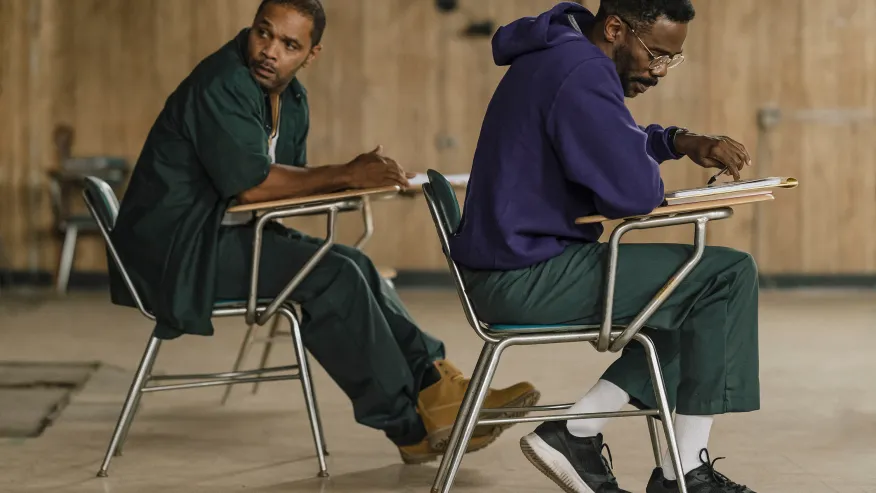

But the lack of melodrama separates Sing Sing from so many of its predecessors, aside from the performances so nuanced and delicate that you sit holding your breath for fear that the illusion may shatter. Kwedar’s film, based on John H. Richardson’s book The Sing Sing Follies about the artistic rehabilitation program at one of the country’s most infamous maximum security prisons, looks at the way the inmates seek to rebuild themselves and support their fellow inmates. It is a journey of the soul.

As one character says to Divine Eye, Clarence Maclin, who is not a character or an actor but an actual former inmate and member of the program, “We are here to remember how to be human.” The line is the film’s thesis statement. So much of prison life is about dehumanizing the men and women behind the walls, turning them into animals, and forcing them to live by a code built on anger and fear.

The RTA (Rehabilitation Through the Arts) program is designed to create a safe space for vulnerability and a place for brotherhood. Coleman Domingo’s Divine G is evangelical about the program. An innocent man wrongly convicted, he is a playwright, a self-taught lawyer, and the de facto leader of the group. It is he who suggests to the others that Divine Eye should join.

Here is where Sing Sing begins to falter. Kwedar, who co-wrote the script along with Clint Bentley, begin to sow the seeds of a kind of Shakesperean betrayal. Intentional, of course, but it shows the lack of trust and faith the script has in both the overall film and in the performances of Dominigo and Maclin. The other issue is how the script focuses solely on the two, leaving the other performances, which are as compelling as the two leads, feeling as if they are being brushed aside.

Domingo has established himself as one of the most reliable actors in the business today. No matter the project, Domingo shines, his mere presence raising any movie, no matter how shoddy, to the level of more than watchable. In his hands, Divine G is a character out of Shakespeare, doomed to be betrayed, not by his friends, but by the very system that put him in prison in the first place. As his clemency hearing looms, we see his insecurities and fears peek through the cracks of his confident facade.

Taking Divine Eye under his wing, he attempts to point him on the right path, secretly hoping he won’t be here to watch his journey. But Sing Sing works, Domingo aside, because of the real inmates playing themselves and the moments where the script refuses to bow to convention. Moments like the one where Divine Eye calls Divine G a slur radiate so powerfully because of Domingo and Maclin play the moment so quietly. “In here we say ‘Beloved’.”

Domingo is rightfully nominated for an Academy Award, but Maclin should be as well. It’s not as easy as people think to play yourselves. Maclin’s performance simmers with vulnerability. His bravado a mask for the pain and hurt boiling underneath. He holds his own in his scenes with Domingo, a feat that would garner any other actor a long and promising career. Maclin should at least be nominated alongside Domingo.

The play the inmates are putting on, Breakin’ the Mummy’s Code, is a real play they performed in prison. A hodgepodge of different stories and ideas that the program director wove together after the inmates pitched their own ideas that included everything imaginable plus the kitchen sink and Freddy Kruger. Some of my favorite moments are how the inmates try to wrestle with the play’s internal logic. Another small mercy the porgram grants, another brick in rebulding their humanity, the right to bitch about menainglss things.

The cast of Sing Sing is so effortlessly charming that you wish you spent as much time with them as you do with Divine Eye and Divine G. Characters like Dap, Big E, or the other actor in the bunch Sean San Jose’s Mike Mike, brim with life and with a versmiltitude that even their brief appearences hints at whole novels of stories untold.

Pat Scola’s camera dances between intimate and observant, feeling as if we are intruding on private moments. Scola and Kwedar keep Sing Sing so visually fluid that the runtime feels half of what it is. Despite the heavy drama, the movie never feels overly dour, with much of the brutal horror of prison life ignored or implied. Sing Sing is about watching prisoners rediscover their humanity after having it stripped away. Scola and Kwedar are not interested in wallowing in what brought the characters here.

Sing Sing joyously celebrates the power of the arts. Kwedar and Bentley’s script never wrestle with the racial and class issues bubbling under the film’s surface. At the same time, I can’t help but applaud a movie about prisoners seeking redemption that is so bereft of cynicism. Maybe it’s because of Domingo’s performance, but as much heartache as Sing Sing has, it brims with triumphant, almost defiant, joy.

Images courtesy of A24

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!