This is not an argument against spoiler culture, even if it has gotten a little out of hand lately. When actors aren’t even told what scene they are acting in, lest it be leaked and therefore dilute whatever value the piece of media had (because what even is rewatchability?) it is safe to say that sometimes the element of surprise is prioritized over cohesive storytelling. But again, that’s not what this article is about.

No, this is about spoilers that we don’t consider spoilers: the framing devices that we file away in our brain as we watch or read and which affect how we travel through the narrative. And which are also totally spoilers. Yet we even muster up the energy to be enraged over.

Looking at three specific examples— Romeo and Juliet, Titanic, and The Bell Jar— the pattern is clear, that these are spoilers which come early and temper reader/viewer expectations right from the beginning.

The first example comes straight out of everyone’s freshman year English classroom: Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. The chorus prologue famously opens the play, as was common for contemporary theater, with a brief rundown of what’s coming. “From forth the fatal loins of these two foes / A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life; / Whole misadventured piteous overthrows / Do with their death bury their parents’ strife.” The feud between the families, the star crossed lovers, their death and the deaths of others around them, all spoiled for everyone in Act 1, Scene 1.

But does that ruin everything for viewers? Of course not— there’s a reason the bard is still being read and performed. It gives the audience something to look for, a sense of dramatic irony, a sense of dread over the whirlwind romance.

The second example is from the 1997 blockbuster film Titanic, which famously has the framing device of Old Rose telling of her time on the doomed ship. Because of this framing, we know at the very least she is among the 700 survivors. That doesn’t mean we viewers still aren’t worried when Cal chases her with a gun or when she is trapped in steerage behind locked gates or when she’s left on that board in the freezing night. But it is never in doubt that she will live.

This still leaves plenty of room for surprises— the viewer does not know the fate of the “Heart of the Ocean” for much of the film. The viewer is still heartbroken by Jack’s fate. Rose’s survival is as foregone a conclusion as the ocean liner’s sinking, but there is still a story worth watching.

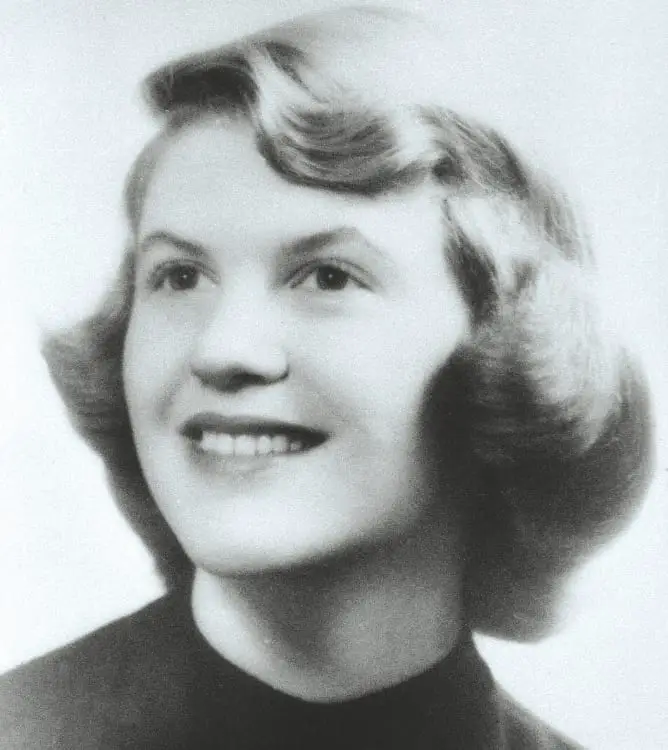

The third example is from Sylvia Plath’s semi-autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar. It is the subtlest, but perhaps the most comforting, of the three. A line from the narrator, Esther Greenwood, right from early in Chapter 1: “I got such a kick out of all those free gifts showering on to us. For a long time afterward I hid them away, but later, when I was all right again, I brought them out, and I still have them around the house. I use the lipsticks now and then, and last week I cut the plastic starfish off the sunglasses case for the baby to play with.”

That later, when I was all right again is so powerfully subtle in a book about depression, hospitalization, and suicide attempts. Right from the beginning, the reader is given the most important spoiler of the book— our protagonist ends up alright. And there are many moments in the subsequent twenty chapters where that seems unlikely, especially with the cloud of Plath’s ultimate fate hanging over her only novel. This means that the subtle assurance from the first chapter is an important relinquish of a technical spoiler.

These three examples justify the idea that the important element to a story that a spoiler could—hence the name— spoil is the how not the what. The what is the root of rewatchability. The what is an indication of a well thought out narrative, one that doesn’t rely solely on the sensationalism of surprising viewers.

Knowing how Romeo and Juliet’s star-crossed love ends in blood is far more important than that it will, which is why Shakespeare had no qualms about letting that one spill in the prologue. Knowing that Rose survives the sinking of the infamous shipwreck does nothing to lessen the tension dripping out of the entire second half of the film, which is why James Cameron chose her to be the narrator. And knowing that Esther Greenwood’s depressive spiral is eventually overcome only enhances the warped, heart-wrenching experience of reading her go through it.

The three particular examples above span theater, literature, and film. They span 400 years of narrative innovation. But they are connected with the thread of a writer who intentionally dropped a spoiler which we don’t think of as spoilers almost immediately in the beginning of their story.