People (nerds) have already spilled bottles of ink over the fate of Éowyn in The Lord of the Rings. Some find her romance with Faramir and her change of heart a fitting and satisfying end to her character’s series-long arc. Some find it a betrayal, a last-minute shunting of the story’s primary female heroine, who had regularly eschewed traditional gender roles, into the “safe” role of wife and healer. And… both of these are true! So, come on, friends. Let’s talk about some feminism.

“I Looked for Death in Battle. But I Have Not Died.”

Let’s get this out of the way right up front: pretty much any question about the appropriateness of Éowyn’s character arc would have evaporated on arrival if Tolkien simply had more women in his story. As we’ve noted here before, Tolkien is… sparing with the women who appear in his story (though when they show up, there’s often better than their modern fantasy counterparts). Éowyn is one of the only women in The Lord of the Rings. She’s certainly the only women to so clearly question the gender assumptions of her society.

So when Éowyn declares that she “will be a shieldmaiden no longer nor vie with the great Riders, nor take joy only in songs of slaying. I will be a healer, and love all things that grow and are not barren,” it can feel like that narrative is going back on its promise. It’s easy to assume that Tolkien intended to say all of her earlier critiques and actions had been misguided, or “wrong.” Éowyn wanted to go out and fight with the guys, but she would have been happier nursing and cultivating all along.

This becomes especially difficult to swallow when this transformation occurs as she falls for a handsome prince/steward whom she had just met. Her courtship with Faramir, on several occasions, seems predicated on Éowyn “weakening” herself. When she demands that Faramir let her leave the Houses of Healing before the doctor-prescribed time, “her heart faltered, and for the first time she doubted herself,” fearing that Faramir will find her childlike and petulant. On another occasion, talking to him, Faramir notes that her voice became “like that of a maiden young and sad.” Out of the context of her entire story, this feels very much like Éowyn attaining happiness by softening her edges, by giving up her earlier demands to become a maid, uncertain and waiting to be saved from her sadness.

And… none of that is exactly incorrect. Where I question that strand of criticism, though, is in its tendency to reduce Éowyn to Valiant Fantasy Warrior Maid, whose narrative role is to defy the men keeping her down. If that were simply who she was, her ending would absolutely be a betrayal. But Éowyn’s story has always been more complicated. Her desire to cast herself headlong into battle has always been both deeply understandable and deeply misguided: a fusion of justified anger at her restricted role and a misplaced glorification of battle that borders on a lust for self-harm. Éowyn is not a badass fantasy warrior who just wants to fight. We’re never told that she loves sword-fighting, or tactics, or cavalry formations. Éowyn loves the idea of fighting, the lifestyle of it, those riders who get to go out and make choices and affect their own futures. She is a person whose life has become some terrible and so circumscribed that she feels her best option is to blaze out in battle. Perhaps people will sing songs about her. Better that than to have leave to be burned in the house, when the men will need it no more.

By the time she reaches The Houses of Healing—and honestly, well before that—this desire has verged on the suicidal. “I looked for death in battle,” she tells Faramir in their first meeting. “But I have not died.” So, so much of Éowyn’s story has been centered on choice, and how it is almost always denied to her at every turn. You get the sense, reading The Lord of the Rings, that her attempts at choice were whittled down so far that death would be welcome to her, so long that it was something that she chose. But then she was not even allowed to do that.

Éowyn and Faramir

Faramir, of course, allows Éowyn to choose.

It’s the heart of their relationship, and it means that it works better thematically than as a palpable romance (Faramir seems to think Éowyn pretty and sad; she seems to think him pretty and nice). Things move pretty fast—which, eh, the world’s ending and they are both pretty, have fun, kids—and their chemistry is nothing to write home about. But I think it works nicely as a thematic end to Éowyn’s story. Things start off by seeming like more of the same: Faramir won’t let Éowyn ride off to chase after Aragorn and the armies marching on the Black Gate (rightly pointing out she wouldn’t be able to catch up in time anyway). But after that, Faramir leaves the agency largely to Éowyn. After their first meeting, he simply tells her that they can meet more if she’d like, at her discretion.

“You shall walk in this garden in the sun, as you will; and you shall look east, wither all our hopes have gone. And here you will find me, walking and waiting, and also looking east. It would ease my care, if you would speak to me, or walk at whiles with me.”

It’s such a kind offer of support to someone in Éowyn’s position. He lets her know that he would like to spend time with her but also leaving the choice entirely up to her. They spend most of their time together simply sitting or walking and talking, coming to understand each other and the commonalities of their past. And, eventually, he asks her to choose what she wants. And she does.

Then the heart of Éowyn changed, or at last she understood it. And suddenly her winter passed, and the sun shone upon her.

I, uh, have this engraved in wood and hanging on my wall. It’s very simple, but it also means a lot to me. So much of Éowyn’s story is so very sad, and so much of her action through the story is driven by desperation, by a drive to assert herself that’s so strong that she’s willing to destroy herself in the process. In this context, Éowyn’s turn at the story’s end is not a betrayal of her integrity as a character or a patriarchal demotion. It’s a moment of brightness. That with such a slight shift, and with just a bit of help, she was able to turn and warm and choose and grow. For me, at least, Éowyn was never a “feminist” character primarily because of her pushback against Middle-earth gender norms. Rather, Éowyn was a “feminist” character because of her constant assertion of her right to be able to make choices about her own life, even in the face of widespread pushback from those who cared about her most. In the end, she was finally able to choose. And her life was better for it.

The Return of the King

So much of this chapter focuses on the stories of Faramir and Éowyn that I’d nearly forgotten that it’s also the chapter where Aragorn is crowned king, enters Minas Tirith, finds a Nimloth sapling, and gets married (!). Life gets busy when you’re a king, I guess.

Aragorn is quite remote by this point in the story. So while there are some nice moments here, everything also feels very elevated, very lofty. Kate Nepveu has noted that in a book that starts and ends very heavy on the hobbits, “The Steward and the King” is the clear low-point of hobbit saturation. And it shows! It’s a more formal, cooler, more aloof chapter than those that surround it, so much of Aragorn’s actions here are things that I appreciate but care about largely in abstraction. There are still some good ideas floating about, though.

The first, and largest, is simply the sense of loss embedded all of this. It’s funny: Aragorn’s reign is Minas Tirith’s canonical golden age. Tolkien notes specifically that under his rule the city became “more fair than it had ever been, even in the days of its first glory.” But there’s still a sense of sadness, stretching forward and stretching back. Gandalf articulates the obvious one, the one that’s been highlighted throughout the series: that things that were will be lost.

“The Third Age of the world is ended, and the new age is begun; and it is your task to order its beginning and to preserve what may be preserved. For though much has been saved, much must now pass away.”

I like that the nostalgia here—“much must now pass away”— is twinned with potential growth. The language focuses on saving and on preservation, but the fact that this sits cheek-by-jowl with the command to Aragorn to order the Fourth Age’s beginning is a nice reminder that in Middle-earth loss is often accompanied by possibility.

Of course, the inverse is true as well. Even at the high point of Minas Tirith’s history, there is a sense of impermanence. Tolkien notes that after Aragorn’s coronation, the city was

filled with trees and with fountains, and its gates were wrought of mithril and steel, and its streets were paved with white marble; and the Folk of the Mountain laboured in it, and the Folk of the Wood rejoiced to come there; and all was healed and made good, and the houses were filled with men and women and the laughter of children, and no window was blind nor any courtyard empty; and after the ending of the Third Age of the world into the new age it preserved the memory and the glory of the years that were gone.

It’s a beautiful picture, bright and happy. But the sudden perspective shift into the ambiguously-distant future almost creates its own sense of sadness. Jumping forward to give the encapsulation of Aragorn’s glorious reign functions to make it feel to the reader as though that were in the past as well (which, canonically, it is). It’s an interesting combination. Tolkien is using very old forms and archaic systems in most of his handling of Aragorn in this chapter. But he’s using them to convey a sense of transience, of continual change and momentum.

And while it’s a bit on the nose, I do enjoy Aragorn’s rediscovery of the White Tree, and Gandalf’s insistence that “if ever a fruit ripens, it should be planted, lest the line die out of the world.” It fits in quite nicely with the themes of growth, renewal, and cultivation that are littered throughout the end of the story. We see some of it here in Éowyn’s reorientation towards healing and growth and we’ll see it more later in Sam’s upcoming replanting of the Shire.

Final Comments

- Aragorn apparently makes peace with the Easterlings and Harad after the fall of Mordor. They are still hard for me to reckon with, as part of Tolkien’s world. They are such ciphers and such others in the story, and problems quickly arise no matter what reason you ultimately settle on for why they served Sauron.

- “The hands of the king are the hands of a healer, I said, and that was how it was all discovered. And Mithrandir, he said to me, “Ioreth, men will long remember your words, and – ” I was a little annoyed by Ioreth back when we first met her in “The Houses of Healing” but I was kind of charmed by her here? Honestly, who am I to say, that if I got to talk with a wizard and hang out with the new king on his first night in town and help him do is healing, I wouldn’t tell absolutely every person that I knew.

- I laughed out loud at the phrase “the harpers that harped most skillfully.” Which is fine linguistically, I guess, but is also a ridiculous phrase, J.R.R. Also, in related news: harp comes from Proto-Germanic harpon, also the source of Old-Saxon harpa, or “instrument of torture.” Please make fun of all your harpist friends accordingly, even those that harp most skillfully.

- I enjoyed it very much that Éowyn moped around Minas Tirith, passive-aggressively ignoring her brother’s invitation to the Field of Cormallen. And then when Faramir shows up to ask her about it, she almost immediately yells at him to speak plainer and just express his feelings.

- One more word on Éowyn: I think her story fits nicely on Tolkien’s attitude towards war and battle itself. She is arguably the biggest battle hero of the entire book, and she’s praised for that. But war is at best a grim necessity in Tolkien’s moral universe. The Rohirrim’s battle lust is often viewed as someone childlike and immature. Even the best warriors don’t put too much stock in the glory of battle. The level to which Éowyn elevates it was never going to be good for her or for anyone in this story. But Tolkien is also aware that Aragorn’s attitude towards war comes from a place of privilege that Éowyn does not possess.

- High Point of Faramir Seduction: When he respects her boundaries but lets her know that she is welcome to chat and go for walks with him if she wants to. Yeaaaahhhh.

- Low Point of Faramir Seduction: When a few days after meeting her, he decks Éowyn out in his dead mom’s star cloak. He is pleased by how pretty and sad it makes her look. Yikes.

- Prose Prize: And they went up by steep ways, until they came to a high field below the snows that clad the lofty peaks, and it looked down over a precipice that stood behind the City. And standing there they surveyed the lands, for the morning was come; and they saw the towers to the City far below them like white pencils touched by sunlight, and all the vale of Anduin was like a garden, and the Mountains of Shadow were veiled in a golden mist. Upon the one side of their sight reached to the grey Emyn Muil, and the glint of Rauros was like a star twinkling far off; and upon the other side they saw the River like a ribbon laid down to Pelagir, and beyond that was a light on the hem of the sky that spoke of the Sea. The whole thing is rather nice, but the last bit cinched it. “A light on the hem of the sky that spoke of the Sea.” That’s so lovely.

- Next time, on November 28th, we’ll dive into “Many Partings.” As far as I can remember it is a chapter where everyone hangs out and is friends and give each other presents. But in a slow, melancholic way because, well, that’s the tone into which we’re heading. See you then.

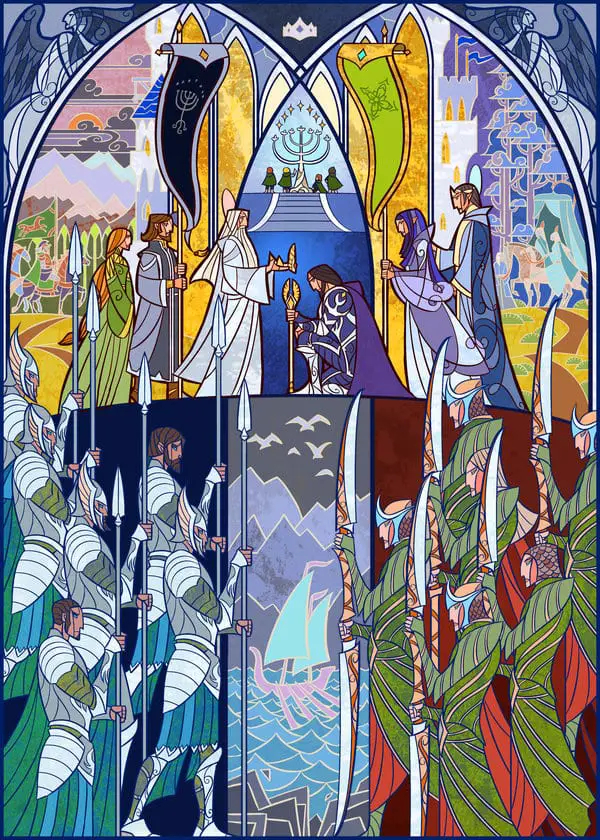

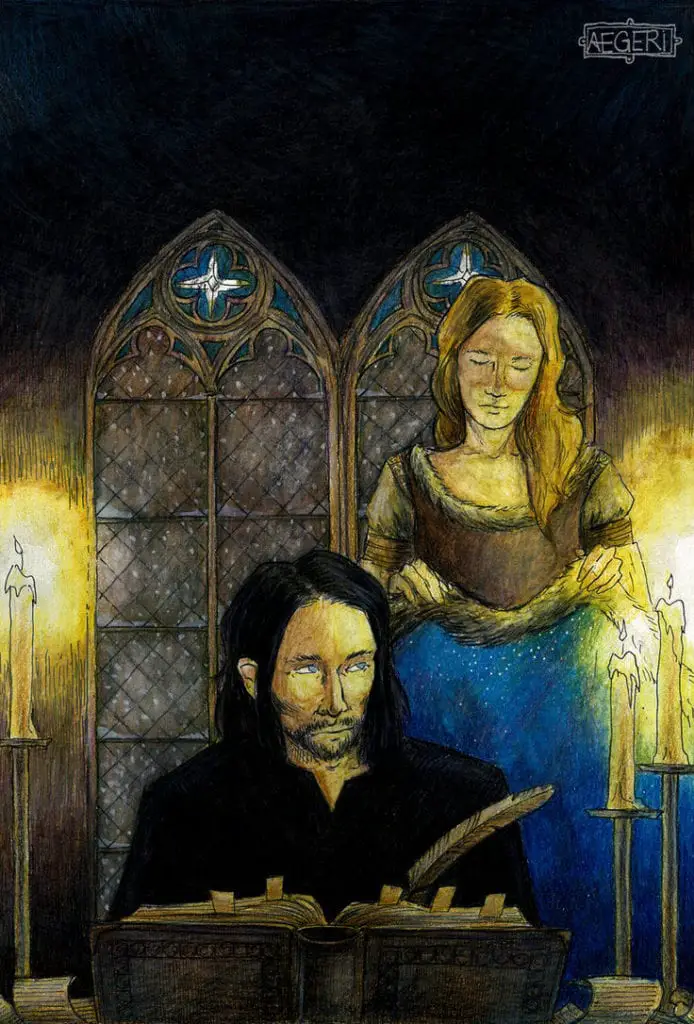

Art Credits: Art, in order of appearance, is courtesy of Snow-Monster, s-u-w-i, Jian Guo, and aegeri.