No better place to talk about stories than in a chapter that is so concerned with them. I’ve been looking forward to the end of The Two Towers for months now. For that sweet spider action, of course. But also because it exemplifies so much of what makes The Lord of the Rings work. Stories work when they feel real. Measuring authenticity is tricky: you could cite emotionally-resonant character arcs, meticulous world-building, careful plotting, or even grittiness (but yuck, don’t). You could also cite contextuality: the ability to make scenes exist on more than a single level, the ability to make moments exist beyond themselves.

Making a moment work on multiple levels is just good storytelling. It’s economical, it’s precise. It also injects the story with a shot of reality: events, reactions, have ripples. Single moments, single decisions have weight that flow out to affect other concurrent events. A good story, a realistic story, has lots of small stories, small histories, small desires, that bang into each other in unexpected ways and add up to something more. That sense of context and ramifications help create a realistic world more than an airtight magic system even will. And it’s something that Tolkien does really well in “The Stairs of Cirith Ungol.” Buckle in, friends, we’ve got a long one ahead.

Minas Morgul

“The Stairs of Cirith Ungol” is basically a triptych. It opens with the arrival at Minas Morgul and the exodus of one Sauron’s armies. It centers on Frodo and Sam having a conversation about the nature of stories and their place within them. And it closes with Sméagol’s final assertion of himself and its accidental, incidental dismissal. Each one is very big and very small; each one deals with past and present. And they all affect each other.

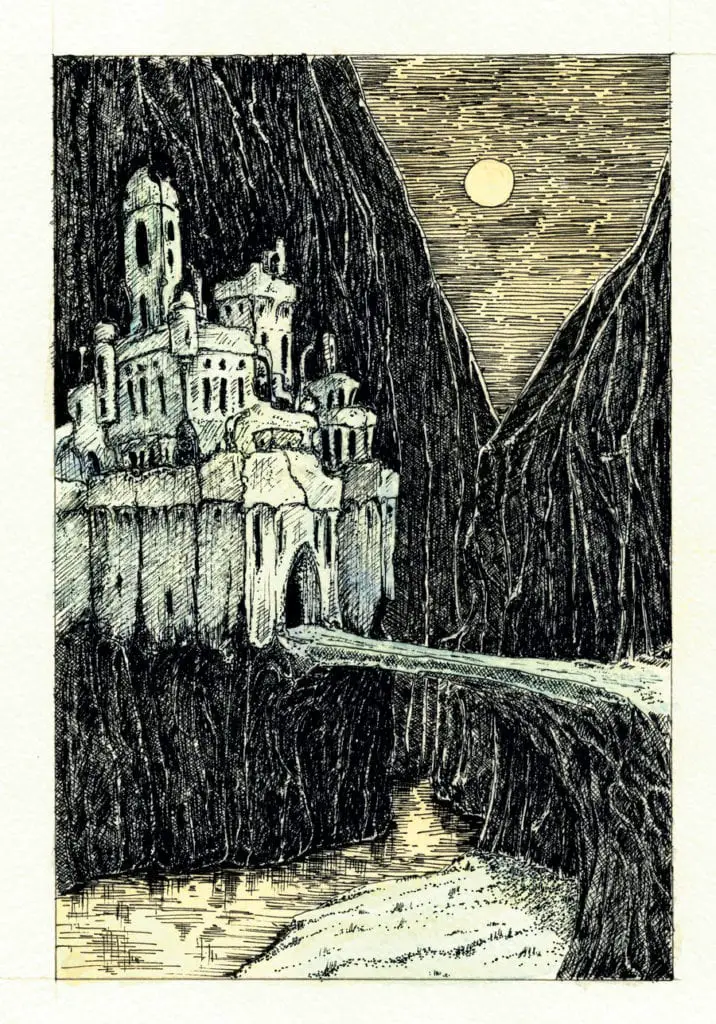

Minas Morgul is one of the best set pieces in Lord of the Rings. It is ominous and oddly beautiful, on occasion feeling like a horror-inverse of Lothlórien (Frodo’s turn to the Phial of Galadriel, then, works doubly well). It is carpeted with luminous white flowers, “beautiful and yet horrible” like something from an “uneasy dream.” Like so much of the evil in Tolkien’s work, it’s something that’s been distorted, twisted, made wrong.

High on a rocky seat upon the black knees of Ephel Dúath stood the walls and tower of Minas Morgul. All was dark about It, earth and sky, but it was lit with light. Not the imprisoned moonlight welling through the marble walls of Minas Ithil long ago, Tower of the Moon, fair and radiant in the hollow of the hills. Paler indeed than the moon ailing in some slow eclipse was the light of it now, wavering and blowing like a noisome exhalation of decay, a corpse-light, a light that illuminated nothing.

It’s a very cool location on its own, and Tolkien is on his A-game in description. “Lit with light” should be a silly phrase (uh, yeah Tolkien, it was probably lit by light). But instead it takes on a sinister turn. It quickly becomes clear that whatever it’s lit by, it isn’t really light – it’s an odd, pale, “corpse-light.” Weak, but an inevitable, infectious cloud. It’s lit and not-lit, by a light that’s also a not-light.

But it’s also a locale that works on multiple levels. First and foremost, it’s a challenge and a threat to Frodo and Sam. It also works as a reintroduction to Sauron and Mordor, a thematic re-emphasis on their propensity to twist and deform in the absence of an ability to create. And then there’s the fact that Minas Morgul, while a threat to the hobbits, does not care or even know about them. They are entirely concerned with something else.

There was a flare of livid lightnings: forks of blue flame springing up from the tower and from the encircling hills into the sullen clouds. The earth groaned; and out of the city there came a cry. Mingled with harsh high voices as of birds of prey, and the shrill neighing of horses wild with rage and fear, there came a rending screech, shivering, rising swiftly to a piercing pitch beyond the range of hearing… As the terrible cry ended, falling back through a long sickening wail to silence, Frodo slowly raised his head. Across the narrow valley, now almost on a level with his eyes, the walls of the evil city stood, and its cavernous gate, shaped like an open mouth with gleaming teeth, was gaping wide. And out of the gate an army came.

One of my favorite things about Minas Morgul in this scene is that it feels so much bigger than an obstacle for Frodo and Sam to squeeze past. While all of this is happening, an army spills out of the gate entirely unaware of them, off to fight a far-off battle. But it’s immediately emotionally resonant: because Frodo and Sam know the people whom the army is off to challenge, and because of the strong symbolic connections at play: the pale, twisted tower that had once been Minas Ithil is spewing out an army heading towards Minas Tirith. Stories are sliding by each other here. But it doesn’t make the narrative feel messy or overcrowded. It makes it feel vibrant, realistic, and fraught.

The Darkness of the East

Despite all of these overlaps, it would still be easy for “The Stairs of Cirith Ungol” to feel hollow. There are neat confluences, sure, but that counts for little if it doesn’t mean anything. Through Frodo, though, this all becomes an intensely personal experience. Frodo’s been having a tough go throughout most of Book IV – the Ring has only gotten heavier upon approaching the mountains surrounding Mordor. But at Minas Morgul, for a moment, the terror of the place seems to push him temporarily over the edge.

Frodo felt his senses reeling and his mind darkening. Then suddenly, as if some force were at work other than his own will, he began to hurry, tottering forward, his groping hands held out, his head lolling from side to side.

It’s small moment in the grand scheme of the chapter, but it’s so unsettling. Frodo feels his mind dimming, and then he essentially gets hijacked. It’s a terrifying moment, as if his own self, the thing that makes him Frodo, suddenly winks out. It’s the scariest moment in a chapter filled with screeching monsters, alien lights, poisoned flowers and massive armies. The Morgul Vale, for a moment, erases Frodo. It’s such an important moment, a perfect encapsulation how Middle-earth at its best can be both vast and intimate.

The sheer size of everything, the weight of history, is very present in this moment, but all that really matters is whether Frodo can recover himself. Even once he feels himself again, he totters: “Other armies will come. I am too late,” he says to himself. “All is lost. I tarried on the way. All is lost. Even if my errand is performed, no one will ever know. There will be no one I can tell. It will all be in vain.” It’s not, but it almost feels like a meta-commentary: how Frodo is so small, so singular, in a world in which so much is happening. And Frodo manages to keep going by keeping his focus studiously narrow. “Whether Faramir or Aragorn or Elrond or Galadriel or Gandalf or anyone else ever knew about it,” he thinks, “was beside the purpose.”

He’s right and he’s wrong. It’s besides the purpose but it also is the purpose. Because for Tolkien the personal and political, internal and external, are inextricably wrapped up in each other. Scale, to a certain extent, doesn’t matter. Armies march, cities come under siege, people make decisions without anyone to see. They can’t be separated – a philosophy only underlined by the fact that as Frodo grasps Galadriel’s phial, Lothlórien itself is coming under attack, and is ultimately saved by Frodo’s ability to keep a hold on himself and turn away the Witch-King’s attention.

Stories and Tales

The middle section of “The Stairs of Cirith Ungol” is one of the sections of The Lord of the Rings that I remember reading as a kid with the most clarity. It felt Very Important to me when I was twelve.

“Beren, now, he never thought that he was going to get the Silmaril from the Iron Crown in Thangorodrim, and yet he did, and that was a worse place and a blacker danger than ours. But that’s a long tale, of course, and goes on past the happiness and into grief and beyond it – and the Silmaril went on and came to Earendil. And why, sir, I never thought of that before! We’ve got – you’ve got some of the light of it in that star-glass that the Lady gave you! Why, to think of it, we’re in the same tale still! It’s going on.”

“…Still I wonder if we shall ever be put into songs or tales. We’re in one, of course; but I mean: put into words, you know, told by the fireside, or read out of a great big book with red and black letters, years and years afterwards. And people will say: ‘Let’s hear about Frodo and the Ring!’ And they’ll say: ‘Yes, that’s one of my favorite stories. Frodo was very brave, wasn’t he, dad?’ ‘Yes, my boy, the famousest of hobbits, and that’s saying a lot!”

“It’s saying a lot too much,” said Frodo. “…But you’ve left out one of the chief characters: Samwise the stout-hearted. ‘I want to hear more about Sam, dad. Why didn’t they put in more of his take, dad? That’s what I like, it makes me laugh. And Frodo wouldn’t have got far without Sam, would he, dad?’”

“Now Mr. Frodo,” said Sam. “You shouldn’t make fun. I was serious.”

“So was I,” said Frodo. “And so I am.”

It’s such a lovely little moment between Frodo and Sam before everything goes quickly downhill. It also, once again, ties them to the bigger picture in time and space. Frodo’s turn to the Phial of Galadriel in the Morgul Vale doesn’t just tie the story to the concurrent attack on Lórien. It also ties Frodo to the broader history of the world for which he’s fighting. It’s personal and far-reaching, and such a kind, bright moment in a dark place.

It’s also a moment for Frodo to reflect on his experience. In his struggle in the Morgul Vale, he notes at one point that he feels as if he “looked on some old story far away.” In that context, it was a largely negative thing: he felt powerless, stripped of himself, as if watching someone else act for him. Here, though, stories – and the ability to distance oneself from a distressing present – can bring comfort. It’s a nice parallel between the beginning and middle of the chapter, and once again places a clear emphasis on Tolkien’s focus on choice and intention. Which brings us to the last section of the chapter.

Gollum and Sméagol

Gollum’s story has been a sad one since the start. He’s been brutalized and traumatized, he’s a tragedy and a genuine threat. He’s spent most of The Two Towers veering back and forth between his two potential selves, toying with each outcome but ultimately still walking a middle path between the two. He was both Sméagol and Gollum, though often more one than the other at any given time. And at the end of “The Stairs of Cirith Ungol” Sméagol asserts himself as strongly as he ever has.

Gollum looked at them. A strange expression passed over his lean hungry face. The gleam faded from his eyes, and they went dim and grey, old and tired. A spasm of pain seemed to twist him, and he turned away, peering back up towards the pass, shaking his head, as if engaged in some interior debate. Then he came back, and slowly putting out a trembling hand, very cautiously he touched Frodo’s knee – but almost the touch was a caress. For a fleeting moment, could one of the sleepers have seen him, they would have thought that they beheld an old, weary hobbit, shrunken by the years that had carried him far beyond his time, beyond friends and kin, and the fields and stream of youth.

It’s a moment that’s as hopeful as Sméagol’s story could get at this point. A sad, weary old hobbit who is very lonely, but also one that would have the potential of finding some peace. But it doesn’t last. Sméagol startles the hobbits awake, Sam yells at him, and “the fleeting moment had passed, beyond recall.” It’d be easy to place the blame on Sam. And to suggest that if he had been kinder, perhaps Sméagol could have regained more ground. But I don’t think that’s entirely fair. At this point Gollum / Sméagol is an accumulation of failures, tragedies, moments of happiness and success. Just like anyone would be. He was teetering and then tipped too far. It’s not Sam’s fault. It’s not anyone’s fault. It’s just something that happened, and it’s very sad.

It’s a dark bookend on a chapter that had quite a bit of brightness in the middle. Stories have their power, and there are always choices and differing outcomes – but sometimes that’s not enough. It’s a sad moment, and a reality in Tolkien’s world. But it’s not the only outcome. After some spider adventures in Shelob’s lair, after all, we’ll get to the choices of Master Samwise.

Final Comments

- I went to an art history talk last week that discussed Islamic paintings under Mongol rule. This was one of the paintings, and the scholar made a joke about the, ermm, geological implausibility of the mountains. I couldn’t stop laughing because they are Mordor mountains.

- I’m really fond of Frodo’s moment of panic near Minas Morgul. It’s a very identifiable moment in which a dutiful character carrying an impossibly heavily burden finally slides down the slippery slope to worst-case-scenario thinking.

- Frodo’s ability to hold onto himself is, of course, bittersweet. He’s able to keep going, but the cracks forming in him are already visible. When he mentally chooses not to put on the Ring, he reasoning is based heavily on the fact that he’s not strong enough to challenge the Witch King – “not yet.”

- Prose Prize: High on a rocky seat upon the black knees of Ephel Dúath stood the walls and tower of Minas Morgul. All was dark about It, earth and sky, but it was lit with light. Not the imprisoned moonlight welling through the marble walls of Minas Ithil long ago, Tower of the Moon, fair and radiant in the hollow of the hills. Paler indeed than the moon ailing in some slow eclipse was the light of it now, wavering and blowing like a noisome exhalation of decay, a corpse-light, a light that illuminated nothing. It’s so good! So good. There’s the “lit with light” / “hollow of the hills” in the middle and the sense of build – the second and third sentence have three main clauses, balancing each other, and then the last had a fourth, giving it that extra sense of momentum, like it’s spilling over. Just the best.

- Tolkien’s Wanton Cruelty to Innocent Punctuation Marks (sponsored by Mytly): I didn’t notice anything this time! Am I becoming desensitized to punctuation cruelty? I don’t blink at anything less than four semicolons and six em-dashes anymore.

- Contemporary to this chapter: Denethor sends Faramir to Osgiliath. Armies attack both Rohan and Lothlórien. Aragorn takes his sweet time meandering around with the Army of the Dead. Things are escalating quickly

All film stills are from Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003) courtesy of New Line Cinema. The rest of the images, in order of appearance, are from erzsebet-beast, Ted Nasmith, Lorenzo Daniele, and Anne Olga Vea.