Nobody ever said that being a part of the most exciting medium of storytelling was going to be easy. Allowing the audience to play a role in your art brings its own challenges as well as opportunities. Video games must have mechanically sound gameplay. Fail that, and a great story might be overlooked.

There is no parallel to draw from another medium; novels, movies, plays and television shows have no comparable mechanic they must master. Video games live or die by whether or not the gameplay and the story are in sync.

There is no simple or set answer for how a developer can marry gameplay mechanics to their story. In an attempt to help illustrate the conflict, I have come up with five rules for avoiding gameplay and story segregation. Each rule will come with an example of a game that is let down by not successfully marrying gameplay to story. Each rule will also come with an exception, and in every single case that exception will be Silent Hill 2 (there is a reason this game is a masterpiece).

Rule 1: Gameplay Must Be ‘Fun’

The hint is in the name. Video games are a kind of entertainment, and thus games should be fun. If they are a chore to play, then a player will likely not bother. Provided they are provoking some sort of emotional response in the player (beyond boredom or frustration), a game can be described as ‘fun’ in my book.

Six Days a Sacrifice, the final installment in the Chzo Mythos saga by famed game critic Ben ‘Yahtzee’ Croshaw, tells one of the most intricate, inventive, and incredible stories I have ever had the good fortune of experiencing. Unfortunately, it is also an old-school style adventure game. It is plagued with inventory puzzles and an awkward point-and-click interface. It is a chore to play, particularly in its first half as the story builds slowly and quietly. The eventual denouncement is excellent, but the lack of fun in its gameplay means I will likely never play it to completion ever again.

Fun, therefore, is an essential part of gaming. Yet ‘fun’ is a relative concept that does not always line up with the dictionary definition of fun. Horror games employ tension and dread to create an emotional high for the player. This still counts as ‘fun’, and thus does not fail the rule. The premier example of this exception is Silent Hill 2.

Protagonist James Sunderland must also solve illogical inventory puzzles, but the ‘fun’ is not undermined thanks to the constant tension the game employs. Dreading what is beneath a hatch when you finally manage to open it can go a long way to distract you from the insane way in which the game expects you to open said hatch. (The solution involves a horseshoe, a lighter and a wax figurine. I dare you to try figuring it out).

Rule 2: Avoid Deliberate Frustration

Do not, under any circumstances, think you can get away with deliberately frustrating a player. This goes hand in hand with the ‘fun’ problem just discussed. If a player is not enjoying themselves on some level, then you have failed as a game designer. Do not be fooled into thinking this frustration will be forgiven if you do it for story reasons.

The infamous bottle puzzle in Life is Strange is widely derided for good reason; it is boring, poorly implemented, and utterly destructive to the pacing. However, it is clear what the developers intended. The idea was to have the characters indulge in pointless recklessness while distracting the player from the building tragedy. That way, when the tragedy struck, the player would feel responsible.

This is good storytelling, but it is also horrific game design. It does not matter how strong the eventual emotional gut punch succeeds in being (and yes, it is absolutely heart-breaking, but that is beside the point), it will never make up for the half hour I spent wandering aimlessly around an obtusely designed junkyard as I slowly lost my goddamn mind. The fact that the frustration was intentional is not a saving grace, it just makes the design even more galling.

Silent Hill 2 gets away with having frustrating combat mechanics because of its genre. Feeling powerful is the antithesis of horror. It is fine that James is difficult to control in a fight because that increases a player’s sense of vulnerability. Every enemy, from recurring grunts to boss monsters, can kill you if you are careless. In this case the frustrating gameplay leads the player to fear every threat, thus ensuring that they are still ‘enjoying’ the experience on some visceral level.

Rule 3: Dissonance, Ludonarrative or Otherwise, is Dangerous

When making a game, be very careful about not creating dissonance between your story and gameplay. If the player starts to find themselves at odds with the ‘heroic’ protagonist then any emotional investment is compromised. The developer must carefully consider every action of the player character before shipping a game for sale.

Nathan Drake, wisecracking hero of the Uncharted series, is an unrepentant mass murderer. His body count is in the thousands. The story tells me he is a charming rogue. I want to believe he is a charming rogue. Yet it is hard to overcome his utter (and unintentional by design) disregard for human life.

His lovable persona in cutscenes simply does not square with his sociopathic slaughtering of his fellow man in gameplay. This is an all too common flaw of action games caused by developers failing to consider the reality of the violence being employed by the player character. The challenge is in creating a player character whose role in the story is not dissonant with their actions.

Silent Hill 2 subverts this challenge by making the dissonance deliberate. We start on James’ side as he faces horrors in the search for his wife. The more we get to know him, however, the more we start to feel unease. The dissonance between the player and the player character works because James is not being painted as a hero. Questioning his motivations is the point, not an unintentional side-effect of wanting exciting violence in your game.

Rule 4: A Player Must Retain Control

If a game promises the player is in control, then they must remain so. The cheapest thing a game can do is to steal control away from the player so that its story can continue as intended. Either a game is strictly linear or the player can dictate the story. Trying to do both will invariably damage your game’s quality.

Witcher 3 is ordinarily excellent at allowing the player choices that dictate the fates of characters and countries. Its expansion Blood and Wine is less so. At one crucial juncture in the story Geralt (the player character) is given a handful of days to track down Dettlaff (the central antagonist). Dettlaff has promised to attack the city if he is not presented with his former lover who betrayed him.

Clearly there are two paths Geralt can now take, yet the player does not get to make the decision. The story abruptly jumps forward a few days with Geralt having failed to find Dettlaff. The city is attacked because of Geralt’s failure. This demonstrates a complete breakdown of established gameplay mechanics because the writers needed the city to be attacked for the sake of the story.

Silent Hill 2 gets around the problem of choice by having the plot be 95% linear. The player can only impact the very end of the game through their choices. As the ultimate resolution is usually what people care most about, this allows the writers to dictate their preferred pacing without making the player feel as though they have no control.

A whole host of subtle things you do inform the state of mind of James Sunderland. Examine his wife’s photo frequently and James will end the story devoted. Examine a knife frequently and James will end the game suicidal. This level of subtlety is in stark contrast to the blatant ‘cut to a few days later’ that Blood and Wine pulled.

Rule 5: Justify Your Interactivity

This is the big one. If there is a clear conflict between a game’s story and its gameplay, a player might ask why this story is being told in an interactive format at all. The best way to avoid players asking this question is to ask this question of yourself before you sit down to make the game.

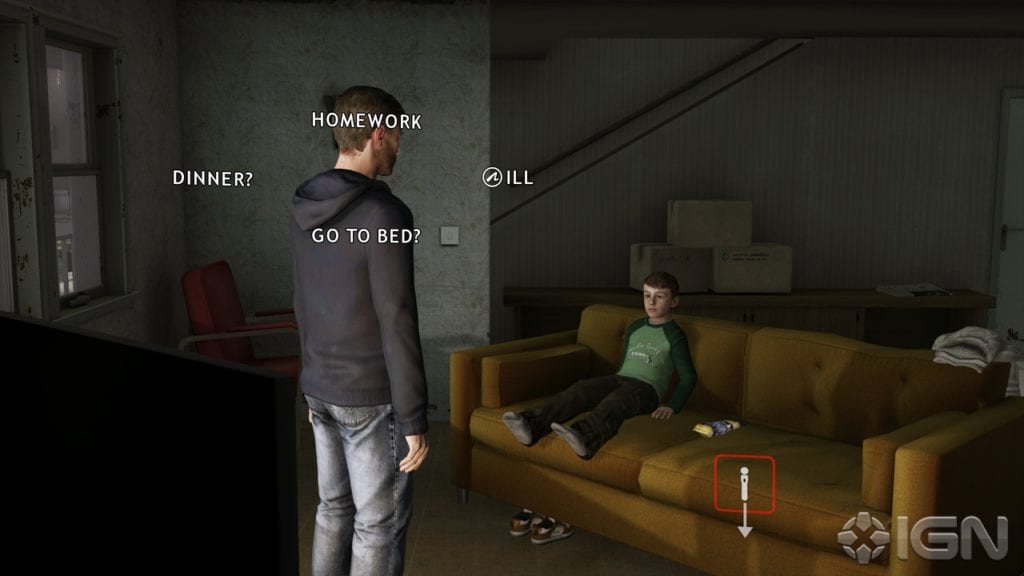

This is a question I really wish David Cage would ask himself. His games (Heavy Rain, Beyond Two Souls) are all styled like movies with minimal interactivity present. There is no good reason for these awkward hybrids to be video games aside from the fact that Cage probably cannot get backing from a movie studio for his grandiose yet also somehow boring ideas. (Incidentally, even as movies these games would still be terrible, as Cage cannot write a cohesive narrative to save his life. But I digress…)

Silent Hill 2 tells an excellent story. Would this story work in another medium? Could it be successfully adapted into a movie, a television series or a novel? Yes it could, the story would still work and the final product would still be worthwhile.

Yet in no medium could it ever hope to be as effective as it is already as a video game. This is the best possible medium for horror because of interactivity. The player immediately relates to the protagonist because, in a sense, they are the protagonist. It is thus far easier to make them fear what they protagonist fears.

Creating empathy is immensely difficult when telling a story. Sympathy is easy, as all it requires is a halfway likable character to befall some sort of misfortune. Having someone actually experiencing the same emotions as the character is hard to pull off, but Silent Hill 2 uses the unique conventions of its medium to do so effortlessly. It unequivocally justifies its interactivity.

Bonus Rule: Pure Gameplay Is Also Fine

Tetris has no story. Tetris is one of the best games ever made. These two statements do not contradict each other.

A game does not always need to tell a story. It is a unique medium in that it can survive without any narrative whatsoever. Tetris is pure gameplay and no less rich for it. If the gameplay is strong enough (and that is a big if) the game can survive without a single story beat or contextualizing detail.

However, as fun as these things can be, I still see the future of gaming as being a narrative one. Compare Tetris to Portal. Both are pitch-perfect puzzle games, but one also tells a rich and entertaining story. The path from one game to the other was a three decade long process of trial and error. The medium is richer for being able to produce art like Portal when once Tetris was the absolute pinnacle of what could be achieved in video gaming.

And just in case you were wondering, yes, the opposite of the bonus rule is also true. Pure storytelling is also fine. The thing to bear in mind, though, is in that case it stops being a game at all and literally becomes a movie. Gameplay cannot be divorced from the medium, even if storytelling can.

Conclusion

Is it arrogant of me to come up with all these rules of game design when I have never designed a game? Is it not my business to come up with rules to guide people doing a job I could never do myself? The answer to the first question is probably yes, but I would dispute the second question’s validity. Any and all artistic mediums need a thriving environment of critique to sustain themselves. If there were no one around to point out flaws then we could never learn from them and progress.

As I said at the top of this piece, no one ever claimed that making good video games was easy. It requires an enormous amount of technical knowhow and storytelling proficiency. It is perhaps the most challenging medium in which to create something truly worthwhile.

Yet with great challenge comes great potential rewards. Get the right balance of gameplay and storytelling and some random Irish guy will praise your achievements all day long. I am sure this sort of adulation is exactly what Team Silent were after when they sat down to make Silent Hill 2.

In all seriousness, balancing gameplay with storytelling is a maddeningly difficult enterprise. Games like Witcher 3, Life is Strange and Uncharted 2 are all great despite not nailing the landing. It may be that perfectly balancing the two is impossible. That said, even if perfection is beyond us we should still strive to reach it. That way when we inevitably miss there is a decent chance we will have created something great regardless.