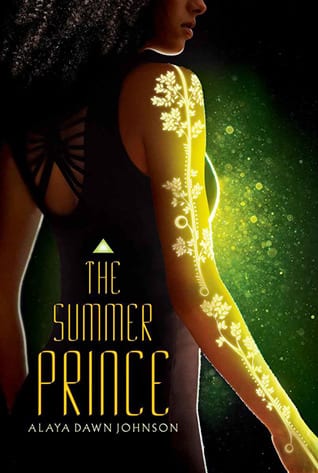

Alaya Dawn Johnson’s The Summer Prince is a YA post-apocalyptic dystopia. It’s set in a Brazilian city called Palmares Tres. Palmares Tres is one of the few cities you’d actually want to live in after a nuclear war left much of the world uninhabitable. This fictional city was named after the real 17th century city of Palmares, which was founded by runaway slaves and eventually destroyed by the Brazilian government.

Current societal issues like homophobia and sexism are non-issues in Johnson’s Palmares Tres. Moreover, the ruling “Auntie” class forces genetic “mods” on its populace so everyone looks fairly similar. This, in theory, put an end to racism. Interestingly, Palmarinas also have a kind of reverse-ageism that privileges people over 35. Palmares Tres’ government is a matriarchal, elective monarchy with a bad habit of sacrificing their so-called Summer Kings to the ancestors, and herein lies the plot.

What this thing is about exactly:

What this thing is about exactly:

June, our protagonist, is obsessed with the current Summer King, the enigmatic Enki. They team up to create art installations that wake the ruling “Auntie” class up to the issues of the day. Because Palmares Tres does have issues—how else would it earn the moniker “dystopia?” The city has sharp class divides. Palmarinas seem to have little to no interest in helping the impoverished communities surrounding their city. And, most pertinent to June, the Aunties strictly regulate which new technologies are allowed in. (It’s also really invasive to genetically “mod” your populace, but The Summer Prince doesn’t dwell on that so neither will I.)

The Summer Prince and real-life problems

In short, Palmares Tres has problems, but they’re mostly the same kind of problems we have in real life. The UN is investigating poverty in the U.S., it’s so dire. Not to mention we’re turning away far more refugees than we have in the past, and the FCC might get rid of net neutrality. This timeliness is especially striking when The Summer Prince is compared with other big YA dystopias like Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games. (You knew I was going there, right?)

The Panem-shaped elephant in the room

The Hunger Games kind of has something to say about poverty and classism. But Panem is so extreme it feels removed from the contemporary world. By contrast, day to day life in Palmares Tres isn’t bad at all. Our protagonist spends her days going to school, creating graffiti, and being rude to her stepmother. June and her friend Gil hang out and never worry about being forced to kill each other. June has enough leisure time to put Christmas lights in her skin for fun.

Moreover, Johnson consistently describes Palmares Tres as beautiful, inviting, and green. Heck, even the slums have a certain beauty. By comparison, Suzanne Collins consistently describes Katniss’ home, District 12, as bleak, lifeless, and gray. Honestly, I was a little hesitant to call The Summer Prince a dystopia. Palmares Tres seems so nice, mostly! But therein lies the rub, I’d say. Even the reader is seduced into thinking that Palmares Tres is worth the sacrifice.

A realistic dystopia? Say it ain’t so!

Johnson crafted a setting that is completely fine if you can ignore the same things we ignore. If you can ignore the slums, the refugees, the regular public murder. By writing this kind of setting, Johnson created something that Suzanne Collins didn’t: a believable dystopia. Sure, the idea of a futuristic society with human sacrifice is a stretch. But the concept of a hunger games was a stretch too. And I’d argue the Summer King tradition isn’t too different from how we look the other way while black men and boys are shot for seeming “suspicious.”

Negativity ahead:

The Summer Prince is not a perfect book by any means. I didn’t much like the pacing or the world-building. I really wish one of the central themes had been introduced earlier. The text never reconciles June’s disdain for authority with her desire for adult approval, either. Most importantly, Alaya Dawn Johnson has been criticized for cultural appropriation. I’m not qualified to say how valid these critiques are. But Johnson is American, and though she’s visited Brazil, I’m willing to believe she got some things wrong.

Still…

Despite its flaws, I’d say The Summer Prince is worth the read. It’s one of the most impacting dystopias I’ve read, and it does this by being subtle. It’s hard to see how a western society could turn into The Hunger Games. It’s easy to see how a western society could turn into Palmares Tres. Some of them are already halfway there.