A few years ago, while I was replaying the Mass Effect trilogy again, I decided to change how I usually would play the game. I would make different decisions, do different quests, and try to see how my experience would change. Mass Effect had always seemed so wide open with so many different options. I was sure my experience would be completely different. So when not much of anything changed at all, I was a bit surprised. It was then that I saw past the writing and perceived the truth behind all player choice based video games. In the end, your choices can’t really matter.

Of course your choices can’t really matter in a plot based video game. Imagine a pyramid, with the start of the game at the base of it and the ending at the top. You have dozens, sometimes hundreds of different options and choices. Each choice you make affects another. As you go up the pyramid though, your choices become more and more limited, until finally you reach the end and see that no matter what choice you made during the game, it all led here. And that’s because of the technical and financial limitations of game development. There simply isn’t enough time in development or money in the world to make every choice made by every player meaningful. Not to mention there isn’t a console or PC strong enough to support a game where every choice was important.

Because it’s actually impossible to make every player choice meaningful, developers have to find a way to hide this fact, Wizard of Oz style. And in order to draw the player’s attention away from the man behind the curtain, different companies have developed various different strategies. Some companies, like Bioware, write large stories that contain hundreds choices that affect the current game and ones in the future. Smaller companies try to mask decisions by clever writing and narrative based gameplay. And there’s one name that stands out when you mention narrative driven gameplay: Telltale.

Telltale will remember that

Telltale Games were well known for their narrative episodic games. At their best, they told stories that people loved and completely immersed the player. At their worst, their games went in circles and ended poorly. But for good or ill, most of their games, despite what the game itself would sometimes tell you, were linear. You would move from Point A to Point B in every episode. Sometimes there would be little deviations, but by the end of the episode, each character was where they needed to be to set up the next part.

Let’s take the first season of The Walking Dead as an example. In the first episode, no matter what you choose to do, you’ll always end up on the farm and then traveling with Kenny. In the second episode, you always ended up at the hotel, etc, etc. Other Telltale games follow the exact same formula. We can focus past it in the first season of The Walking Dead because the writing is constantly firing on all cylinders. In other Telltale games, the writing starts to slip and we can more easily see the formula. And once you see the formula, there really is no going back.

Games made by David Cage and Quantic Dream have similar issues, if not slightly worse. David Cage once told an interviewer to never play his games more then once, as that ruins the ‘magic’ of it. I don’t know if it would ruin the magic of it, but I know that in a lot of his games, the illusion of choice would be shattered completely if you went back and played them again. The biggest example of this happens in the game Beyond: Two Souls where it is impossible to get a game over, no matter what the player does.

The player chooses which particular scene occurs, but after that they have no real input if the character fails. You’d get the same experience from selecting random scenes on a DVD. And since the story of Beyond is presented haphazardly, it’s very easy to discover how little your choices actually matter.

The Bioware Formula

I mentioned earlier that I discovered the ‘story telling pyramid’ when I was replaying Mass Effect. That’s not exactly fair to the games, or to Bioware themselves. I had played their games for years without noticing anything. The flaws in Bioware games and other massive RPGs don’t come from the quality of the writing, but from the specific style and quantity of choices they give.

To tackle that first point, a lot of Bioware games have a specific style to them. The player generally starts as young, but somewhat experienced fighter/soldier/orphan. During the first act, their home/planet/mentor gets attacked, and the main character is marked in some way, and after that marking the main character begins to experience strange dreams. It is then revealed that the main character is the chosen one and their dreams contain some sort of special significance, usually prophetic. Lots of RPGs contain similar plot structures, but Bioware RPGs tend to follow this structure to a T. Baldur’s Gate, Knights of the Old Republic, Mass Effect, Dragon Age, Jade Empire… All of these games follow the Bioware formula, and after the third or fourth time playing one, you begin to see it clearly.

The other issue that Bioware games often have seems to be a positive at first glance. Specifically, the way they interconnect their games. After all, if you interconnect your games, you can have multiple quests from the previous game affect the next one. In essence, intersecting two pyramids on top of one another. What ends up happening though is that the variables become too much to keep track of. At some point, you start to write yourself into a corner, with no easy way out. Either you ignore previous choices made by the players, or you leave people unsatisfied. The writing of future games also takes a hit, as so many plot elements have been affected by player choice, the writers begin to run out of interesting plot threads.

The way the entire Mass Effect trilogy played out is a prime example of this flaw. So many quests piled on, and so many decisions were made that changed so much of the story that Mass Effect Andromeda had to be be set in another galaxy to get away from the weight of player choice and give the writers room to work.

Writing Works

So far, I’ve talked a lot about games and genres that make it easy for players to see that their choices don’t really matter. What about games that do? What makes them different? The answer generally comes down to the writing quality. More engaging stories tend to keep the suspension of disbelief going. Another aspect is a simpler game style. With less money needed for graphics or voice acting, more time can be spent on crafting seemingly meaningful decisions.

A good example of the the former category is The Life is Strange series, particularly the first season. Like The Walking Dead, the episodes are linear and you will end up in the same place no matter what. Unlike in The Walking Dead, you have the option of choosing one option, deciding you didn’t like it and rewinding time to see the other option. There are certain side quests you can’t get unless you rewind time, and even though the story would progress the same no matter what, having this extra little option helps distract players and increases immersion.

An RPG that does a good job of integrating multiple games worth of quests is The Witcher series. Like Mass Effect or Dragon Age, there are quests that carry over from one game to the other. Unlike Dragon Age, the plots in The Witcher games aren’t direct or even indirect sequels. There is very little connecting one game to the other, aside from a few throwaway lines that reference the previous games and some characters. This loose connection allows the writers to not have to worry about contradicting themselves, and gives them room to maneuver.

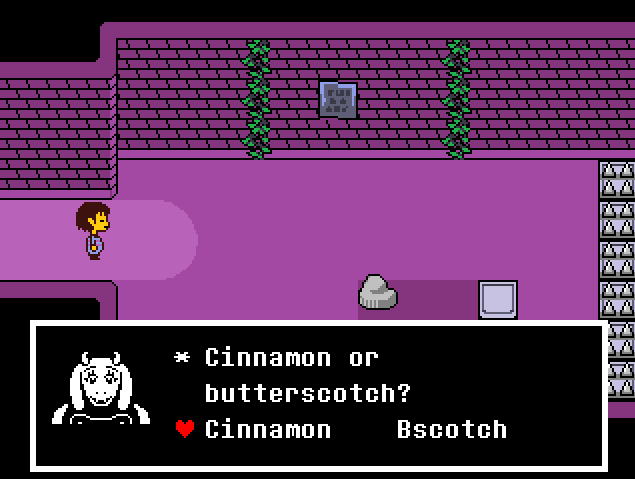

There is no one game that embodies how having a simpler game and good writing helps then Undertale. The choices (or rather, choice) in Undertale is very binary: “Do you kill, or not?” Depending on your answer to that question you will get one of two endings. Despite this, the game does a very good of making the player feel like an active participant in the story. When given a choice of dialogue options, characters in the game will remember what you say, when you say it.

Even tiny choices that the players might forget about, such as picking between cinnamon and butterscotch, will be mentioned again. This level of detail is only possible because Undertale is not a graphics heavy, voice actor filled game. The highest quality voice acting you’ll see in Undertale is some laughter. And yet in spite of that, Undertale hides it’s binary choice better then some games with five times the budget.

The Future of Choice

I’ve painted a fairly bleak picture of narrative choice in video games. Three companies that either hide their linear paths poorly or give the player too many options at the expense of coherent future games. Is this all we have to look forward too?

Well…no. Undertale does a great job of writing around it’s flaws, and it’s not the only game that does so. Pyre does an amazing job of it. And The Stanley Parable is literally all about the dichotomy of player choice vs the limits of what video games can do. As more and more games with this theme come out, mainstream games will have to work harder to disguise it. Add to that increases in technology and more smaller scale RPGs in development…at some point, player choice will matter.