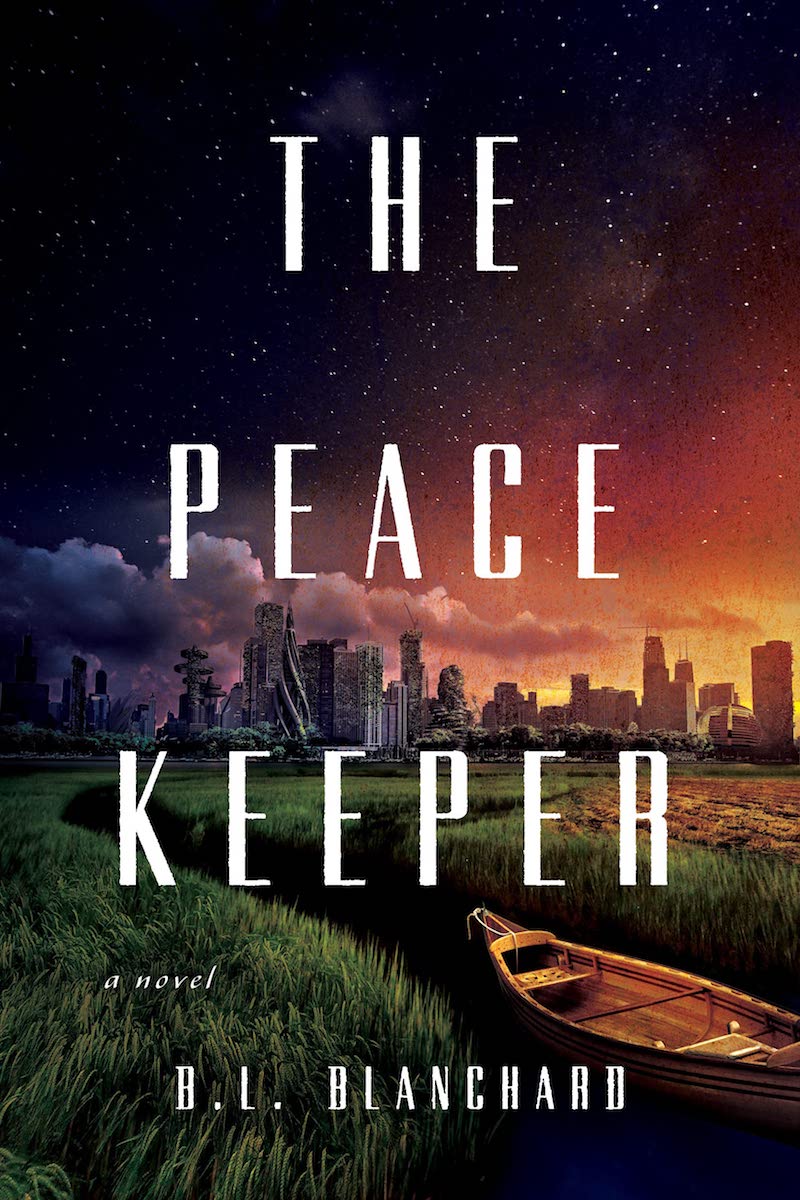

If you’re a true crime or mystery fan looking for a fresh, challenging perspective on justice and grief, I highly recommend picking up B. L. Blanchard’s The Peacekeeper. An engaging, well-paced murder mystery set in an alternate version of North America, it’s perfect for beach trips, staycations, and taking a break from the world in order to re-imagine what it could look like.

Against the backdrop of a never-colonized North America, a broken Ojibwe Peacekeeper embarks on an emotional and twisting journey toward solving two murders, rediscovering family, and finding himself.

A Brief (Spoiler Free) Run-Down

In B. L. Blanchard’s world, North America was never colonized, the United States and Canada don’t exist, and the Great Lakes are surrounded by an independent Ojibwe nation. In the village of Baawitigong (our universe’s Sault Ste. Marie in Ontario, Canada), a Peacekeeper confronts his devastating past.

Twenty years ago to the day, Chibenashi’s mother was murdered and his father confessed. Ever since, caring for his still-traumatized younger sister has been Chibenashi’s privilege and penance. Now, on the same night of the Manoomin (wild rice) harvest, another woman is slain: his mother’s best friend. The leads to a seemingly impossible connection that takes Chibenashi far from the only world he’s ever known.

The major city of Shikaakwa (our universe’s Chicago, Illinois) is home to the victim’s cruelly estranged family―and to two people Chibenashi never wanted to see again: his imprisoned father and the lover who broke his heart. As the questions mount, the answers will change his and his sister’s lives forever. Because Chibenashi is about to discover that everything about those lives has been a lie.

The Good Stuff

Two words: WORLD. BUILDING. Yes, I know that’s typically one word, but sometimes, the emphasis is more important.Seriously, this is one of the most interesting “alternate North American” histories I’ve read in years. Blanchard offers an image of what a non-colonized North America might look like that’s lush and vivid and fully realized without being overly saccharine. There’s still pain here, still flaws. It’s not perfect, but it’s pointedly anti-colonial in a way that highlights what America could have been if not for the utter tragedy of European imperialism.

Moreover, the vision Blanchard has of an alternative justice system is breathtaking in both its creativity and its challenge to our current prison industrial complex. Even the name of Chibenashi’s job, Peacekeeper, is a stark reminder that our version of this role in our society does anything but.

“Our system of Peacekeeping is one of restitution, of making people whole. This is all we come here to do today. This isn’t about assigning blame or punishing the Accused. Rather, this is about restoring the past…Now, we cannot change the past. What happened is what happened, and [the Victim] is not asking us to change that. She simply wants what is fair, what will best approximate this rewind of the clock.”—p.98

When I first read that, I couldn’t breathe. I’d never envisioned a justice system that held these values, much less one that functioned according to them. And Blanchard gives us a reasonable picture of what that could be. Is it perfect? No. She clearly believes (as I do) that there is no perfect justice, but she also believes (as I do) that we can do a hell of a lot better than what we have now, and creates a picture of what that could be that feels both beautifully plausible and devastatingly improbable. How do we get here? That’s what I want to know.

As for the story itself? It’s a beautiful story of grief and loss and the haunting nature of sudden trauma, a eulogy to missing and murdered Indigenous women, and underneath it all, a cry for justice for such women that’s so lacking for them in our society. In our world, missing and murdered Indigenous women rarely get the attention in true crime circles that white women do, much less justice. And that’s assuming their stories get mentioned at all. In this world without colonialism, people care about murdered Indigenous women and expend time and effort to discover what happened to them because they have the resources and structural support to do so instead of such women being ignored or victim-blamed.

Rather than a cynical man with a chip on his shoulder, Chibenashi is a grief-stricken and-guilt-ridden caretaker unable to access his feelings because he has no space to. He’s not toxically masculine, he’s poignantly fragile in the wake of great tragedy. He’s haunted by his own perceived failures, burdened by taking care of his even more emotionally devastated sister, and unable to cope with his own feelings for fear of losing himself and compounding his sense of failure. I connected to him deeply, given my own experiences of grief, trauma, and caretaking an emotionally damaged person. Much as I wanted to shake him for many of his choices, I sympathized with every one of them and the reasoning behind them, which is the mark of well-executed characterization.

The final thing that struck me is how much the story of murder resonates with the anti-colonialist worldbuilding. Just as the person who killed Chibenashi’s mother stole his future, European colonizers stole this vision of a North American future from the Indigenous Peoples. Ultimately, colonialism is the true murderer of a future that never existed for all the Indigenous peoples of North America. The most painful present isn’t Chibenashi’s, it’s our own, one that’s filled everywhere with what’s missing, what’s been lost by the destruction of Indigenous nations and the theft of their land.

“The goal of Mediation was to make people whole, not avenge them. It was to make the perpetrator atone for what they had done, not punish them for it.”–p.186

We, the white colonizers, have destroyed and must seek the kind of mediation this story offers: we must do what we can to make Indigenous People’s whole. There are things we can do to best approximate the rewind of the clock, and if we in the US are to have a better future, we must atone for what we have done and make restitution that best puts Indigenous communities in a position to be whole.

Potential Drawbacks

My only disappointment with the novel was the motive. Everything else about the reveal made sense in a satisfying way. All the clues are there, and I think Blanchard does a good job offering the right balance of evidence and red herrings. The revelation of who committed these crimes is as well done as some of my favorite Christie murder mysteries. It was the why that didn’t fully connect with me. Not that it wasn’t reasonably established, I could look back and see the clues. Rather, it’s a motive I’m just not that enthused about in a general sense rather than it being specifically a result of how the story is told.

However, your mileage may vary! I entirely own that this is a matter of taste, and with everything else about the book being as top tier as it is, even my disappointment wasn’t enough to ruin the overall great experience reading this. I’ll be looking for more mysteries like this from B. L. Blanchard, especially if she keeps up the thoughtful, evocative worldbuilding. Honestly, I’d love to erad more stories in this specific setting.

Some may find the use of Indigenous words overwhelming, but honestly, I didn’t find it distracting at all. If you’re comfortable reading fantasy novels or sci-fi with conlang, you won’t have any issues here. Plus, Blanchard provides a glossary at the end of the novel that’s helpful if you want to know exactly what the words mean.

Final Score: 9/10

This is a different kind of true crime story. A story about grief and caretaking and missing and murdered Indigenous women, a story about justice and what it looks like when you center wholeness and re-creation, a story about what’s lost when we belief the myths of our families and communities instead of seeing clearly. Andfor me as a white person, it’s ultimately a story about what colonialism has destroyed and stolen as well as a path for how we can make restitution for what we’ve done.

If you like true crime and mysteries but aren’t into carceral feminism and American copaganda, I cannot recommend this more highly.

“A purely punitive approach to life accomplishes nothing. When one of us redeems himself, we are all stronger.”–p.324

About the Author

B.L. Blanchard is a graduate of the UC Davis creative writing honors program and was a writing fellow at Boston University School of Law. She is a lawyer and enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians. She is originally from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan but has lived in California for so long that she can no longer handle cold weather. She currently resides in San Diego with her husband and two daughters. The Peacekeeper is her debut novel.

—

The Peacekeeper was published on June 1, 2022 and is available for purchase online or in stores.

—

Note: The author of this review received a copy of the book in exchange for a free and honest review.

—

If you want to learn more about the plight of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and two spirit folks, I highly recommend going to https://mmiwusa.org/ and https://www.csvanw.org/mmiw/. If you’re into podcasts, I’d recommend starting with We Are Resilient and War Cry Podcast.

Images Courtesy of 47 North

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!