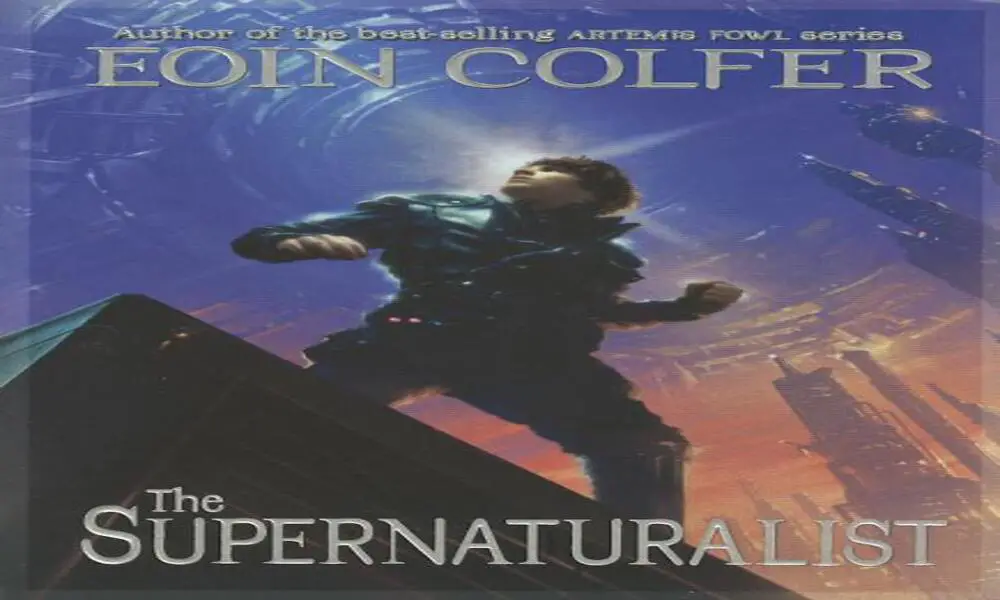

Remember The Supernaturalist?

Yeah, I didn’t either.

The 2004 novel popped out in the middle of author Eoin Colfer’s famous Artemis Fowl series, in the two year gap between The Eternity Code and (my personal favorite) The Opal Deception, with a graphic novel debuting in 2012. It was a bit of a welcome oddity, given the cliffhanger that Eternity Code had left us with: the character growth gained during the events of Eternity Code represented a major turning point and shift in the series that would have major ramifications throughout. As such The Supernaturalist comes across as something of an experimental novel as Colfer developed Fowl‘s next step.

And…it was a pretty good book. Whereas Artemis Fowl had a more futuristic fantasy theme, Colfer leaned heavily into the dystopian cyberpunk aesthetic for The Supernaturalist. Of course a lot of themes remained the same between the two: both featured a clever, if lonely, protagonist encountering a world usually unseen and developing a makeshift family-esque relationship with the people around him, all the while extolling the virtues of cleaning up and protecting the planet’s resources and life. Basically Spiderwick meets Bladerunner with a dash of Captain Planet.

So why am I talking about a lesser known YA novel almost twenty years after the fact? Because like many problems, it started with Disney.

Rather, it started with Disney’s…liberal interpretation of the aforementioned Artemis Fowl series as they released not only a 2020 direct-to-stream film under the same name, but also released several gallons of metaphorical wildfire all over long-time fan’s hopes, dreams, and faith. The movie was panned globally, by both old and new fans, who lambasted the film for its awkward CGI, cheesy dialogue, nonsensical plot and unwanted changes to the source material.

Now to be fair to Disney, it has been trying very hard, given its growing audience and medley of various acquisitions over the years, to retain its reputation as “child-friendly”. A story in which a narcissistic twelve-year-old genius kidnaps and imprisons a woman in order to ransom her for a ton of gold and her less than amused and pretty chauvinistic co-workers eventually settle on attempting to murder him and everyone he loves probably had a bit of trouble making it past the focus groups.

But Colfer’s legacy does not deserve a pretty awful cinematic to be the last exposure the general public has to it and so I submit The Supernaturalist for consideration.

Let’s meet our cast, shall we? We have Cosmo Hill, an orphan slash human guinea pig housed with dozens of others in the almost incredibly politically correct institution known as the Clarissa Frayne Institute for Parentally Challenged Boys. Stefan is the former police officer searching for answers about his mother’s death. Mona is the former member of an infamous auto gang and Ditto is a former science experiment of a government that tried to breed Captain America but ended up with Tyrion Lannister.

Now at its core, let’s be clear: The Supernaturalist, despite each of its characters bringing an impressive amount of baggage on board, has a rather by-the-numbers plot. You have your obligatory teenage puppy love between Cosmo and Mona. Of course, her character development is pretty waylaid by the second act to make room for romance and provide the audience a second look into the world at large—in other words, she’s pretty much the Bulma of the group.

(No, wait. The Chi-Chi of the group. Dragon Ball: Evolution Chi-Chi.)

Stefan is your standard tough guy (and let’s face it, the real protagonist) with a heart of gold who has an unfortunate case of tunnel vision and an obligatory third act temper tantrum over Ditto, who brings the wry humor and cynical wisdom to bear as the oldest and smartest of the lot and a your standard group-shattering secret regarding their “enemy”: the blue, life-force stealing entities unoriginally referred to as Parasites, who can only be seen by those who have been pulled back from the brink of death.

So yeah, none of this is new. But it can be.

As I mentioned, Disney took some unpopular liberties with their interpretation of Artemis Fowl, including a redesign of several characters. I’m not going to nitpick about it; it’s been done to death, from fans extolling book details to the comparison to the series’ graphic novel. But I am going to say something I rarely ever do: Disney was right and we should really do it again. Not about Artemis Fowl. No, that was a disgrace to my very childhood. No, I’m talking about redefining the past through a modern lens.

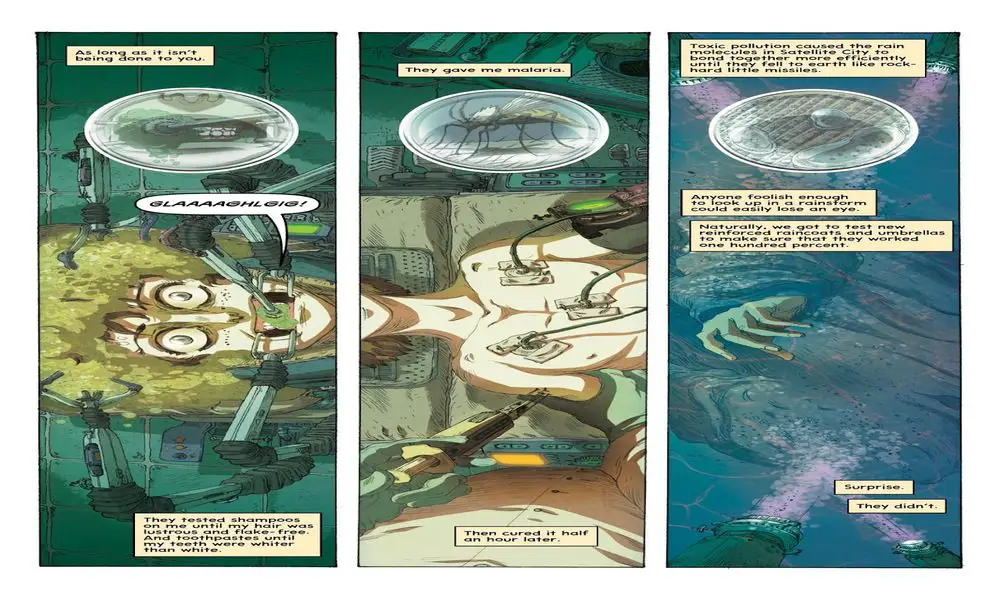

Everything about the treatment of the characters is indicative of modern school discrimination and police brutality. The boys at Cosmo’s orphanage are treated like literal lab rats, fed with the cheapest dregs of government-sponsored biddings, and emotionally abused and psychologically tormented. Those with special needs are considered disrespectful problem children. Armed guards watch their every move. Cosmo gives the reader a medley of detail regarding a specific type of torment liberally applied to the boys: a special type of gun that shoots cellophane wrapping and wraps about the victim so tightly, it can break ribs.

There’s an allegory for…a ton of stuff right slap dash at the start: The school to prison pipeline to start. As much as I love Into the Spiderverse, it does kind of skim over some of Miles’ more social anxieties in terms of background and race: the fact that his attendance to the prestigious Visions Academy is obtained via lottery, the social disparity we get a glimpse of as he leaves his passes his neighborhood high school with its industrial chain link fence. The very first chapter of The Supernaturalist features something of a prison break as Cosmo and his closest friend, a wisecracking ginger with a possible neurological disorder, are hunted down by their sadistic prison warden following a devastating car crash. These boys don’t have a future; none of them expect to live to adulthood.

And of course, the last half decade or so has really pushed forward the uncomfortable truths regarding police brutality and state-sponsored coverups and denial of such. Beyond the fact that we’re presented with kids being treated like criminals for matters they can’t control (where haven’t we seen that before?) we also are told, point blank, that orphanages blatantly fabricate criminal records for their wards in order to have them sent to prison camps once they’re old enough.

Am I saying that should cast Cosmo Hill as a POC? No, I’m not saying that. Then again, I’m also not not saying that this metaphorical movie should have a POC as the main character. As the years have shown, having a familiar face presenting familiar problems in such a way that everybody can understand can go over very well.

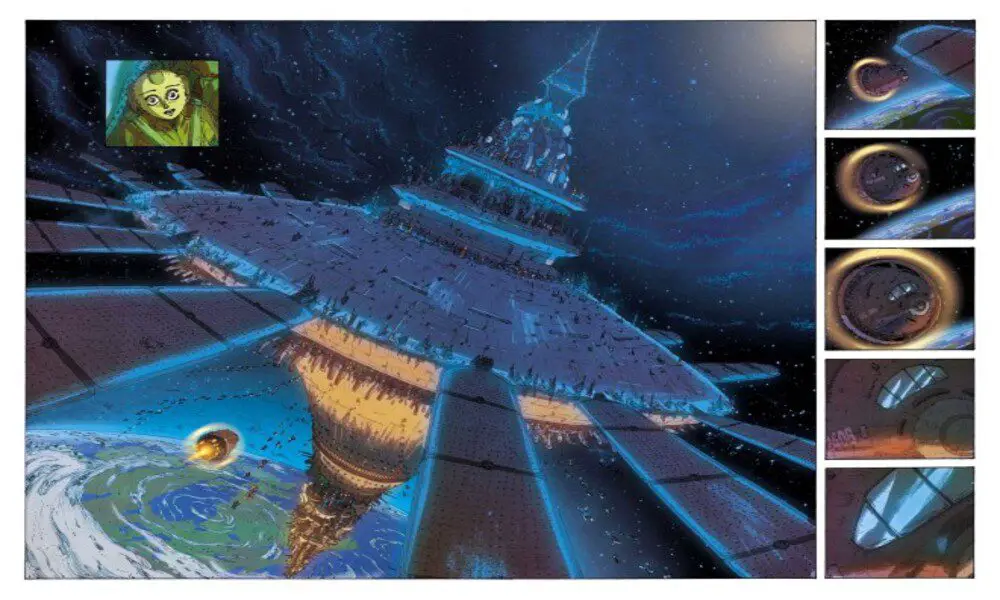

Beyond the sociopolitical turmoil, we of course have the theme of technological over-reliance and environmental abuse. That car crash I mentioned? It occurs because the overarching satellite that controls every technological aspect of the aptly named Satellite City glitches and not only does the orphanage prison bus lose its GPS, but neither the “driver” nor any other person on the road actually knows how to drive. The sunsets are described as being a vibrant purple, due to the sheer amount of chemicals and smog in the air. The City is facing an energy crisis, and the aforementioned satellite that basically runs the city is slowly falling out of the sky.

Furthermore, we’re seeing a resurgence of the cyberpunk aesthetic and environmental messaging in modern media. Cyberpunk: Edgerunners was a masterpiece of storytelling, atmosphere and animation. Behind the enemies to lovers trope of She-Ra and the Princesses of Power is an ever-present war between the beauty and power of nature and harsh industrialism and colonialistic exploitation.

From the get-go the novel develops a familiar battleground that CGI would absolutely love: the quintessential technocratic, corporate-oligarchical dystopia. Automated cars, faceless security, cyber-punk-esque, borderline-assassin lawyers, corporate espionage. The setting, fully fleshed out, could be absolutely gorgeous. And it doesn’t even have to be CGI! Animation has hit a new wave of experimentation, from the motion smearing comic-style of Spiderverse to the 2D/3D on and off texture push and pull of Arcane to the hand-drawn smoothness of Vox Machina. We have a thousand worlds developed through CGI but new horizons being discovered every day with a host of creative, innovative mediums.

2020 was bad enough without Eoin Colfer having his magnum opus be utterly besmirched on the metaphorical silver screen. And beyond that, let’s stop insulting kid’s intelligence? If you expect them to understand grief and honor and remembrance in Bridge to Terabithia, have faith that they can infer that kidnapping a elvin police officer and holding her for ransom is, in fact, bad. Disney has the opportunity to redeem themselves, Colfer, and the old and new generations in one fell swoop.

Then again, a movie about about people resisting the whims of corporate overlords and exploitation may not be the film Disney wants to make so maybe we won’t get that redemption arc after all.

Images Courtesy of Hyperion Books

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!