Once again technology, time as a construct, and the very universe itself have conspired to keep Thad and I from recording an episode of Beneath The Screen Of The Ultra-Critics. So we do what we always do in these situations: we make lists.

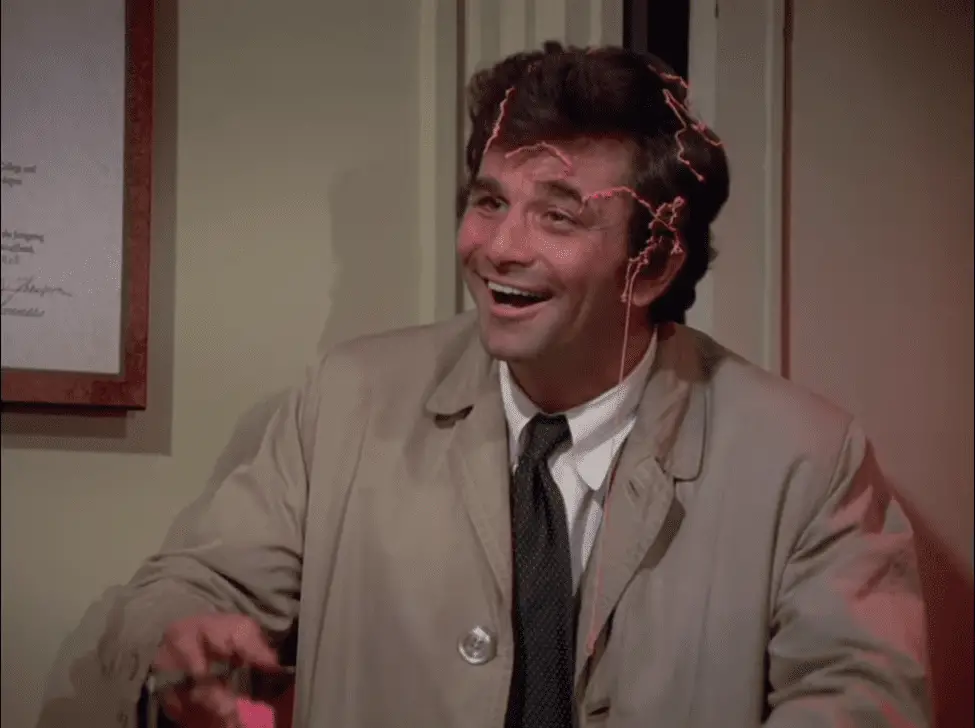

It’s well known that my life consists of movies and baseball; Thad’s being games and comics. But both of us share a deep abiding love for the long-running series of television movies, Columbo. The original Columbo was a made for television movie based on a popular play Perscription For Murder. It proved so popular NBC followed it up with another Columbo movie Ransom For A Dead Man. NBC then did something kind of odd. It launched a series of murder mystery shows that would air on Sunday but with different shows every Sunday. Columbo was the most popular due largely in part to Peter Falk’s portrayal as the loveable rumpled American answer to Hercules Poirot.

Falk’s Columbo is an oddity in the television landscape. He was the title character but he almost never showed up until at least the fifteen-minute mark. We never see him at home, or for that matter, almost never at the police station. He exists almost solely with the guest star of the episode, the murderer. We knew the guest star was the murderer not just because they were the guest star, but because Columbo would show us the murder.

It’s not about whodunnit or how. It’s about watching a duel of wits. Seeing how this guileless Los Angeles Homicide detective who wears a raincoat at all times is going to figure it out. It’s a mystery where the mystery isn’t the point. You know how it’s done and why. The question is how will Columbo figure it out?

Columbo as a character is a bizarre outlier when compared to the reams of other fictional detectives, both on television and in literature. What we mean by American Paradox is how the values Americans love to extoll about themselves are oddly lacking in most popular detective fiction. Except for Columbo.

1. The Curious Case Of The Happy Marriage

Thad: In large swaths of detective fiction, The Detective’s Family tends to be one of two things: non-existent or a plot engine. Either you fly solo, like Philip Marlowe, Sherlock Holmes (sort of), or Miss Marple or your family is some sort of machine that produces either personal trauma or complications that interfere with The Job or sometimes get kidnapped by sex criminals or whatever (my mother watched a lot of Law & Order SVU, but I never paid super-close attention so it kind of blurs together).

Conversely, our Lieutenant Columbo has a family. Wife, kid, extended relatives he mentions from time to time. And they’re not a drain or a drag, they’re simply part of his life. Just not the part that the show focuses on. And they’re not drawn into cases as kidnapped leverage or trying to pull him off cases. His family exists in the way that most families exist: naturalistically in the background. Not on intrusion, but part of life. And every time I circle back around to watching Columbo I’m reminded how weirdly rare that can be across fiction.

Jeremiah: Mrs. Columbo is the center of Columbo’s universe outside the job. We never see or hear her, much less know her name. Primarily this is because we only ever see Columbo at work and can we really blame him for not name dropping his wife to a murderer?

In “A Stitch in Crime” we see the Lieutenant show up beleaguered and exhausted from a sleepless night. His wife has been sick and he’s been taking care of her. What’s remarkable is he never complains about it. Oftentimes it’s talking with his wife that helps him solve the case, a fact that he never fails to mention to the murderer. “You know it was funny. I never thought about it, but my wife, she saw something on the news about it and we were talking over dinner…”

Some fans speculate that Mrs. Columbo is a myth—something made up by Columbo as a ruse. The theory is born from Falk sometimes wearing a wedding ring and sometimes not. I think this is clearly a case of people confusing real life with the character. For, if Mrs. Columbo doesn’t exist, then it strikes at the heart of why anyone loves Columbo in the first place: his kindness.

Now, you can play a fun game of “Which relative is nothing more than a cipher for Columbo’s sick burn?”. “Blueprint for Murder” has Columbo bringing up his cousin, who’s a lawyer, to contradict a suspect’s earlier statement and to subtly call him a liar. The murderer comes up with another lie to cover that one. But then pauses and says that Columbo’s family must be very happy with how his cousin turned out. Columbo can barely keep a straight face as he says, “Oh yes. We’re all really proud of him.”

2. A Study In Non-Toxic Masculinity

Thad: Famous ladies like the aforementioned Miss Marple or Jessica Fletcher notwithstanding, detection is traditionally A Man’s Game. A Hard Man’s Game. A Hard Man’s Game for Hard Men. There’s rage and violence, there’s chest-puffing and all manner of pissing contests, and there’s sex with dangerous women because how’s anyone gonna take you seriously as a Hard Man if you don’t have sex with the woman who probably paid to have somebody killed? It requires fearlessness and steel nerves and no distracting emotions getting in the way of Rough and also Hard Justice…

Sorry, I went a little too Frank Miller there. Toxic Masculinity is one of those phrases that piss people off due to reading it in the worst possible way: that is, claiming all masculinity is toxic. But that is, of course, not what it means. Toxic Masculinity in a broad sense means thinking all that stuff up there in the above paragraph are the important core attributes of being a man, and if you aren’t doing those things then you aren’t a Real Man. A Real Hard– stop it.

And here we’re back to Columbo, in all his Non-Toxic Masculine Glory. He has a job to do and is not interested in proving anything. Or rather, he’s not interested in proving anything outside of who committed the murder. He has confidence in his skills but isn’t afraid to admit not knowing things and asking for help or clarification, a trait that is so unexpected in the world of the show as to be almost universally disarming. And it’s rather unexpected in our own world, too. I suppose “A Man With Nothing to Prove” can sound like Toxic Masculinity, but it doesn’t have to have that aggressive sense to it. Look to Columbo! He has nothing to prove and it opens him up rather than closes him off.

Jeremiah: Columbo never goes around shouting and berating people. Even people he knows are guilty. But this is not to say he doesn’t get angry, it’s just rare and never in a sort of performative way. Falk portrays Columbo with a startling amount of humility and kindness.

His emotional maturity sets him apart from most fictional male heroes, not just detectives. Columbo is a bumfuzzled scatterbrain but he’s never mean or condescending. When his temper does flare up it’s always on behalf of other people. “A Stitch In Crime” has the infamous scene where Columbo slams a metronome on Leonard Nimoy’s desk after he laughs at Columbo. The Lieutenant isn’t mad he’s not being taken seriously. His anger comes from empathy and caring about human life. A life is in danger and he’s warning Nimoy that if he dies, Columbo will come after him.

“An Exercise in Fatality” shows Columbo exploding at Robert Conrad in the hospital waiting room. Conrad has driven the wife of a murdered man to attempt suicide. Columbo doesn’t just get angry; he calls Conrad on his lies.

A dog owner himself he all but demands medical attention for a dog who’s been trapped in a vault overnight in “Ashes to Ashes.” Over the chit-chat and crime scene banter, you can hear Columbo’s plaintive cries, “What about the dog? Somebody get this dog some water!”

He’s not above using the full forces of his badge but it’s never in a brash demanding way. “A Friend In Deed” has a scene where Columbo shows up at a suspect’s home and cuts to the chase. He’s direct, competent, but never in the man’s face. “Well, that makes sense.” Which is Colombo speak for, “Well, that’s some bull pucky.” Fascinating, to me, is that as Columbo leaves he shakes the man’s hands. It reminded me of Superman waving goodbye after he’s saved, someone. A small gesture that speaks volumes about a character’s inner life.

3. The Case of The Gentle Detective

Thad: The first thing Columbo does when he shows up in “Murder by the Book,” the first aired episode of the series, is usher the victim’s wife home after we’ve just watched her being rather callously questioned at the scene of her husband’s disappearance. He drives her home and cooks her an omelet. What other detectives would do that? Why aren’t there more heroes who, when they see a person in emotional pain, offer a hand, a kind ear, and tasty scrambled egg-based foods? Other detectives would be writing off the spouse’s emotionality or promising vengeance or whatever, but that’s not actually what moments of human pain call for. They call for kindness. And that’s Columbo. He’ll also bring the killer to justice, but that drive doesn’t steamroll the small moments.

Hell, he’s even kind to perpetrators (for the most part). Not berating them, not beating them up, often offering sympathy for their own pain in the final moments before the credits run. Because, as it happens, criminals are just people. They’re not problems to be solved or things to be caged, they’re just other people. And that’s a kind of outlook we need more of in the worlds both fictional and non.

Jeremiah: In the pantheon of American fictional detectives, the singular trait that rises above them all is a deep cynical pessimism. Columbo by comparisons could be viewed as the happy go lucky naif. In the episode “Try And Catch Me,” Columbo gives a speech.“I like my job. Oh yeah. Love it. I get to meet a lot of interesting people. And I don’t think everybody I meet is a murderer. Not at all. I think the world is filled with a lot of nice people, just like you folks.”

What permeates every fiber of Columbo’s being is his unfaltering belief in the goodness of people. It’s why he finds murder so repugnant and suicide so distressful. Amiable and good-natured, the Lieutenant is the rare detective who may be tired but always happy to be on the job.

He has a great empathy both for the murdered and the murderer. Despite the class war built within the show’s foundation, not every murderer is a horrible human being. “Sometimes I even respect them. Not for what they’ve done. NEVER for that. But for that part of them, that is clever, hard-working, funny, or kind. I think there’s kindness in everyone.”

Unlike most detectives, Columbo seems to view being a Homicide Detective as a holy calling. His kindness never interferes with his professionalism. When the murderer, played by Ruth Gordon, in “Try And Catch Me” comments on Columbo’s kindness he smiles, “Don’t count on that ma’am.”

In “Murder Under Glass,” Columbo cooks a meal with the murderer, a food critic. After Columbo catches the murderer trying to poison him, he explains how he knew he was guilty moments after meeting him. The murderer takes a bite of the dish Columbo has prepared and when asked how it is replies with, “Lieutenant, I wish you had been a chef.” The Lieutenant raises a glass and nods, “I understand, sir.”

4. Curiosity Killed the Cat But Caught the Killer

Thad: So I was just rewatching Season 3’s “Any Old Port in a Storm.” The murderer is Adrian Carsini, played by Donald Pleasence (a.k.a. Blofeld from You Only Live Twice, among other things). As the episode is winding down, having admitted his crime, Columbo is sharing a drink of some dessert wine in the car with Carsini before taking him to the station. And Carsini says, “You’ve learned very well, Lieutenant.” To which Columbo responds, “Thank you, sir. That’s the nicest thing anybody’s ever said to me.” This is not a sarcastic interaction. Columbo, as part of working the case, studied up on wine because it may (and did) turn out to be useful.

This, like all the entries, tie back around to not being a toxic ass. Being unafraid to look foolish—both honestly and as a ploy to press suspects—is core to how Columbo works cases throughout the series. Asking questions, listening, learning about things outside your sphere: good approaches to detective work in particular, but also to just being a good person. Yeah, so, maybe this has accidentally become a Columbo as Life Philosophy piece, but what’s wrong with that?

Jeremiah: Much like Sherlock Holmes, Columbo does his homework. Oftentimes, such as in “Double Exposure,” he will show up with piles of books in his hands. “You know I’ve been reading…” Partly this is done to ingratiate himself with the suspect. Sometimes reading the books they themselves have written, it is also done as a way to try and understand how the person ticks.

Columbo is fascinated by the modern world. “Double Feature” has a scene where a projectionist explains how the reel to reel system works as well as the theory behind subliminal editing to Columbo. The Lieutenant is riveted. Columbo’s suspects are frequently high powered businessmen of some sort but Columbo is interested in all aspects of the business. The passion of the elite such as in “Any Old Port In The Storm,” where Columbo becomes a wine aficionado. Or just the simple lives of the workaday people who keep the place running as apparent in every episode of Columbo ever.

Columbo can be a nuisance but it’s almost always upper-class people who find him to be irritating. But the other people Columbo talks with—the janitors, the maids, the secretaries, the gardeners—are kind of taken with him. He’ll comment on the job they’re doing, empathize with how hard it must be, and listen to their complaints or the pride they take in their work.

The Lieutenant is blissfully enchanted by modern technology. “Make Me A Perfect Murder” has an entire scene where Columbo just plays with the editing board in the editing room of a television station. His childlike curiosity at the world around him is what allows him to move with ease between the classes. The working classes see in him a friend while the upper class sees him as someone who is easily beguiled and inadvertently show their hand.

5. The Missing Gun

Thad: Guns aren’t needed for policing.

Look at most of the world as research on threat escalation mounts and it seems pretty obvious. Not in America, though, because everybody wants to be John McClain… and not even the good John McClain from Die Hard 1 and 3 and maybe 2 kind of (I’ve honestly forgotten). Hell, even Batman started out with a gun (being essentially a Shadow knockoff in his earliest days before code-enforced kid friendliness put an end to that). But Columbo doesn’t carry a gun (with few exceptions). He doesn’t like to hold them or even be anywhere near them in general. Guns represent an end that should be avoided at all costs. The real weapons against injustice are kindness and curiosity and empathy… connection to humanity. Basically anything other than that final disconnection there is no coming back from.

Columbo is the best, and he’s the best because he takes all these things that would be too often marked as flaws or weaknesses and just lives in them.

Jeremiah: Unlike every other detective and or policeman on television, Lt. Columbo never had a gun. It wasn’t just a character quirk either. It’s built into the DNA of the character.

Oftentimes when characters in a Columbo episode are in a firing range or showing off a gun, Columbo can be seen off to the side either plugging his ears or looking uninterested. “I keep it downtown,” he tells one character when asked by an Internal Affairs agent where his gun is. It’s less a political statement and more of a philosophical one.

Columbo seems to have a deep abiding hatred of murder. In “A Case of Immunity,” we see him wrestling with a coffee machine. As he complains to his superior about how the machine ate his change, he’s told there’s been a murder at a nearby consulate. Columbo’s rage vanishes as his eyes go wide, “Murder?” Coffee forgotten, he rushes to the scene.

His disgust or dislike of guns, doesn’t mean he doesn’t understand them. Oftentimes, such as in “Troubled Waters,” Columbo is keenly aware of how to handle a gun and how to extract evidence. He holds the gun in question with a handkerchief and with pencil shavings dusts the gun for fingerprints.

It’s a personal choice that is only ever broken in the late 90s when they began veering off script and adapting Ed McBain novels into Columbo episodes. Columbo himself philosophically, and to some extent morally, is against guns. Which makes him a stand out, with the possible exception being Jessica Fletcher. Which is, in all honesty, some great company to keep.