When Gandalf returned last chapter, he returned with a promise. A great storm was coming, he said, but he was returning at the turn of the tide. What this meant was left up in the air – perhaps his coming itself turned matters, perhaps the failures of Sauron’s and Saruman’s imaginations were shifting the balance. In “The King of the Golden Hall” we get another possibility. And as with most of Tolkien, it involves the universal – or even the cosmic – getting intertwined with the internal and personal. In the face of a vast war, a tide can turn simply by the individual choice to “dream no more”. To choose hope rather than the immense, glittering temptation of fear.

Things are not that simple, of course. We don’t all have the same set of choices. And so this is also the chapter in which we meet Éowyn.

Where Now the Horse and the Rider?

I love Rohan. It’s probably my favorite setting in all of Middle-earth (though in my more brooding moments, I have a soft spot for Lothlórien). It’s one of the few places that doesn’t feel ancient.

It is old, of course. It has a couple hundred years under its belt, and it has the true mark of age of any society: it’s started writing songs about its glorious past. But at the same time, there’s a freshness to Rohan. It’s due in part to its newness, in part to its repeated ties to the rolling green landscape that surrounds it, and in part due to its dependence on horses, which give it a sense of movement missing in much of the rest of Middle-earth. It also may simply be Tolkien’s contagious love for Anglo Saxon language and culture, a clear and heavy influence on Rohan.

I also find it so aesthetically lovely. Meduseld is a hall “filled with shadows and half-lights,” blue sky and sunbeams through the slats in the roof, rune-laden stone floors, carved pillars, tapestried walls. There always seems to be wind. There are always changes in weather rolling in across the plains like “seas of grass.” And, like the Ents, they even have a language to match. Legolas describes it as “like to this land itself; rich and rolling in part, and else hard and stern as the mountains.” And this is Tolkien, so it’s probably fair to also read this as “beautiful, like English before the French showed up and ruined it.”

Rohan is immediately likeable. But there’s also something immediately wrong. Rohan is turning in on itself: closing gates, limiting patrols, refusing to speak to anyone who doesn’t know their tongue. It’s a culture that’s drying out and dying in an attempt at self-preservation.

The Time for Fear is Passed

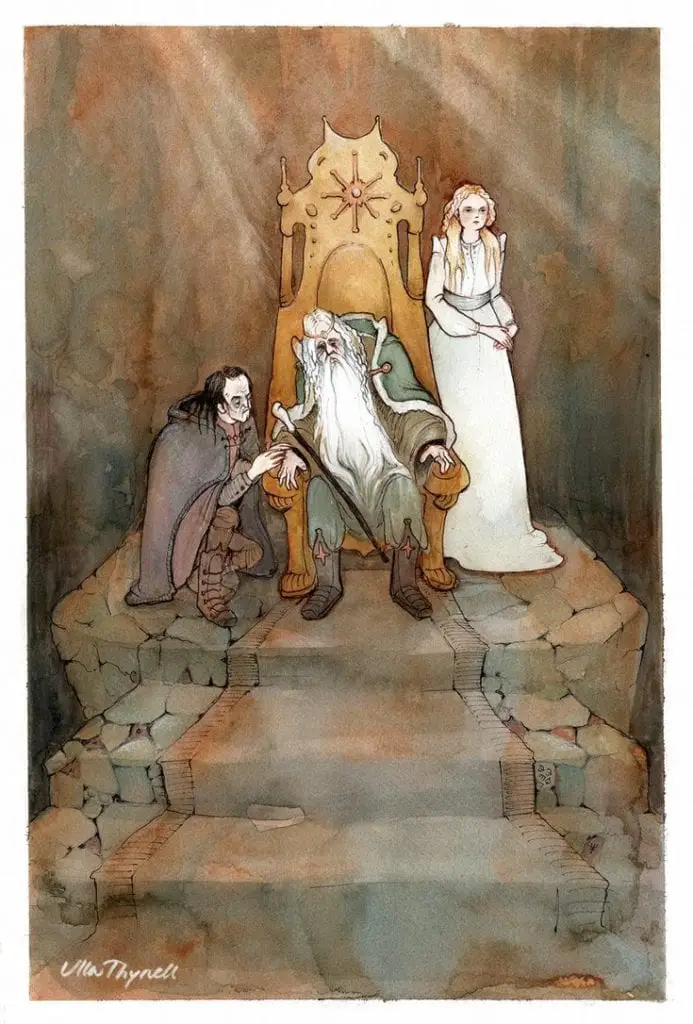

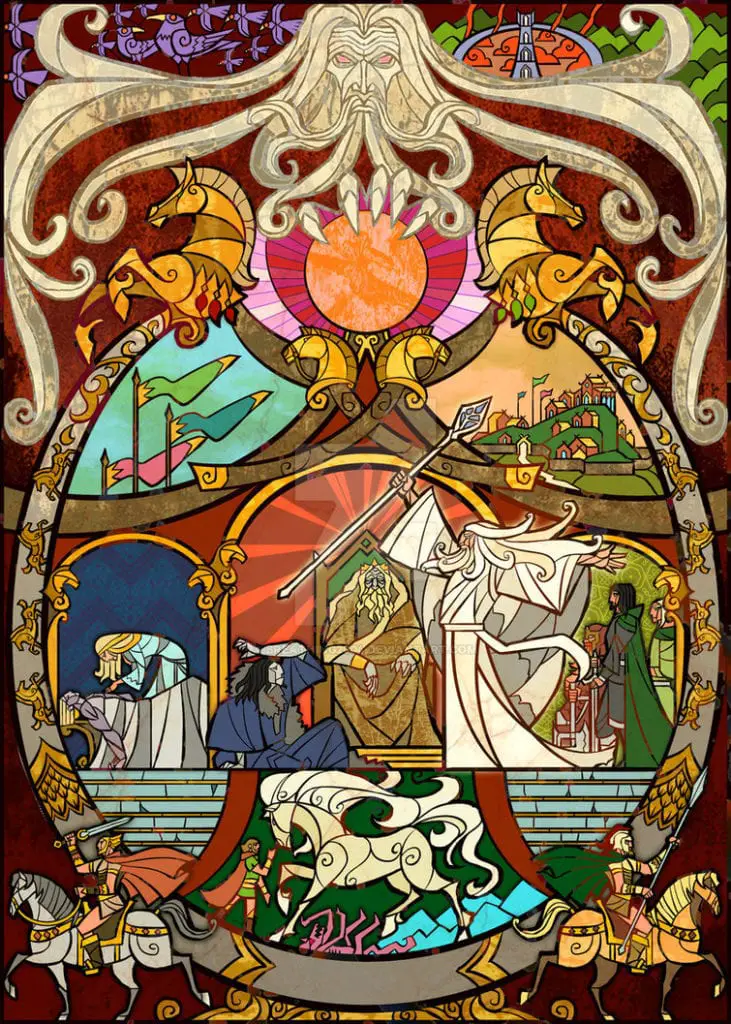

The center of Rohan’s ailments, it’s soon revealed, is Théoden. Old and frail before his time, he’s fed largely on a diet of whispers and conspiracies from his long-time advisor Gríma Wormtongue. Gríma is ramping up the old king’s fear – insisting that Éomer is out to betray him, that danger is ever encroaching, and that the only hope is to batten down the hatches and huddle away from the storm.

Gandalf, in an understated but somewhat exhilarating scene, brings him outside.

“Take courage, Lord of the Mark; for better help you will not find. No counsel have I to give to those that despair. Yet counsel I could give, and words I could speak to you. Will you hear them? They are not for all ears. I bid you come out before your doors and look abroad. Too long have you sat in shadows and trusted to twisted tales and crooked promptings.”

Slowly Théoden left his chair. A faint light grew in the hall again. The woman hastened to the king’s side, taking his arm, and with faltering steps the old man came down from the dais and paced softly through the hall. Wormtongue remained lying on the floor. They came to the doors and Gandalf knocked.

“Open,” he cried. “The Lord of the Mark comes forth!”

The doors rolled back and a keen air came whistling in. A wind was blowing on the hill.

“Send your guards down to the stairs’ foot,” said Gandalf. “And you, lady, leave him a while with me. I will care for him.”

“Go, Éowyn, sister-daughter!” said the old king. “The time for fear is passed.”

It’s a fascinating scene to me, in large part because it’s never entirely clear what happened. The extent to which Théoden was “enchanted” by Saruman through Gríma, and the extent to which he was “healed” by Gandalf is left intentionally ambiguous. It’s entirely possible to understand Gríma’s influence as the long-term effect of persistent, calculated manipulation. The appendices do mention “the spells of Saruman,” indicating the possibility of some type of direct magic (given what we know of Saruman, it is something he’d be capable of doing). But the extent of any magic is left very much up in the air.

The same goes for Gandalf’s “healing” of the king. There’s certainly some magic at work. The sky turns from blue to a dark-grey thunderstorm at a moment’s notice (too quick even for grassland weather systems!). Théoden’s wrinkles melt away when he smiles. Gandalf plays with the light and darkness within Meduseld to emphasize all his points. But still, there is such an emphasis of choice in Gandalf’s words. He doesn’t simply “heal” Théoden, he gives him the option to help himself be healed. And Théoden is repeatedly tested on it. Later in the chapter, he sits and trends back towards despair “as if weariness still struggled to master him.”

The same goes for Gandalf’s “healing” of the king. There’s certainly some magic at work. The sky turns from blue to a dark-grey thunderstorm at a moment’s notice (too quick even for grassland weather systems!). Théoden’s wrinkles melt away when he smiles. Gandalf plays with the light and darkness within Meduseld to emphasize all his points. But still, there is such an emphasis of choice in Gandalf’s words. He doesn’t simply “heal” Théoden, he gives him the option to help himself be healed. And Théoden is repeatedly tested on it. Later in the chapter, he sits and trends back towards despair “as if weariness still struggled to master him.”

Théoden’s recovery, magical or not, is the choice of hope over fear. As Gandalf, said, there’s nothing he can do for those who despair. And it makes this chapter so much more interesting and so much more in keeping with the trends of Lord of the Rings so far. Théoden isn’t just a pawn bounced around between the magicking of two wizards. He’s an individual making a personal choice, which will have long-reverberating ramifications.

Éowyn, Lady of Rohan

Théoden, of course, is in the position to make a choice. He is head of his house. He is the lord of Meduseld and the leader of the Rohirrim. And choices have been allotted to nearly all of our characters so far. From the powerful to the powerless, choice has been key to Tolkien’s narrative. It’s what holds the moral fabric of the story together.

Éowyn, when we first meet her, is relatively choice-less. Her country is in trouble, threatened from within and without. Her cousin, and heir to the throne, has died. Éomer, her brother, was imprisoned. Her uncle and father-figure is weakening, held in thrall to the isolationist advice of a man who creeps on her in his spare time. After several chapters of people overwhelmed by the number of choices with which they are faced, we come to Éowyn, who has almost none.

One of the first things apparent about Éowyn is that she is so sad, and so lonely.

The woman turned and went slowly into the house. As she passed the doors she turned and glanced back. Grave and thoughtful was her glance, as she looked on the king with cool pity in her eyes. Very fair was her face, and her long hair was like a river of gold. Slender and tall she was in her white robe girt with silver; but strong she seemed and stern as steel, a daughter of kings. Thus Aragorn for the first time in the full light of day beheld Éowyn, lady of Rohan, and thought her fair, fair and cold, like a morning of pale spring that is not yet come to womanhood.

Throughout her first appearance, Éowyn is described as cold, steely, and alone. It’s a nuanced and immediately interesting introduction. No one in the story so far is described in quite the same way. Éowyn is cold, but never cruel (adjectives that often come conjoined when describing women in fiction), widely loved by the people of Rohan. She is unquestionably strong, “stern as steel,” but never falls into the Not-Like-Other-Women trope. She is sad and somewhat bitter, and the narrative so far only allots her empathy and respect. The men around Éowyn respect her – no one hesitates to make her “as lord to the Eorlingas” when the men are off at war – but we’ll find out later that they also don’t listen to her.

It’s just *such* a good introduction. I love Éowyn a lot, as I’m sure you all have noticed. I have a quote about her engraved in wood hanging on my wall. So I’m biased. But considering that this is a chapter in which she only appears on the margins, I think she makes such an interesting impact on the story.

Unlike Galadriel, she doesn’t have a spotlight chapter and everyone’s immediate, undivided attention. She’s been suffering silently on the edge of the story. She spoken about and observed more than spoken to. Gandalf and Company sweep in – with that Ranger from the North looking awfully handsome and not-related-to-her – and apparently solve all her problems. But then they sweep out, leave her behind without a second thought, and leave her much as she was before. Éowyn watches the host move out and sees the glitter of their spears “as she stood still alone before the doors of the silent house.”

Éowyn is just the best. I’m so glad that she’s finally in the story.

Final Comments

- It’s an interesting chapter for Aragorn. His tentativeness from earlier in The Two Towers has largely evaporated and he doesn’t skip a beat in pulling rank when poor Háma has the audacity to tell him to leave Andruil outside. Háma, always delightful, doesn’t back down.“It is not clear to me that the will of Théoden son of Thengel, even though he be lord of the Mark, should prevail over the will of Aragorn son of Arathorn, Elendil’s heir of Gondor.” “This is the house of Théodon, not of Aragorn, even were he king of Gondor in the seat of Denethor,” said Háma, stepping swiftly before the doors and barring the way. It’s a fun little exchange, in part because they’re appealing to different authorities. Notice that Aragorn is appealing to Elendil, Háma is referencing Denethor. It’s a neat little note about the potential difficulties in succession that Fyodor suggested in the comments back in “The Departure of Boromir.”

- Aragorn’s prickliness continues when Háma wins the day.“I command you not to touch it, nor permit any other to lay hand on it. In this Elvish sheath dwells the Blade that was Broken and has been made again. Telchar first wrought it in the depths of time. Death shall come to any man that draws Elendil’s sword save Elendil himself.” The guard stepped back and looked with amazement on Aragorn. “It seems as if you are come on the wings of song out of the forgotten days.” I know that Háma is impressed by this. I know he is. But I will never, ever read this line as anything but Snarky Háma just dumping sarcasm all over Aragorn. It seems as if you are come *on the wings of song* out of the forgotten days!

- Gimli continues his trend of threatening to murder every new person he meets who dares to look askance at Legolas, Aragorn, or the mention of Galadriel. But if the trend continues as is, he and Háma will be best friends soon! Already Gimli has accepted an offer to ride side by side with former-enemy Éomer, despite decapitation threats thrown around only two days earlier. He accepts on the condition that his other best frenemy Legolas can ride on the other side. Oh, Gimli!

- I feel bad, but there’s a part of me that’s almost impressed by Gríma-influenced-Théoden’s greeting to Gandalf. It’s so bluntly antagonistic: “You have ever been a herald of woe. Troubles follow you like crows, and ever the oftener the worse. I will not deceive you: when I heard Shadowfax had come back rider-less, I rejoiced at the return of the horse, but still more at the lack of rider; and when Éomer brought the tiding that you had gone at last to your long home, I did not mourn.”

- Gandalf’s retort to Gríma a little later on is almost as good. “Be silent and keep your forked tongue behind your teeth. I have not passed through fire and death to bandy crooked words with a serving-man till the lightning falls.”

- I’d be curious to hear what everyone thought about the decision to let Grimá go. On one hand, it seems thematically on-point. On the other, it seems like a risky choice.

- While looking up something for this article, I came across the knowledge that Gríma / Saruman slash fic exists? I’m not sure why I’m surprised, really. Do with that information what you will!

- Prose Prize: “From the porch upon the top of the high terrace they could see beyond the stream the green fields of Rohan fading into distant grey. Curtains of windblown rain were slanting down. The sky above and to the west was still dark with thunder, and lightning far away flickered among the tops of the hidden hills.” This is in many ways a *metaphor storm* but at the same time I love Tolkien’s description. Maybe because thunderstorm season is approaching here in St. Louis, but it captures the sense of sitting under cover and watching a storm roll in.

- Contemporary to this chapter: As Gandalf & Company reach Edoras, Frodo and Sam make their way out of the far end of the Dead Marshes. By the afternoon, as the Rohirrim set off, the Entmoot comes to an end in Fangorn.