In my restless dreams, I see that town, Twin Peaks. You promised me you’d take me there again someday. And what do you know, you made good on that promise, David.

Using Mary’s Letter from Silent Hill 2 is not gratuitous for the sake of this introduction. If the pop culture imaginarium is a pond, the brainchild of David Lynch and Mark Frost was certainly one of the biggest pebbles. The ripples cast by this series were such that even now we feel the waters shaking. Be it through animated series, video games, music or film, the homage to Twin Peaks still goes strong. For my generation, this homage was often subtle, nigh imperceptible until we braved the oddity to experience it ourselves. Its subversive delivery, haunting plot, dissonance between tones, and themes both harrowing and captivating leave an aftertaste seldom equaled. Detective stories never grow old, but none ring quite like Twin Peaks. If you click on my name, you’ll see the mark’s depth through my reviews on the first season, airing through the spring of 1990.

Thus unfolded the story of Laura Palmer’s murder in the peaceful, frontier town of Twin Peaks.

A well-earned reputation

Nothing is perfect. Few works of art and/or entertainment via fiction are without flaw in execution or inner coherence. Some faults are glaringly obvious, while others are competently concealed or incredibly conspicuous. Having said this, Twin Peaks’ Season 1 is exemplary in the extension of one trope, that of the Chekhov’s Gun. All plots and subplots serve a purpose. All characters shoulder the bulwark of the main conflict to varying extents. Even those dwelling in obscure scenarios, unrelated to Miss Palmer’s death, served to feed the atmosphere that facilitated the crime. Everything mattered, and the viewer could not dismiss anything as trivial. By the end of the season, the tally was as follows. There was a prime suspect to Laura Palmer’s murder, devious parties schemed to burn the local mill, the drug and sex trades plagued the youth of the town, and a strange presence lurked in the shadows.

All storylines would converge at some point. And there could be no solution to the murder without some light on the rest. Simply put, all stories would grow and extend organically towards the season’s climax. And what did we get? A cliffhanger with a tri-partite effect. It shocked the viewership with the apparent killing of the protagonist. It shed further doubt on the mystery. And it functioned as a confirmation that there was still much more behind Laura Palmer’s murder. Surely, the second season would deliver resolution with a vengeance. Given how engaging this first season was, one could be forgiven for thinking all would be swell. Right?

I welcome an echo, a shudder, a cough, or a tumbleweed that always finds its way in when needed.

A sour taste

I recommend this series to everybody I know. I personally vouch for its quality and uniqueness. Nonetheless, this recommendation always comes with a warning, which sometimes feels like a justification. In layman’s terms, it’s addressing the elephant in the room. Whereas the first season was constant in quality, the second one took a considerable dive halfway through. At this stage, the series seemed to gravitate further away from the still unsolved mystery. This ‘middle-season funny farm’, as I’ve taken to calling it, can be described with a variety of adjectives. Tedious. Peculiar. Awkward. Because of it, the audience decreased significantly, leading to the series’ cancellation.

Several factors went into this strange development, both in narrative and outside of it. The importance of observing these stumbles is paramount when you’re tempted to call Twin Peaks’ Season 2 a waste of time. Despite interest waning around the series, the book ends were a faithful reprisal of that je ne sais quoi that had once captivated the audiences. Simply put, you cannot look at the bad without looking at the good. And here, at The Fandomentals, we’ll observe them through the what, the who, the how, and the why. Plus, if Agent Dale Cooper has taught us anything, and he’s taught us aplenty, is that everything matters.

For the following three weeks, we’ll enter the town of Twin Peaks from different perspectives. We will gain understanding on why the series still deserves its renown, loyalty, and fascination in spite of its shortcomings. We will analyze the prequel movie.

And above all, we’ll know why we should await Season 3 with bated breath and lots of coffee and donuts. I’m a firm believer in ending things on a high note, so we’ll start this triad of analysis with the bad. It’s always best to get the dirt out of the way in order to appreciate a work of art that shines golden beneath the dust.

Naturally, there will be spoilers ahead. You have been warned.

The Dance of the Bad Angles

Forever Young

Before we get down and dirty, I need to make something clear. There is an unspoken fact in fandom: mileage may always vary. The irony about such an objective assessment of the prominence of subjectivity is not lost on anybody, I’m sure. Essentially, reception on anything is prone to diversity; some may enjoy what others dismiss as rubbish. Therefore, the following paragraphs stem from both a consensus on the series’ dip in quality and personal opinion. I mean no offense on anybody who has enjoyed the moments to be dissected here, in spite of my very colorful phrasing.

All appropriate things soberly said, it’s time to open with a blast, the first issue at hand. Whereas Laura Palmer’s murder carried the whole of Season 1, Season 2 solved the mystery and not even halfway into the season. This fact alone already hurts the show’s pacing, forcing the sense of conflict to migrate or disperse.

Bobby Briggs wasn’t wrong when he spoke at Laura’s funeral. Virtually everybody okayed the circumstances that led to the young woman’s death. Only one did the malicious deed, but all residents played a part. This makes for a very cohesive narrative, to which all side-plots appear as another distinctive facet. Yet, solving Laura’s murder this early means compromising the strength of Season 1 in favor of something else. The ensuing plot must absolutely be an even greater conflict to make up for the figurative balloon deflating.

Did we get that greater-scope conflict? Yes, we did. But it took a pretty long to get there. In the meantime, we got wacky, tone-breaking shenanigans.

Let’s start with Nadine after coming out of her coma. Back in Season 1, she was somewhat of an unstable character. She had an obsession centered on a goal which several, if not many, would deem trivial. Her interactions with her husband, Big Ed. often rang sour. She appeared to play an obvious foil to fair Norma in the star-crossed narrative between she and Ed. However, Nadine’s failures in patenting her soundless drape runners brought something true and relatable out of her. Behind the fury, she was a woman troubled by insecurities and fears. Her marriage to Ed was the sturdiest rock she had, but it didn’t suffice, as she ruefully attempted suicide by overdosing on pills. This effectively buried any relationship between Ed and Norma for the sake of sheer humaneness. Above all, it made the viewership care for her welfare and at least some joy in her life.

As a respite from despair in a town already well sunken in it, Nadine survived. Rather than breaking another heart, she remained bedridden in a coma for three episodes. In typically uncanny Twin Peaks fashion, her mental state was significantly different from her usual persona. Lo and behold, Nadine thought she was an eighteen-year-old high school student! Oh, and she also had super strength, as you do. Now, don’t get me wrong; I think this was a rather enjoyable development. Not everything could be dark and dreary. (As we’ll see next week, there was plenty of that.) Nadine as a spry and strong young woman at heart was not bad in itself. But much like somebody with super strength proper, her surroundings suffered the damage. Instead of collapsed infrastructure a la Hulk Smash, Big Ed and Mike Nelson ended up a ruinous mess.

We could summarise the angle through a shift of interest from Big Ed to, of all people, Douchebag Mike. In the process, both characters lost plenty of significance. Whereas the former had several things going for his character before, he was reduced to his relationship with Norma. There was hardly any further focus on him as one of the Bookhouse Boys, thus losing that bit of mystique. Furthermore, this new state of affairs allowed him to pursue a legitimate relationship with Norma. But herein lies the problem: it felt too convenient. There was no payoff to this turn as the parties involved felt as if they were an afterthought from the writers.

It simply didn’t feel deserved, and neither did Nadine’s shift of affection towards Mike. Nearly all of his villainy faded without a reason, just to humorously become Nadine’s initially unwilling high school crush. He was turned into a hollow character, an accessory, towards a dead end. Although, let’s be honest. You could say Mike’s very role was a red herring in Laura’s murder and a foil to make James look better. Nonetheless, the final effect of his returning Nadine’s affections felt just as bland. And yet, speaking of James…

Sad to the Bone

Laura Palmer’s secret boyfriend arguably never served much of a purpose, even in Season 1. He got to hang around with the Bookhouse Boys a bit. He also partook of a Scooby Doo-like scheme to root out some truth from a plausible suspect. Mostly, he just rode on his bike. Rather than attributing his character to poor writing, it would be fair to say he was precisely what he was: an adolescent. As a son of unfit parents, he was always going to be somewhat troubled. Perhaps his bike was really an analogy for his seemingly eternal search for self. Perhaps the errant vascillation of his affections between Laura, Donna and Maddy were a channelling of an inner hollow, wanting to be whole.

Whichever way we read the character, one thing is clear: the execution was problematic. You only need to look at his expression upon hearing the news of Laura’s death to know something is up.

It’s also not accurate to dismiss the entire bulk of James Marshall’s performance as bad. After all, he functioned serviceably towards other narrative lines. The problem came when he got his own on Season 2. And here is something that annoys quite a bit. It could have been actually good, since there was quite a rich context leading up to it.

As we’ll see in the film’s analysis, his relationship with Laura was eventful. It wasn’t pretty, but it was not an affair that heals seamlessly. Maddy’s arrival in town reopened the old wound on his heart through her striking resemblance to her cousin, Laura. However, unlike late Miss Palmer, Maddy’s personality was more transparent. She never underwent the heinous things Laura had endured throughout her life. Thus, we could describe her as ‘wholesome’. These two factors led to some attraction from James, who couldn’t help but see Laura in her. This development is basically a fray between past and present, a conscious and painful healing process. Ultimately, she and James had a bittersweet farewell. Little did anyone know, she’d soon be murdered by the same man who killed Laura. Her demise ultimately sent James into a soul-searching ride out of Twin Peaks.

Let’s take a step back and observe a major working ‘Lynchpin’. Throughout David Lynch’s work, we can see duality as a constant motif. The diametrical opposition of characters around an axis always has a vital storytelling function. In the overall scheme of Twin Peaks, we can read this particular Laura/Maddy duality as a relation of damage and innocence. This bears consistent importance, given how several characters, such as Bobby or Audrey, constantly navigate this relation. In the dreadful moment when both extremes meet a grisly end at Leland’s hands (as BOB), James becomes an heir to the duality. His ride away from town becomes a necessity. This could have been a shining moment for James.

Instead, he simply ended up in a shady relationship with a married woman called Evelyn Marsh. In truth, she was using him, in cahoots with her lover, Malcolm. In the end, James would be incriminated for the husband’s death while Evelyn and Malcolm rode into the sunset, in an evil way. However, things would turn out differently through the POWER OF LOVE (caps intended to sell the effect). Evelyn’s feelings towards James turned out to be legitimate, which prompted her to shoot Malcolm dead when he was about to kill James. Although the overall effect of this arc may be the whole ‘love redeems’ gig, its delivery felt flat. Although Twin Peaks was an exercise in genre-subversion, this soap opera-ish angle lacked the slightest satisfaction. It’s even hard to explain it as a parody of the genre.

The ultimate payoff to this plotline was that James once again rode off into the sunset. It’s never a good sign when Facebook shitposting groups have the right about something. James was reduced to being sad and wanting to hop on his bike and just go away. Oh, and Donna was involved too, in the end. But, at this point, nobody really cared about her. This is entirely subjective on my part, but Donna and James really shone brightest when hanging out with Maddy. Her death, one of the most tragic and amazing moments of the series, virtually killed off the other two’s relevance. A damned shame, if you ask me.

Villainous Decay

One of my favourite things in life is villainy. I don’t condone foul deeds or perform them (I did steal a pizza once, though). However, in fiction, an effective villain can redeem a lot of bullshit. Thus, I tend to be rather lenient about some characters’ delivery, if their backstory or motivations are sound. Leaving aside the greater scope of villain on Twin Peaks, I’d say there are two main baddies in both seasons, respectively. Season 1 got Leo (Mr. Plausibility). He was detestable and menacing, and loved being a dick. The beauty is in its simplicity. Season 2 got Windom Earle, and he was just creepy, even goofy. He did have motivations behind his vendetta against protagonist Dale Cooper. But overall, his performance is a mixed bag.

This is not to say he didn’t have some shining moments. He did use some neat cryptic shit to ensnare Cooper into his ‘retribution’. He also ended up a suitable bit of a mini boss to Twin Peaks’ ‘final boss’. So, even if Windom came off as more of a Bizarro than a Luthor, Cooper now had an enemy proper. Not only would he target Dale where it hurt, he would also draw our hero into the dark endgame.

So, all in all, Windom Earle himself is not entirely a rough edge. However, his absurd antics with Leo Johnson are pretty shit, He basically turned Mr. Plausibility into the world’s saddest pawn. The effect of this is also pretty fruitless, and served no purpose other than ‘redeeming’ Leo. If we stop to consider all the awful things he has done, this is unwarranted.

We could see Leo’s wheelchair-bound state as a sort of poetic justice. Shelly and Bobby were not entirely innocent characters either, but the moral distinction is clear. By the logic of cause and consequence in narrative, the constant ridicule had to reach a boiling point. Thus, when it did, we got a legitimately frightening moment straight out of a slasher flick. Leo, no longer paralysed, regained his fangs and haunted Shelly like a feral predator – with an axe. The well-timed intervention of Bobby helped avert the crisis. So, away Leo fucked off, hindered but not defeated. Then Windom Earle got his hands on him, turning the baddie into a quivering little minion. Hell of a way to dull the edge out of a recently unsheathed blade. This begs the question, was this sacrifice of a character worth it? Yes and no, but mostly no.

The more evident goal of Leo’s decay was building Windom as a greater evil than Leo ever was. Destroying Mr. Plausibility’s momentum at rising from his wheelchair undermines his thirst for vengeance against Shelly and Leo in favor of the GREATER GOOD… I mean, greater evil through Earle’s scheming. However, given the tasks the new baddie had Leo do, this ‘recruiting’ feels rather unnecessary.

Furthermore, most of the time we got to see Leo, he was being tortured or abused in one way or another. In the end, he met a likely demise via tarantulas. But the ‘heroic sacrifice’ involved becomes meaningless when it comes to a character the audience probably stopped caring about long ago. His relevance had been shed away, one episode at a time.

Truly, both Windom and Leo could have benefitted from acting independently of each other. This would have made Cooper’s nemesis no less of a threat, and would seize upon Leo’s perennial bloodlust and hatred. It’s also thematically sound given the essentialisms of good and evil in this season (We’ll look at this next week). Having two agents of that darkness might have given some urgency or direness to a pretty unengaging mid-season.

Gods know there were plenty of other subplots that could have done with a little more ‘edge’. These subplots aren’t necessarily bad; in fact, I’d even call them rather enjoyable. Sure, Audrey falling for Billy Zane after Cooper had set such a high bar for all men in her life is kind of weird. All in all, if not overly inspired, they were harmless.

On the other hand, the examples mentioned above dragged on too long to disappear into the background. They demanded the viewer’s attention, and in turn weakened the viewer’s interest. Wacky at the least, and wasteful at worst, we end up with one question in our tongues. Who is to blame?

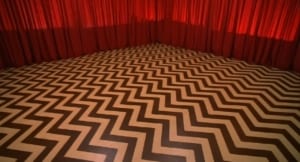

Behind the Red Curtains

A few nights ago, I was talking to my friend Jorge (whose articles are the bees’ knees) about TV series. Firefly often comes up, and we all know the terrible fate it met. It was a virtually flawless series, and it ended too soon. Some say this could serve as a cautionary tale on expectations when tasting magnificence. Others would say it’s more of a cautionary tale on the caprices of network executives. Both ends are applicable to Twin Peaks, in fact. Prior to airing, the show’s production met with resistance from ABC executives. It’s your average case of unorthodox gig the suits have little faith in. Nonetheless, with the support of Robert Iger, the show got its chance. Yet, the corporate overlord shadow (pardon the cliché) likely never stopped hanging over the creators’ heads.

The haunting mystery and the nuanced character development arcs made this first season an unexpected success. However, it may have been this lovely turn of events that prompted the decision to make the second season twice as long. From what we can see above, many of the narrative problems stem from one issue, pacing. In spite of the complexity of each character arc, the main driving force was the mystery of Laura’s murder. The characters’ narratives still gravitated toward this event as a catalyst. But here comes a peculiar twist outside of the narrative. The creators’ intention was for the murder to fade in the distance in favor of the character arcs. This is a stark contrast to the executives’ alleged intention of solving the murder back in Season 1.

Thus, we can extrapolate here a sort of cruel irony. The final product in Season 2 ended up quite faithful to this intended scheme. With Laura’s murder solved, the focus migrated to the other characters. But what we got was not precisely remarkable, at least not in a good way. The creators possibly became slightly disenfranchised with the series, judging by Lynch and Frost’s absence at the helm throughout the driest spell in Season 2. Still, in face of the poor state of the series, the creators acknowledged the error of solving Laura’s murder too early. That’s a plus. And in the final episode, they returned to make a season finale for the ages. That’s another plus. It’s one swerve after another with these two. Unfortunately, the series failed to snatch back the public’s interest as the show’s time slot was changed. Thanks a lot, Gulf War.

Thus, the series was cancelled.

In spite of the network’s final decision to pull the plug, the series’ influence remained strong. Its ambience, motifs and even life codes became so engraved in a generation’s collective mind that even now we get distant echoes through homage. The obsession with the forces drawing breath beneath the soil and the unknown fate of FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper have enraptured the imagination of so many.

And now, more than 25 years later, we’ll get closure. The sins are forgiven, and the voices of the executives are now but a lowly murmur in the background. Next week, we’ll see the reason for the fanbase’s loyalty. Every time I recommend this series, I warn that Season Two 2 wonky halfway through, but I always end my recommendation with the same words.

The good far outweighs the bad.

Stay tuned, lovelies.