- Warrior Nun Struggles As a Trauma Narrative (Part 1)

- Warrior Nun Struggles As a Trauma Narrative (Part 2)

- Warrior Nun Struggles As a Trauma Narrative (Part 3)

- Warrior Nun Struggles As a Trauma Narrative (Part 4)

- Warrior Nun Struggles As a Trauma Narrative (Part 5)

Content warning: discussions of child abuse

Spoiler Warning for Warrior Nun

Introduction:

This July Netflix released Warrior Nun, a fantasy action drama that has converted our site to its cause. Showrunner Simon Berry loosely adapted a ’90s comic book series, Warrior Nun Araela, and transformed a misogynistic property whose costume designs made me want to cry into a fun, feminist property. From charming characters to clever worldbuilding, the show provides a necessary escape from our hellish reality, and supports a diverse cast of women and people of color, as well as female queerness.

The story follows Ava Silva as a nineteen-year-old orphan who comes back from the dead and discovers she has superpowers. She can also walk for the first time in twelve years, having been paralyzed from the neck down after surviving a car accident that took her mother. With her powers, she can heal herself and phase through solid objects, and she can also see the low-level demons, called Wraiths, that feed off the darker sides of humanity. But what intrigues Ava the most is her newfound mobility — literally and figuratively. Ava Silva embodies joie de vivre, and that buoyancy of spirit drives the show. And that light contrasts against her backstory as an orphan subjected to abuse from Sister Francis, the nun who verbally degraded Ava while caring for the bedridden girl at St. Michael’s Orphanage.

Soon enough, an ancient order of militant nuns, the Order of the Cruciform Sword (OCS), seeks Ava out because her superpowers come from an angel’s halo which they had guarded for centuries. (A nun placed the halo in Ava’s back in order to hide it, as Ava was a convenient corpse in the morgue, but the halo resurrected her instead.) The OCS has several key members who eventually become Ava’s found family: Shotgun Mary, Sister Beatrice, Sister Camila, and Sister Lilith. For the first half of the season, Ava is either running away from the OCS and trying to find some sense of normalcy with her crush, or having to endure guilt trips and abuse from the organization. Ava ruffles their habits and refuses to trust any nun during the first six episodes, as the OCS too similar to the Catholic orphanage she grew up in.

While I enjoyed Warrior Nun, I found these scenes between Ava and the OCS hard to stomach, almost triggering, as the nuns basically gaslit Ava for four episodes. The writers failed to address these issues in the last four episodes of the season.

Kori discussed this oversight in her first Warrior Nun piece, but the problem gets worse when you delve deeper into the story that Berry and his team are telling. Back in October, I wrote about ‘non-survivor privilege’ — which refers to how those without a worldview shaped by abuse dismiss and blame victims — and how it plays into the way that the media depicts trauma survivors. The writers’ oversight, and some of the fandom’s subsequent treatment of Ava, reflects ‘non-survivor privilege’.

And to be clear, I am not advocating for writers to publicize their personal histories and potentially open unnecessary wounds in order to be ‘valid’ enough to write stories about trauma. A person’s history of trauma or lack of one should not dictate if they should be allowed to engage with these kinds of storylines. When I refer to ‘non-survivor privilege’ in regards to media, I am not referring to any single individual’s privilege but rather to social norms that affect what stories we prioritize and how we frame them. An oppressive world relies on and encourages people to not see abuse for what it is, and thus oppressive systems go unchallenged.

For lucidity, I am breaking this topic into three articles. Today’s piece focuses on Ava’s traumatic background so as to lay out the context of her story, as the show makes clear through cinematic language that she survived abuse. As I will lay out in later pieces, Warrior Nun contradicts itself by creating such a backstory and then not addressing it properly in the second half of the season.

Overall, Warrior Nun presents Ava as an abuse survivor who grew into an empathetic, subversive feminist, but viewers can easily miss that as the show does not address the Sisters’ mistreatment of Ava. Their disregard for her emotional well-being in the first half of the season drowns everything else out. Since they are never called out on their behavior, Warrior Nun runs the risk of downplaying its protagonist’s backstory and ignoring her characterization because it relays conflicting messages. In a world that prioritizes non-survivor privilege and the subsequent denial, Warrior Nun does not seem to fully realize that it is telling a narrative about surviving abuse.

Warrior Nun Gives Ava Some Dark Roots:

Ava Silva’s (known) backstory centers around her first trauma because that set her on the path that led to the young woman we meet in the first episode. While on holiday in Spain, a seven-year-old Ava and her mother are involved in a car accident, and Ava is the only survivor, her injuries leaving her paralyzed from the neck down. She winds up in a Catholic orphanage, as she had no family and because her mother belonged to the Church. For the next twelve years Ava is trapped both in Spain and in a bed.

This original trauma and subsequent imprisonment shape her psychological development and explain her specific reaction to the Sisters, how she runs from her problems in multiple ways. For Ava, she wakes up one day after the accident, almost completely paralyzed, and her mother is dead. Professor Kristina Scharp describes a type of grief for those who estranged from their families, but I think some of that experience resonates with Ava’s alienation from society:

“It’s something we call ambiguous loss, where even though the person isn’t physically gone, they’re psychologically gone. And it’s extremely difficult, because it accompanies something called disenfranchised grief, which is where this grief isn’t acknowledged by people, so oftentimes, these people aren’t getting any support because it’s very hard to talk about.”

Her mother dies without Ava in attendance, and she may not have been able to go to the funeral or even her mother’s grave. I suspect the latter, as her caregivers were not the sort who went out of their way to enrich her life, leaving her to lie in bed all day, confined inside. In the first episode, Sister Francis reinforces this possibility when she mentions that Ava never left the orphanage. And from what we know of Sister Francis, I doubt she would have been the ‘sentimental’ type to take an orphan to her mother’s grave unless she could have weaponized the child’s grief.

This disenfranchised grief may also resonate with viewers, especially those who lost family to COVID, and for Americans, as we were abandoned by our government. And speaking of corrupt institutions, Sister Francis psychologically abused Ava, culminating in her poisoning Ava to death. Francis is a fairly classic murderous Angel of Death. Ava endured abuse under the guise of religion, living at the intersections of gender and disability, and that factors into her understanding of belief, practitioners, and the institutions that empower the few.

Overall, Ava’s storyline recalls ‘Religious Trauma Syndrome’ (RTS). Dr. Marlene Winell coined the term in 2011, defining RTS as “the condition experienced by people who are struggling with leaving an authoritarian, dogmatic religion and coping with the damage of indoctrination.” She compares the symptoms to P.T.S.D., but in my opinion, Ava’s version of RTS would map more cleanly onto C-P.T.S.D., which refers to complex trauma engendered by long-term, often interpersonal trauma, and it usually comes up in cases of child abuse. This is not to diagnose Ava but rather applying a specific lens of analysis to her character.

For twelve years, she suffered abuse in which her primary caregiver castigated her as a devilish sinner and as a burden, and on top of that, she had little social interaction outside church officials, forcing her to grow up without consistent support. As far as we know, Ava’s only friend at the orphanage was her roommate Diego, a young, terminally ill boy Sister Francis tried to kill in 1×04, ‘Ecclesiasticus 26:9-10’. It’s not unreasonable to think that Ava had other friends at the orphanage over the years who died suddenly and/or mysteriously, with the implication that Francis had murdered them too. There’s also no indication that Ava even has real religious faith and thus was forced to live within a patriarchal institution whose views she had to fight against everyday. Sister Francis embodied this struggle.

Over time, viewers learn that Sister Francis regularly called Ava a ‘burden’ for her disability and never engaged with her emotionally, only conversing with Ava formally, devoid of any warmth or compassion. In a flashback from 1×03, she even dismisses Ava teaching herself how to move her fingers. It reflects how Sister Francis has dehumanized Ava in her mind to only a ‘poor, crippled girl’.

Later, an OCS priest named Father Vincent investigates the orphanage in order to find out more about Ava. Sister Francis refers to Ava as a ‘difficult girl’ and as ‘ungrateful’. Abusers often weaponize gratitude as they point-score their targets and guilt-trip them. Sister Francis clearly did this, verbally abusing Ava for more than a decade and trying to shame her for her limited mobility and refusing to acknowledge Ava’s personhood. By branding Ava as difficult, Sister Francis could dismiss Ava’s wants and needs as unnecessary, as too much.

Abuse f*cks with a target’s mind and body, and numerous writings on trauma acknowledge the culture shock that affects survivors. For targets to become survivors, they must upend their lives and sometimes even move out of their homes, their social connections reshuffled as some loved ones side with the perpetrator and/or distance themselves from the target. Winell describes RTS as rooted in a similar existential destruction, noting,

“[R]eligious indoctrination can be hugely damaging, and making the break from an authoritarian kind of religion can definitely be traumatic. It involves a complete upheaval of a person’s construction of reality, including the self, other people, life, the future, everything. People unfamiliar with it, including therapists, have trouble appreciating the sheer terror it can create and the recovery needed.”

Thus, Warrior Nun beginning with Ava literally resurrecting fits well into an abuse storyline, as the fantasy element echoes the psychological reality for survivors. Long-term trauma and escaping abuse embody a kind of death — which targets and therapists alike refer to as ‘soul murder’ — and Ava being a former quadraplegic also fits well into the metaphor of healing, the target regaining mobility after having been paralyzed into submission and isolation by their abuser.

Throughout its first episode, ‘Psalms 46:5’, Warrior Nun relays the oppressive nature that the Catholic Church has been for Ava and her acknowledgement of that oppression. The fact that the writers then do not examine the Sisters’ mistreatment of Ava (as I will examine in parts two and three) makes all the work they put into her backstory and character introduction all the more frustrating.

None of this is to say that Ava isn’t a Glorious Dumbass and the human equivalent of a golden retriever. She’s quite resilient (as I will discuss in part two), and discussing her backstory isn’t to dishonor that resilience but rather an exercise to better appreciate her character. Acknowledging Ava as a survivor is to accept her as a complex character and a young woman on the cusp on a self-started coming-of-age.

Ava Relives Childhood Trauma & Then Some When She Resurrects:

When the first episode starts, the audience hears Ava in voiceover while her corpse stares unseeing at the camera. The camera then introduces Sister Francis as a bitter, judgemental nun who declares Ava is hellbound. Sister Francis degrading a dead girl villainizes her from the get-go, and she reinforces that when she suspiciously instructs the priest to not list Ava’s cause of death. She is the archetypal cold, cruel nun who haunts recovering Catholics years after they have left the Church and left school. And her appearance at the morgue creates a dark contrast to Ava’s original trauma of her mother’s death and paralysis for viewers later in the season.

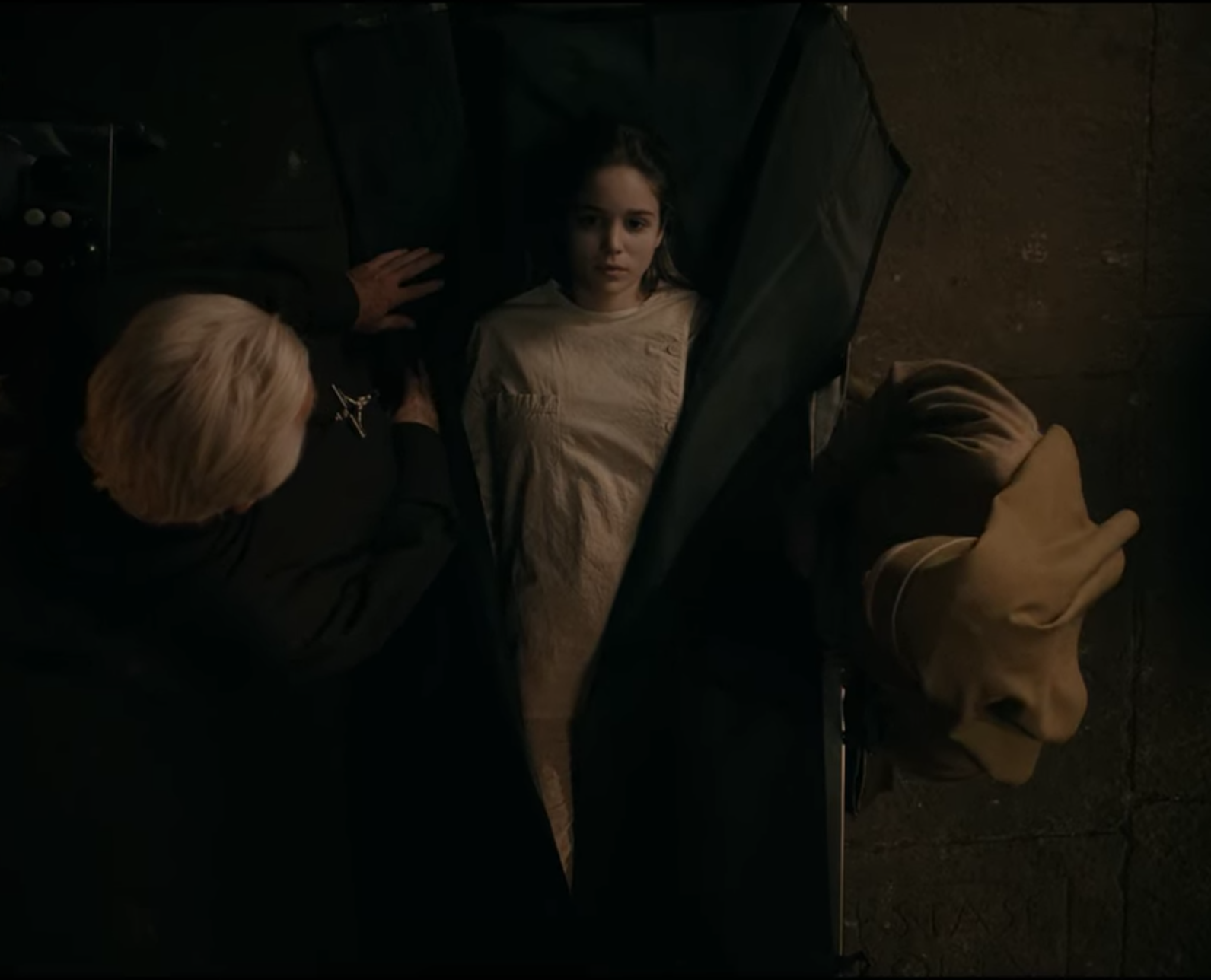

At the beginning of Warrior Nun, Sister Francis as Ava’s second mother figure sends her body off. Additionally, 1×04 includes three flashbacks that track Ava’s relationship with Sister Francis, and the first one shows their meeting. Twelve years earlier Ava had woken up in a bed, calling out for her mother and complaining about her numb legs. Similarly in the first episode , after the halo is placed in Ava’s back for safekeeping, it resurrects her, and the first thing she does is scream, reminiscent of a newborn crying. The set-up is reminiscent of her first day at St. Michael’s as she wakes up alone and her life completely altered, except this time she can walk.

And it should be noted that Ava’s rebirth comes with a lot of unaddressed trauma besides the whole being murdered thing. In the morgue, she immediately witnesses a man murdering a woman (actually a nun). A demon then possesses the man, and without understanding what she’s seeing, Ava destroys the possessed man by striking him, having unintentionally activated the halo in her back.

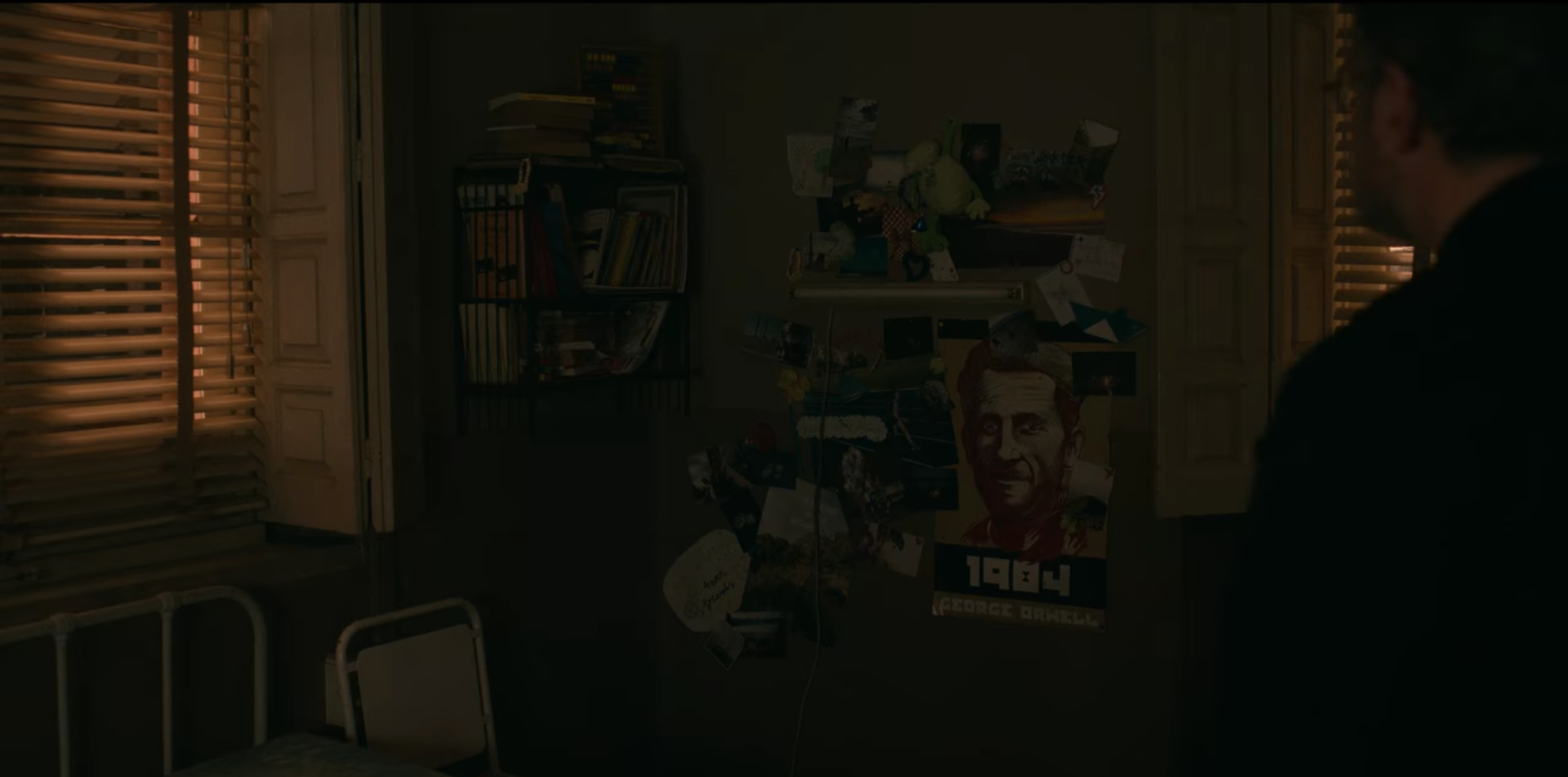

Throughout the rest of ‘Psalms 46:5’ Ava explores her newfound freedom, and Warrior Nun acknowledges that she is escaping a type of church-sanctioned captivity. The first religious symbol we see associated with her/hanging over her — that isn’t a religious person’s cross — is a giant dark and/or black cross that lurks behind her like a shadow as she escapes the morgue. It communicates that Christian iconography and thus the Church itself watches over her like a controlling parental figure, and it recalls the 1984 poster in her room, the looming authority figure.

Furthermore, the moment she begins to embrace being alive and/or possibly being Hell, she runs through a darkened alleyway with a bright light at the end. This new-beginnings tunnel imagery incorporates prison imagery because of grated windows and doors on the buildings that frame the setting.

She understands this power dynamic too.

Ava briefly returns to St. Michael’s Orphanage and seeks out Diego because of his familiarity with comic books and science fiction storylines. She says to him, “The Catholics are a little twitchy about who gets to be resurrected. Unless they control the narrative.” While the fandom often jokes about Ava’s lack of awareness about social mores and being a dumbass, she’s actually quite astute, her intelligence rooted in intuition she had to suppress. But I will discuss that point later.

As I mentioned, Ava has a 1984 poster in her room, and this says something about her character because the poster makes up the largest part of the collage by her bed. Viewers can’t miss it. In terms of the orphanage, the uniforms evoke prison imagery with their drab, blockish design. Overall, Ava knows that resurrections aren’t the only narrative the Church has sought to control, as Sister Francis and St. Michael’s tried to define her as a ‘cripple’, in addition to them shaming her for any ‘sinful’ thoughts she would have had. Such a level of control is reminiscent of the policing of thoughtcrimes described by George Orwell in his infamous novel.

After Ava bids Diego goodbye, Warrior Nun continues to reinforce the Church’s effect on her. Ava wanders onto a lush beachfront estate later in 1×01, almost drowning in the pool, when a charming young man named J.C. rescues her. He convinces his merry band of friends to let her stay with them, and they take her to a nightclub named ‘The Prison’. This provocative name is in reference to the building’s past. Then in the second episode, Ava sneaks into a party with her new friends of sorts and soon enough spots a priest. This clergyman, Cardinal Duretti, is attending for political reasons. Viewers watch Ava cling to her crush and hear her freak out in voiceover, wondering, “Is he [Duretti] here to take me back to St. Michael’s?” Even though Ava is a legal adult, she panics at the thought of getting into trouble and the possibility that she could be dragged back to her childhood home.

Targets and survivors struggle through the trauma recovery process for many reasons, and that includes feeling safe and independent from their abusers. After living under someone else’s tyranny for so long, they have to internalize the fact that their abusers will not be able to confine them again. And so the Sisters kidnapping Ava in this episode and essentially imprisoning her at their church in 1×03 taps into one of Ava’s deepest fears while she navigates this vulnerable state.

Remember, Ava is alone, penniless, and homeless when not squatting with JC, and she has little real-world experience to guide her as an able-bodied woman under capitalism. She is fueled by joy, jokes, and the possibility of a normal, fulfilling life. So when the OCS takes her and forces her to live as a nun, they essentially drag her into her personal Hell. In terms of RTS, Ava suffers retraumatization because the OCS wants to use her as a weapon of God, reinforcing Sister Francis’s message that Ava only has worth if she can be ‘useful’.

Warrior Nun does one Hell of a job (pun not intended) in creating a compelling, intensely dark backstory for its protagonist. Creating the kind of pain that would motivate the focused compassion we see Ava grow into later in the season. But all of this foundation reads a little hollow over the subsequent episodes because the narrative does not acknowledge Ava’s trauma and how the Sisters recreated it for her, how the Sisters acted more like Sister Francis than sisters-in-arms. One of the major ways that ‘non-survivor privilege’ colors the stories we create is in the fact that so often we traumatize characters but never have them talk about it, and I mean really talk about it.

~

Check out part two for more analysis on Ava’s relationship to the OCS and to the Sisters and for obscure trauma facts!

Images courtesy of Netflix

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!