Among the many different sub-genres of American noir, my favorite is those that show how big business is akin to organized crime and, in many ways, more brutal and violent. What can I say? I’m nothing if not consistent.

With the Sag-Aftra and WGA strike, this niche seemed apropos.

Byron Haskin, a cinematographer himself from the silent era, dabbled in genres ranging from noir to science fiction. He directed such classics as 1950’s Treasure Island and 1953’s War of the Worlds. Interestingly, he was among the Warner Brothers’ special effects department that developed the rear-projection system.

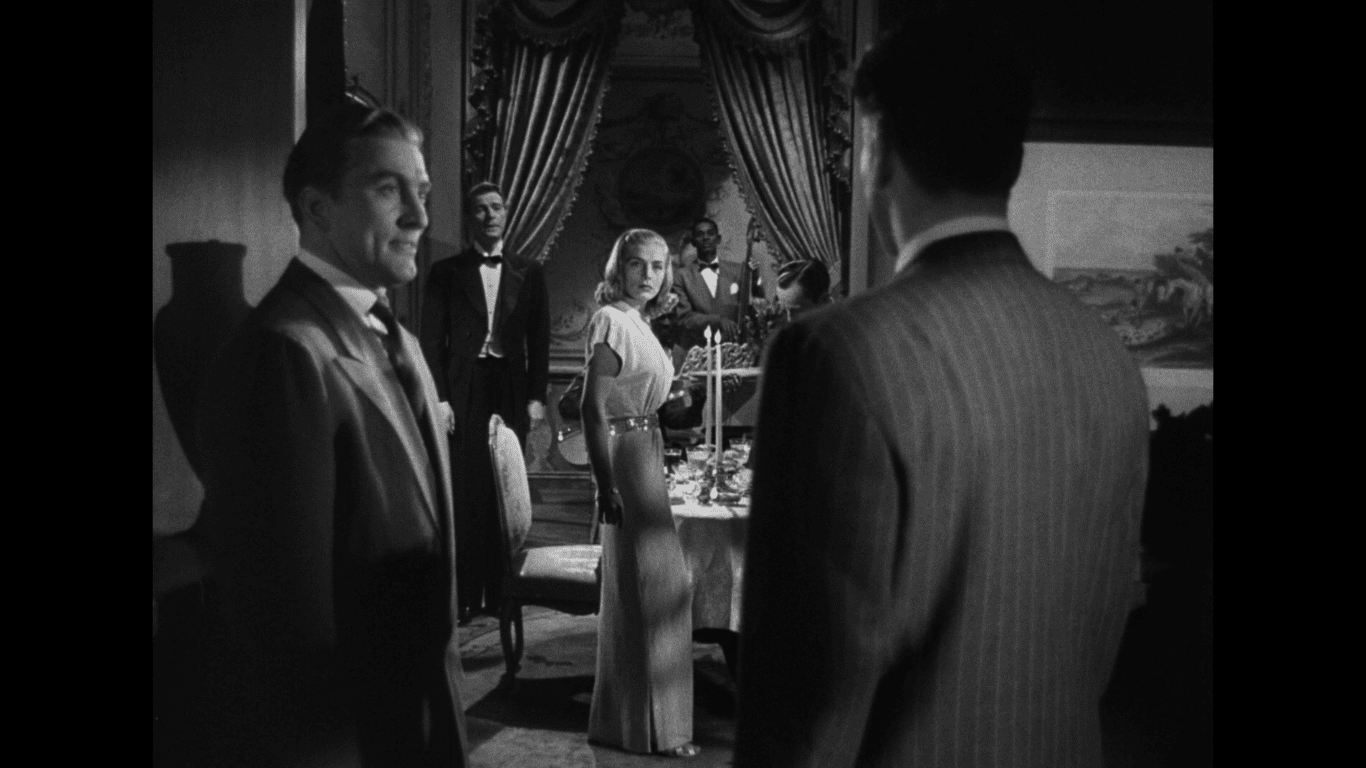

All that being said, I Walk Alone is not his best work, nor is it often ranked on lists of best noirs or much talked about. Still, I can’t help but find myself drawn to this shaggy dog film every few years. Perhaps it’s because the femme fatale Kay is played by the hypnotic Lisbeth Scott, one of my favorite noir dames. Or maybe it is because of the unpredictable energy between the two leads. Burt Lancaster’s Frankie was recently released from jail after fourteen years, Frankie and his old bootlegging pal and swanky night club owner Noll, played by the king of toothy smiles, Kirk Douglas.

The script by Charles Schnee, Robert Smith, and John Bright crackles with enough wit that the stars can elevate the material. Adapted from the stage play “Beggars Are Coming to Town” by Theodore Reeves, it effectively contrasts and parallels how honest bootleggers and oily businessmen walk in the same world, but it’s how they operate and treat others that separates them.

Douglas’s Noll assuring everyone of their cut while wheeling and dealing worried about perception as opposed to Lancaster’s Frankie’s openness and brutal honesty being the key dynamic. Frankie is hardly a Saint; after all, he just got out of a fourteen-year stint, but compared to Noll, he seems like a good guy simply because with Frankie, what you see is what you get. With Noll, there’s a sort of Trumpian sense of moral larceny involved.

Back in their bootlegging days, they made a pact. If one of them got caught, they’d take the fall for the other. When they got out, they’d get fifty-fifty of their co-owned club, The Four Kings. Frankie is out and wants his cut; only The Four Kings doesn’t exist, but Noll’s newest club, The Regent, is in all the society magazines, and Frankie figures something is waiting for him.

There is. But it’s not what Frankie is expecting or what he’s owed.

For Noll, deals are only as good as the words used to frame them. But for Frankie, it’s the spirit of the agreement, what’s owed, a sense of fair play, that is the cornerstone. Noll is modern, all gloss and shine, with no substance, while Frankie is pase, stuck in the past but also a symbol of the disenfranchised, those passed over by the new era of conglomerates, the working class.

Frankie refuses to change, calling Noll but his old nickname, “Dink,” chaffing Noll’s superior attitude. At least he refuses to change until Kaye begins to help him see it’s a different world. Scott is a stone-cold dynamo who never seemed to be adequately utilized, an all too familiar tale in Hollywood, but she fits perfectly as a foil to both Frankie and Noll. To Frankie, she is a breath of fresh air and a kindred spirit; to Noll, she’s a tool, and to herself, she is conflicted because she loves Noll but feels respected and desired as a person by Frankie.

Scott is the moral center but also goes through a moral awakening. Realizing Noll’s coldness and calculated cruelty, she turns to Frankie until realizing that he is just as brutal in his way. The straw is when she learns Frankie intends on gathering a bunch of guns and barging into Noll’s nightclub and demanding his piece of the action. Refreshingly part of Kaye’s warning to Frankie is based on his gun use, “Once you use that gun, you’ll have a gun in your hand the rest of your life.”

Frankie’s plan to take Noll at gunpoint leads to one of the best scenes in the movie. Frankie and his gang bust into The Regent and hold Noll at gunpoint. Noll cooly calls in their mutual friend from the old days, Dave (Wendell Corey), Noll’s accountant, to explain to Frankie why he can’t. What follows would be hilarious if it weren’t so horrifyingly familiar. Noll claims poverty, that he is merely a pawn at the behest of the board of directors and shareholders.

Frankie’s gang look on, understanding. Unlike him, they’ve been on the outside; they’ve grown accustomed to barging into the boss’s ornate office and being told there’s no money. They apologize to Noll and leave Frankie confused and frustrated. Of course, we learn from Dave that there are “A books” and the B “books” tell a much different story. One that is obvious by the house Noll lives in, the fancy car he drives, and his lifestyle.

At one point, Noll even frames Frnkie and calls the police. Haskin and his DP Leo Tover frame Noll’s informing scene as if it’s an old hat. Relationships are purely transactional to him, and cops are merely tools. People like Dave and others aren’t people; they are pawns to be moved about.

Haskin, at times, struggles to find a visual momentum that often leaves the movie succumbing to a narrative undertow. The dialogue is sharp and crisp, but Haskin rarely lets Tover’s camera out of the batter’s box despite being a former cinematographer. I Walk Alone isn’t an ugly film, but it is sometimes oddly visually stilted. It doesn’t help that the script begins to run out of steam towards the end, with Haskin and his writers seemingly at their wit’s end with how to wrap it all up.

Still, the resolution is a rarity in allowing Frankie to reform, despite the Hays Code typically demanding he pay for his moral crimes. Something that had Bosley Crowther of the New York Times film critic of the time furious that the filmmakers were allowed to flaunt the Hays Code in such a manner. In a way, Crowther’s attitude underlines how I Walk Alone shows how rudderless our society leaves people just released from prison.

I Walk Alone gets lost in its melodrama at times, but the polarizing chemistry of Lancaster and Douglas, and Scott’s almost hypnotic gaze, keep the film afloat for the most part. But what sticks in my mind the most is how it portrays the working class fighting for what’s theirs, and that scene in Noll’s office forever burned into my mind as Dave reads off all the different holdings and companies is still infuriatingly relevant.

Images courtesy of Paramount Pictures

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!