Psycho II is so good it’s almost hard to believe it’s a sequel to a Hitchcock movie twenty-three years too late. Yet, journeyman director Richard Franklin wisely builds on what the master of suspense gave us in 1960 and creates a unique and captivating horror movie with a sly sense of humor. But more than anything, it understands the sense of play utilized by Hitchcock in a way that modern movies so often forget.

Hitchcock’s original Psycho is often called the proto-slasher and birthed a much-maligned genre. But by 1983, the slasher genre had grown into something almost recognizable to Hitchcock’s Psycho, yet had still not matured fully into what we know of it today. Tobe Hooper’s 1974 The Texas Chainsaw Massacre had come out almost a decade before Psycho II. John Carpenter’s Halloween had come out a mere five years earlier, and Sean S. Cunningham’s Friday the 13th a scant three years earlier. Over the horizon, Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street would come out the following year.

Still, in a relatively short time, the slasher genre had mutated into cheap gore fests with puritanical undertones, which makes Franklin’s undertaking all the more daunting. How does one make a sequel to a slasher that doesn’t look anything like modern slashers? How do you take a sequel to one of the most discussed and analyzed movies of all time and make it stand on its own?

Richard Franklin and screenwriter Tom Holland’s answer: give sympathy to the Devil. Tom Holland’s script boldly flips the story and has to empathize and, at times, downright sympathize with Norman Bates. One of the things that is remarkable about Psycho II is how squarely Franklin and Holland are in Norman’s camp in terms of his recovery.

Of course, the reason any of this works is because Anthony Perkins reprises his role as Norman Bates. Perkins plays Norman with the same nervy twitchiness, charm, and loneliness. But Perkins takes his iconic character and finds his humanity, giving him a yearning and sense of loss as he enters after gaining his freedom.

Psycho II is the rare 80s film that shows social programs working. Norman’s doctor, Dr. Bill Raymond, played by Robert Loggia, even laments about cuts to social programs because it means there won’t be a social worker looking in on Norman to see how he is. They even have to return Norman to the infamous Bates Motel and the iconic house on a hill because there are no halfway houses for him to stay in.

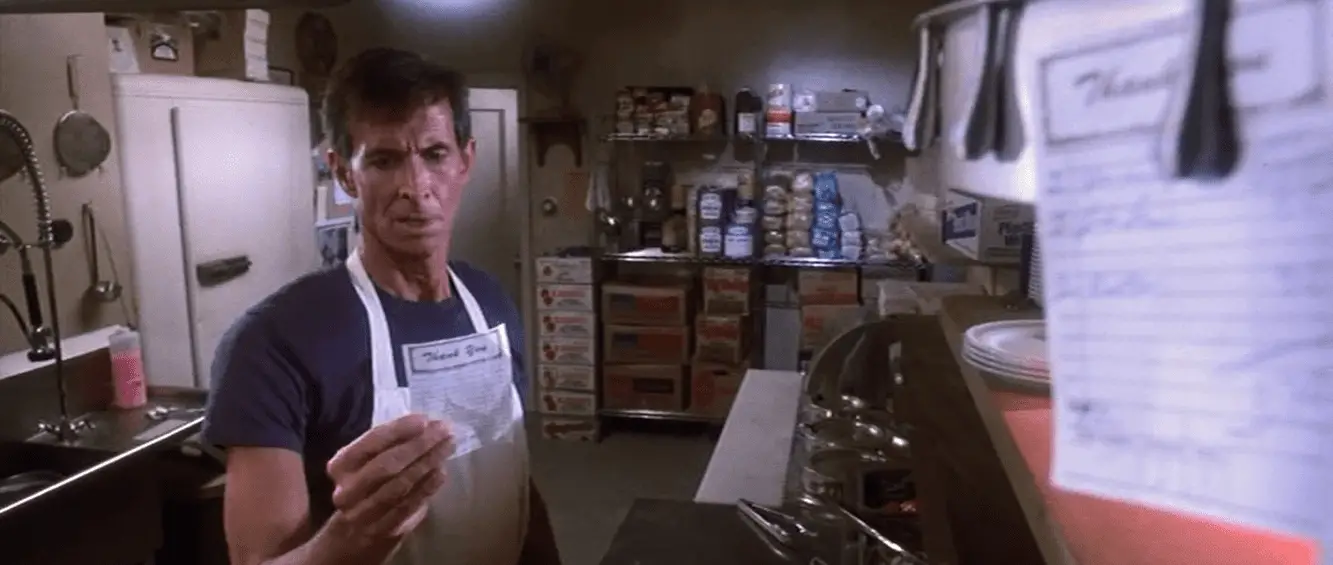

Franklin and Holland flip the script by making society the monster as Norman tries to reenter society after paying for his crimes. He gets a job at the diner and meets Mary (Meg Tilly), who soon finds herself needing a place to stay, and wouldn’t you know it Norman has a few rooms. However, the man who runs the motel, the skeevy Warren Toomey (Dennis Franz), might have a few things to say about his new boss bringing a lady to the Motel.

Psycho II shrewdly doesn’t ignore the original. Instead, they open Psycho II with the now iconic shower scene before cutting to the courthouse, where we see an older Lila Loomis (Vera Miles) furious at Norman’s release. Holland’s script is filled with little references to the original. My favorite is when Tilly’s Mary bumps into Norman in his house and screams, terrified. Norman laughs. “I don’t kill anybody anymore, remeber?”

Shot by Dean Cudney and edited by Andrew London, Psycho II looks better than most slashers of the time. Heck, it looks better than most movies now. One scene in the diner is edited and shot that manages to channel Hitchcock without trying to copy him. Indeed, much of Psycho II feels not like an homage but a continuation, building on what came before.

Franklin and Holland sit back and watch the bodies begin to pile up around poor Norman, but we know he’s not the killer. We’re with him; we see what he sees. We also know it can’t be Norman’s mother because she’s dead; it’s the entire premise of Psycho for crying out loud. But Norman thinks he’s slipping.

While Norman is hardly innocent, yet we can’t help but feel for the poor sap as someone tries to drive him mad again. Holland’s script not so subtly explores how vengeance rots and warps our sense of justice, which for the 80s is a rarity. It even goes so far as to show how revenge can turn your worldview upside down by having Sherriff John Hunt (Hugh Gillin) be the voice of reason. He suspects Norman but soon realizes someone is out to get him and finds it more than a little perverse.

Perverse is the bread and butter for Psycho and Psycho II, especially with how Franklin plays Norman and Mary’s relationship. At times paternal, at others they are more two lost souls who have found each other. Or maybe there’s something else; after all, Mary doesn’t tell Norman she found the peephole in the bathroom–though that may be because of something else.

Tilly and Perkins together are one of the many reasons Psycho II is so spellbinding and unreasonably fun. They gravitate towards each other as if they were fated, which makes the reveal all the more tragic. Psycho II has twists and turns, and if I’m being honest, I felt it had one twist too many, leading to an ending that, while I understood why they went there, I found myself wishing that a film as somewhat daring as this was just a little more so in the end.

Horror films, particularly slashers, are uniquely suited to being filmic in nature. That so many rarely take advantage of this aspect is due to the capitalist system that funds and produces the movies and not the genre’s fault. What makes Psycho II so thrilling and compelling is that Cudney and Franklin build on Hitchcock and his cinematographer, John L. Russell.

Cudney’s camera, along with Andrew London’s editing, breathe life into Psycho II. Together with Franklin, the trio makes the tension visceral with angles and visual language, building suspense and allowing us to get to know Norman Bates. It helps tease out magnificent layered and pulpy performances from Franz, Gillin, and Miles. To say nothing of how it makes the relationship between Tilly and Perkins vibrate unpredictably as the story unfolds.

Even Jerry Goldmsith’s score chooses to go its own way. Bernard Hermann’s score to the 1960 Psycho is known to people who’ve never seen the movie. But Goldsmith use the original score as a springboard for Goldsmith’s textured and taut score.

Psycho II may seem like a crass cash-grab sequel, but it never feels cheap or as if anyone is phoning it in. Franklin crafts Psycho II with as much love and care as the original, never falling into embarrassment in trying to distance itself from the original or the genre. Perkins was a treasure of the screen, and if nothing else, Psycho II is a reminder of how rarely he was used to his fullest talent.

Images courtesy of Universal Pictures

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!