When the mood strikes I will, occasionally, browse Kickstarter for new tabletop games. There are lots of different types, from board games to remakes of old games. And the play styles of the games range from purely story based to incredibly mechanics focused. The game I found isn’t really any of those, but seemingly a combination of them all. This new game, Wicked Ones, is a fantasy game about being a monster, and building a dungeon.

Dungeoneering For Fun & Profit

The Wicked Ones ruleset uses similar rules to another tabletop game, Blades in the Dark. In Blades the player’s character is a criminal, working with a small time gang. The goal of the game is to survive and grow their gang. It is unique in that characters both have a personal character sheet, and a shared ‘gang’ sheet which tracks the stats of the group the player is a part of. Wicked Ones does something similar, giving players both a personal ‘monster’ character sheet and a group ‘dungeon’ sheet.

Yes, monsters. In Wicked Ones the players are controlling the monsters. And the short PDF about the mechanics of the game makes this point very clear. These characters are not anti-heroes. They can perform heroic deeds, but only in pursuit of a greater evil; driving off an invasion of kobolds so they don’t interrupt the summoning of some dark god, for example.

Creating the character isn’t a matter of picking a race and class like in other fantasy games. In Wicked Ones, the player isn’t picking a class as much as an archetype. Each archetype has different stats and skills, but most of the archetype’s physical descriptions are left blank. The archetypes can range from a Brute (Powerful and intimidating brawlers) to a Shadow (Sneaky and elusive rogues). These archetypes give players more freedom than selecting a race and class. The Brute can be an orcish barbarian, or a goblin pit fighter. This gives players a great deal of flexibility when it comes how they portray the monsters.

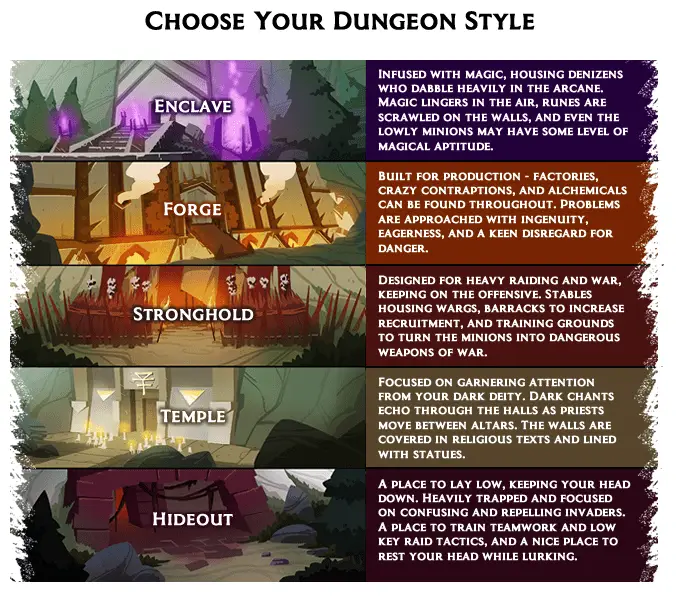

The dungeon sheet that the players share is similar to their individual sheets in that there are different archetypes. Enclaves, Forges, Strongholds, Hideouts and Temples are all the different dungeon archetypes players can select. Unlike the monster sheets though, players are expected to cooperate and draw the actual map of the dungeon, adding more rooms as they expand it. Should the lava pit trap go in before the dragon lair, or after? And what about treasure rooms? And don’t forget beds and bathrooms and dining halls for the imp minions. An army marches on its stomach after all. If some of the players are intimidated by the idea of having to design a dungeon, the book promises to include some tutorials on dungeon design.

Play Order

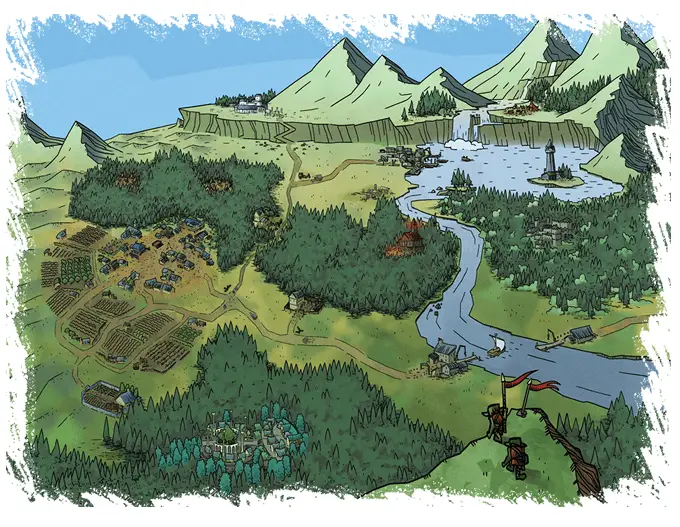

Once the players have a basic idea of what they want their dungeon and characters to do, the game proper can begin. Play consists of four distinct stages. The first, the Roaming stage, has the characters searching for information and scouting different factions and targets for the next stage of the game. The second stage is the Raid. The characters pick a target, plan what to do, and jump into action. Raiding a caravan, destroying a farm, or sneak into a city to poison the well. All of these options and more can be done in the Raid stage. The third stage is the Lurking stage. This is when characters can rest and recover from the raid stage, as well as start building more rooms and defenses for the dungeon. And they’ll need it for the final stage: Defending. In this stage heroic adventurers attack the dungeon, looking to kill the monsters and loot the treasure. With the help of the traps and the map of the dungeon, players will attempt to drive off the invaders.

According to the Kickstarter, most games will last sixteen sessions, with a Defending stage happening once every four sessions. This time limit is rather intriguing to me, as it means that the game can’t drag on forever like some campaigns have a habit of doing.

Inspiration From the Past, Ideas For the Future

Some people reading this may be thinking that this game sounds an awful lot like the old PC game Dungeon Keeper. That’s intentional. Dungeon Keeper was a massive inspiration for this game. In fact, the designers of War for the Overworld, a spiritual successor to Dungeon Keeper are allowing some of the stretch goals to be based on the newer game. And they might reach those stretch goals as well. At the time of this writing, there are eight days left in the crowd funding campaign, and they’ve already reached four of their stretch goals. And if you want to see more about the game, or see examples of the game in action, you can visit the Kickstarter here. I personally will chip in some. After all, there’s always room in the world for more monsters.