True crime documentaries and podcasts are a bane of the modern era. They are the epitome of a system that uses trauma and misery as grits for the mill of capitalism. Worse is how they employ armchair observation, which requires neither expertise nor curiosity.

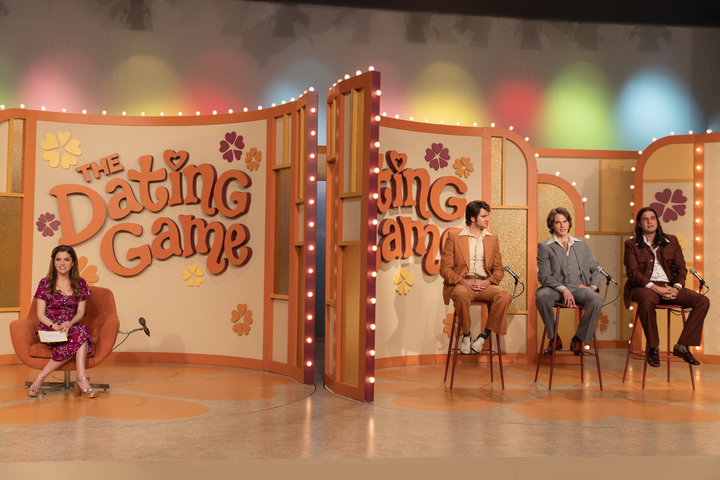

Anna Kendrick’s directorial debut, Woman of the Hour, about the serial rapist and murderer Rodney Alcala who ended up a contestant on The Dating Show in the 1970s, tries to sidestep these issues and, to some degree, succeeds. But when it doesn’t, it makes the well-meaning, albeit ham-fisted dissertation of how misogyny is the background radiation of women’s day-to-day lives feel as if it is merely reheated leftovers of better movies on the same topic.

Ian McDonald’s script attempts to turn a historical curiosity into a full-blown narrative exploration. It’s the equivalent of taking a finger sandwich and trying to make a whole meal out of it. The fact is that Rodney Alcala, played chillingly by Daniel Zovatto, was a guest on the dating show, and he won, is true, but also has nothing to do with the assaults and murders. It’s an eerie antidote to an otherwise horrifying spree of inhumane psychopathy.

Kendrick and McDonald are less interested in how Rodney got on The Dating Show and more in trying to show the overall dehumanizing culture that allowed Rodney to flourish in the first place. Woman of the Hour skips through time in a ho-hum fashion as Kendrick attempts to show us the trail of bodies Robert has left in his wake. But the time skipping does little to add suspense or do more than showcase Kendrick’s ability to showcase horrible events tastefully yet effectively.

At the center of Woman of the Hour is Kendrick as Sheryl, the real-life contestant who chose Alcala but who, after meeting him, declined to accept the show’s prize, a trip to Carmel, California, because of how creepy she found him. She tries to show the way Sheryl navigates sexism and systemic misogyny, but in the end, she’s taken a woman who is a minor footnote of the case and made her the co-star next to the actual serial rapist and murderer.

Yet, despite this, Kendrick finds little moments of truth. Her true talent lies in her ability to elicit lived-in performances from small characters, even if McDonald’s script is determined to turn them into walking symbols of cliche messaging. While McDonald tries to paint two-dimensional characters, Kendrick finds ways to make them seem alive and fleshed out.

Pete Holmes plays her next-door neighbor and friend, Terry, with whom Sheryl sleeps because it would be easier than telling him no. It’s a great scene not just because it’s one of the few subtle scenes in the movie but also because shows the little grey areas women have to navigate with men to keep from being attacked. Nothing in Terry says he would hurt Sheryl, but Kendrick shows the little ways Terry refuses to listen to her, such as when he comes into her apartment and refuses to leave as she takes a phone call.

Zovatto, as Rodney Alcala, is appropriately dull and menacing while also showing how such a man could convince women to be alone with him. Kendrick eschews popular portrayals of serial killers and goes out of her way not to make Rodney charismatic. He’s a blank slate, an empty vessel that he fills up with whatever personality needs to trick the women into being alone with him. Zovatto nails this pathetic emptiness, his eyes showing nothing inside.

But the real coup de grace is Autumn Best as Amy, the final victim of the film. She plays a young girl who recognizes after her assault the best way to survive is to play to Rodney’s deranged ego. She apologizes to HIM and asks him to keep it a secret, essentially taking responsibility for her assault, which gives her time to make her escape.

Best is phenomenal, and Kendrick and her cameraman, Zach Kuperstein, do a gut-wrenching job capturing the moment. She captures Best’s face and sees the wheels spinning as she begins to talk herself out of danger. It’s one of the best scenes in the film simply because of how unafraid Kendrick is of going to such an emotionally dark place.

Kuperstein capably photographs Woman of the Hour but rarely rises above anything polished and slick. However, in the last thirty minutes of the film, Kendrick puts her foot to the metal, and a film that has been limping for much of its runtime begins to fall into a confident jog.

There’s a moment in the studio parking lot where Sheryl realizes that all is not well with Rodney, showcasing Kendrick’s talents as an actor and a director. The way she utilizes space and editing in this scene creates a sense of threat and danger without flourishes. It’s a shame the rest of the film isn’t crafted with the same confidence.

Kendrick has publicly stated she refused payment for Woman of the Hour, saying she donated her director’s salary to abuse survivors’ charities. She did so because it didn’t feel right to profit from exploiting the trauma of women.

Kendrick strives to ensure Woman of the Hour never feels exploitative. Yet the way Sheryl’s story is made front and center in McDonald’s script while making Rodney, the de facto main character, muddies the waters. They attempt to tell a broad story about women’s existence in modern society but root the story’s center in a specific incident. However, as the film goes on, it begins to feel, intentionally or not, exploitative.

Woman of the Hour is a better-looking movie than Netflix usually delivers. Plus, Kendrick and McDonald use humor to showcase the darker side of Hollywood, such as a scene where the casting directors talk about Sheryl as if she isn’t there.

Woman of the Hour is a movie I spent much of the time admiring but not really liking. When I liked it, I really liked it. However, too much of the film felt like trying to justify its existence, attempting to show how men fail women. Its main goal, I suspect, is to show how often we turn real people into characters for the sake of content. Yet, by doing so, Kendrick falls into any of the same traps.

Storylines like Laura (Nicolette Robinson), the best friend of one of Rodney’s victims, who was in the audience that day and recognized Rodney. Her mad dash to find the producers, her confrontation with her reticent boyfriend, and the way the sick joke the security guard pulls on her feel weightless. Kendrick and McDonald intercut Laura’s scenes with Sheryl’s on the game show. They attempt to make the back-and-forth act like a ticking clock, as evidenced by Dan Romer and Mike Tuccillo’s bombastic score.

The ending of the sequence is anti-climatic, but not in the way I think Kendrick meant it to be. It feels like padding, as opposed to the likely allusion of how often the system fails women, even when they try to avail themselves of it. But, instead of being illuminating, it merely comes off as tedious.

One wonders if it would have been better to invent a story similar to the incident and go from there. If only because so much of what we see of Sheryl on The Dating Show was made up. Sheryl didn’t invent questions on the fly, and Rodney came across as goofy and sexist like the other bachelors. Here again, is the sin of modern true crime, the finger-wagging, “How could you not see,” which, while understandable, overlooks the true horror of sometimes you can’t.

The epilogue text crawl at the end of Woman of the Hour is perhaps among the most chilling. It puts Kendrick’s aim into stark focus: the system doesn’t care or work. This seething sentiment runs underneath much of the film but never quite makes its heat felt towards the end.

Images courtesy of Netflix

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!