Content warning: discussion of suicide

Delta Rae in Review:

Back in November, I analyzed Delta Rae’s music video (mv) for their breakout single ‘Bottom of the River’ (BotR). The piece covered the historic and literary connections that the video shares with the witch archetype, building on material I generated for my first article on ‘feral feminism’. Feral feminism is a politically-charged aesthetic that I am working to articulate. This article will be examining one of their last singles while under the umbrella that is Big Machine Label Group (BMLG). Their song, ‘Do You Ever Dream?’ (DYED), catalyzed a creative reclamation, the band having been in a stupor before writing the song. They released the song and video on September 5th, 2018, announcing the project with an email that detailed its creation. “We don’t know if we’d still be a band if we hadn’t made this video,” they said, explaining how touring and professional roadblocks were wearing them mentally. They also hinted towards a lack of professional support, a subtext that is now glaring in light of recent events. Taylor Swift left BMLG back in November 2018, Delta Rae left this past summer. Just as Delta Rae was leaving, Swift called out BMLG and its associates for poor business practices, and she has used the flare-ups to draw awareness to insidious parts of the industry. (For more information and sources on this subject, check out my other articles on the music industry.)

The Hölljes siblings (Brittany, Eric, and Ian) wrote the song as an expression of Brittany’s heartbreak and frustration over a failed relationship. Dan Huff later produced DYED?. The song spoke to them, and when their past director, Lawrence “Law” Chen, came to them about filming in Iceland, they knew what song they wanted to use. Chen directed their BotR video as well as their video for ‘Scared’. The creation of this music video (mv) truly was a labor of love. In a Behind-the-Scenes (BTS) video, Eric details the video-making process, pointing out their lack of funds and subsequent creativity in filming techniques.

My analysis will not follow the music video linearly, instead reviewing certain scenes in specific terms, bouncing back and forth, layering themes and ideas to best understand the video. For simplicity’s sake, I will also be referring to DYED?’s character as ‘Brittany’ even though she is not playing herself. Our longtime writer and my longer-time friend, Angela, is a lover of all things Icelandic, and she provided some interesting insights on its geography and culture. Her thoughts are noted here too.

The video follows a woman as she journeys through Iceland, chasing after her distant lover. It begins though in North Carolina, and as the car pulls up into a driveway, Brittany begins to sing, a little disconnected from the gathering as she hugs people. While I interpreted them as being her friends, these people could just be her lover’s family and friends, leaving her an outsider. She would just be going through the social motions. This dissociation persists over dinner, her eyes a little glazed over as she watches people converse around her. When she goes to bed that night, she turns over and sees her lover walking away, and Brittany follows after him, stepping out into the Icelandic countryside. Wrapped in a luxurious fur coat and wearing a silvery dress, she traverses the island barefoot, scaling mountainsides and navigating rocky hills, all in pursuit of him. The climax comes when he walks off a cliff, walking through the air, and she still chases after him, falling to the ocean below. In the transitional moment, Brittany falls into bed and wakes up, realizing that she had dreamt the whole experience. Fired up from her revelation about her lover’s cold toxicity, she packs her bag and leaves, stealing one of the friends’ cars in the process. The mv closes with her hand swaying out the open window, a resonating bookend.

‘Do You Ever Dream?’ explores the emotional, liminal space that a woman journeys through on her way to becoming independent and thus unconventional, adapting elements of the BatB romance structure for a coming-of-age story. It builds on the time-honored storytelling tradition that centers a young woman’s coming-of-age in a dreamlike setting.

Dissociative Themes:

‘Do You Ever Dream’ opens with a clever Easter egg. Britney hums a song from Delta Rae’s second album, After It All. Not only was the song from their last full length-record and preceded their time under BMLG, it was also titled ‘The Dream’ and described a woman dreaming repeatedly dreaming about falling. The song has a creepy edge to it, lending Chen to use it for the ‘Scared’ mv and now for this one. It was also used for gothic promo of After It All. Even if listeners don’t instantly recognize the tune, the melody alludes to something off about what we’re seeing.

The beginning of the video exemplifies the subtle interactions that reveal a relationship between people, the distinct psychological underpinnings. As she hums, Brittany lazily waves her hand out the window, enjoying the wind. The window then closes, and as Brittany moves her arm in surprise, the camera shifts to her love interest as he turns on the A.C.. The window’s mechanical sound is a sharp contrast against the gentle hum of the car. Brittany’s glance at him reveals bottled-up resentment and confusion.

Opening the car window versus using A.C., without saying anything to her, functions as a microcosm of their relational problem: incompatible desires. She wants the natural, wants to experience it as much as she can with her own body, removing a man-made impediment (the window). He shuts things down, he relies on machinery for sensation. He goes after his wants without considering her wants or needs. One small detail cascades into more with these kinds of interactions. The couple’s disconnection from nature relates to the emotional disconnection in their relationship, which bleeds into the Self. This disconnected, inhibited Self rooted in a bad relationship forms the video’s emotional core and narrative drive, its arc of character development.

The BTS video provides interesting tidbits of trivia, such as the Easter egg on Brittany’s phone (t. 00:39). Her lock screen is a picture of an Icelandic cliff, presumably the cliff that she later falls from. The character would logically see this cliff before falling asleep, influencing her sleep. Its very presence on her phone is also indicative of her desire and love for Iceland and the outdoors. In her 2017 memoir, Priestdaddy, Patricia Lockwood ponders this desire: “A woman’s body always stands on the outskirts of the town, verging on uncivilization. A thin paper gown is all that separates it from the wilderness. Half of its whole being is devoted to remembering how to live in the woods,” (p. 257). Brittany’s character fears over her and her lover’s future, his possible disinterest, intersect with her subconscious yearning to return to a time and culture unremembered yet keenly felt. Through its lyrics and imagery, the video communicates gender tensions in relation to nature as shaped by patriarchal and capitalistic structures.

As I discussed in my previous articles on feral feminism, the rise of capitalism led to more restrictive roles for medieval women, shaped by sexual assaults and witch hunts, as well as a renewed exploitation of the earth, the kind that has led to today’s climate change crisis. Silvia Federici discusses these themes in her 2004 book Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation: “[T]he continuous expulsion of farmers from their land, war and plunder on a world scale, and the degradation of women are necessary conditions for the existence of capitalism in all times,” (p. 19). In further anti-capitalistic terms, a profound alienation exists for people, separated from the value of their work and from each other. Apathy, anhedonia, and affluenza have been some of the defining characteristics of industrialized, first-world countries over the past century, sharpening with each generation. In 1970, an anarchist group summarized this alienation, writing, “The mass is an aggregate of couples who are separate, detached and anonymous. They live in cities physically close yet socially apart. Their lives are privatized and depraved. Coca-Cola and loneliness,” (p. 90-91). Marginalized people experience this alienation from the self and from their community on a greater level, forced to comply to the dominant ideal, whether that be white or straight or male, et cetera. Patriarchal values, partially shaped by capitalistic philosophies regarding the body-mind disconnect, also reinforce these problems by prioritizing logic and reason over emotion and intuition. And in regards to women, we are shamed for expressing any emotion, dismissed as a hysteric if upset and dismissed for our passions. (This shaming and stereotyping also worsen depending on a woman’s gender presentation, race, sexuality, et cetera.) Some of the lyrics lean towards this emotional policing and hierarchy, which I will discuss later.

As I mentioned earlier, Brittany goes through the beginning of the video dissociated from the world around her, including her (possible) friends. The song’s opening reinforces Brittany’s need for nature as she questions her lover’s priorities: “Do you ever dream?/Do you ever see the future when you look at me?/A little house in the mountains surrounded by the evergreens/A homemade meal and a couple kids.” This is partially why our protagonist’s sleep-dream resonates so much for her: that Icelandic farmstead is everything she wants, but it still leaves her empty. She barely looks at her ideal cabin because she can’t yet accept her situation, clinging to her relationship. Angela recognized the set as a Viking village that had been built for an unrealized film. She noted that this location “adds to the unreality of the family that [the characters] were trying to build.” In addition, the specifications of a ‘little house’ and ‘homemade meal’ reflect the want to escape mindless, void-escaping consumerism. Altogether, Brittany’s refrain of “Do you ever dream?” centers on her fears about her lover’s want for connection, because that is what we all ultimately want: to connect with a person and to make something solid, something tangible.

When Brittany first gets out of bed to follow her lover, walking through the sleeping house, she passes a mirror, her shadowed reflection watching her. The image connects back to BotR and Chen’s use of mirrors between Delta Rae’s two videos. In my analysis of BotR, I argued that the witch’s detached reflection revealed a psychological deficit, an internalized conflict not visible to viewers. This second mirror-bit is an Easter egg, referring back to Delta Rae’s beginnings, as well as a parallel. It communicates a similar problem. The witch and the DYED? character are struggling with themselves — the former connected to the supernatural, the latter to nature. Womanhood and nature are linked in psychological wellness and in psychological unrest. In an interview, feminist playwright Eve Ensler explained, “I think one of the reasons it’s been so easy, in a way, for us to violate both women and the Earth is this profound dissociation that exists in everyone.” The love interest’s disregard for the future, partially explained by his disconnection to nature, represents his disregard for Brittany. His apathy also reflects a dissociation of his own. He’s so distant that she questions his motives, wondering if he just uses her for sex and comfort.

Though only a dream and not a real near-death experience, her fall from the cliff breaks her dissociation, and it awakens Brittany physically and psychologically. From my own experiences, external factors more easily shatter dissociation, leading to a wash of intense emotions that destabilize a person for a few days. But soon enough the coldness comes back, the far-off gaze icing over the eyes. Overall, I think it’s internal forces that truly affect a person, inspiring genuine, long-term change. Rather than being pushed into awareness, the person is pulled into it by their own mind. Delta Rae captures this through Brittany’s epiphany. The video concludes with her driving the vehicle herself, taking control rather than being driven or having to follow: Her hand out the window, tracing the wind, as a fitting bookend.

Domestic vs. Domesticated:

‘Do You Ever Dream?’ does not follow the standard verse-chorus-bridge structure that dominates today’s songwriting styles. Instead, the song’s titular refrain kicks off every verse, the thematic linchpin and existential motive. The concept reminds me of Federici’s comments on magic and capitalism’s dismissal of the practice: “Prophecies are not simply the expression of a fatalistic resignation. Historically they have been a means by which the “poor” have externalized their desires, given legitimacy to their plans, and have been spurred to action,” (p. 272). For Brittany, dreams are her prophecies, the vehicle for her to verbalize her concerns and realize her next course of action. They express her will to change, to break her dissociation, as they give her goals to work towards. The refrain also connects to lyrics that speak to anxieties and tensions she feels as a woman in conflict with a man, struggling between wanting the domestic versus a history of women being domesticated.

After singing about that little house surrounded by evergreens, she questions her lover’s intentions: “Or is just the moment?/Is it the sex and the comfort and the laughs that keep you coming back?/I hate to ruin the romance baby but I have to ask.” These elements — the physical, material, and emotional — make up a relationship, but with how she lists each one, she is referring to them as individual acts, almost like body parts, dismembered from the wholeness of intimate human connection. It definitely reads as gendered due to societal expectations of the emotional labor that women bring to a relationship, how men often look for a mother-wife and not a partner.

In addition, ecofeminist Stacy Alaimo examines gender relations and activism by blurring boundaries between body and place, as noted in her 2016 book, Exposed: Environmental Politics and Pleasures in Posthuman Times. She points how the aforementioned activism can address feminist issues: “To dramatize oneself [through this blurring] is to critique the rational, disembodied Western subject’s presumption of mastery, or at least objectivity that is, supposedly, granted by detachment from the world,” (p. 5). As she traverses a frozen, wintry wasteland, Brittany sings about his self-destructive attitude, asking, “Or do you want to leave this world while you’re still young and free?/Live on the edge and leave falling in love to girls like me[?]”

The lyrics remind me of how our society dismisses young women’s experiences, writing off their values, interests, and emotions to things like hormones and sentimentality. She is confronting valorized, patriarchal rationality and stoicism, which her dreaming and dreams subvert, because to dream is to be driven by emotion, to believe in something without necessarily ‘evidence’.

These references to sex, laughter, and girls; and their interconnectivity go back to ancient Greece, at least in terms of Western culture. Though we now associate nymphs with the wild and with promiscuity, the nature spirit was also a social class for young, marriageable women. In a 2004 essay, Bonnie MacLachlan summarized this cultural phenomenon: “The essential eroticism of Greek nymphs [brides] was combined with two other important features, the chthonic and the playful.” The word ‘chthonic’ is an adjective relating to the Underworld, tying girlhood and maturation to death. Sexuality, the life-death cycle, and freedom — these themes recur in stories about young women coming of age. Though our protagonist is a full-grown woman well into her adulthood, she has to resolve her dissociation and realize her capability. The dream gives her the space to process her feelings about her relationship and how it impacts her in various ways, like her gender and sexuality.

In terms of the mv’s narrative and visuals, they share traits with the Beauty and the Beast (BatB) template, which relates back to nymphs through stories like that of Persephone. The Beast character embodies the Beauty’s latent desires and general darkness, as he represents her animalistic, masculine side. He is the personification about all of her fears towards growing up and seeing herself clearly. In her 1989 treatise, Beauty and the Beast: Visions and Revisions of an Old Tale, Betsy Hearne outlines the fairy tale:

[H]er isolation at the palace is a vision quest[.] […] Beauty’s [story] is the journey to the underworld[.] […] […] Beauty’s movement from civilized society to a secret castle parallels her progression from the outer public realm to the inner personal one. […] The garden and moonlit landscapes characteristic of many versions (along with the castle mazes and magic chests that enlarge with wealth contained within) summon strong images of female sexuality. Beauty must fully accept her innermost nature before she can love fully. (p. 132, 150)

The theme of looking, enforced by mirror motifs, runs throughout BatB stories, and its influence shades the song and video, with lyrical references to seeing and Brittany’s watchful reflection.

In DYED?, Brittany transitions from North Carolina to Iceland, thus from her consciousness to her subconscious, by stepping through a doorway. It’s an age-old symbol of liminality and change; she walks into a garden of her imagination. Her landscape evokes a woman’s sexuality as well, though in a more wild, archaic sense. She navigates the rocky terrain by a waterfall, treks alongside a river, and sprints across black shores, the spray at her feet. Water and stone dominate the landscape.

This video’s narrative is not a Batb storyline but has some of its elements: a woman’s coming-of-age catalyzed by a relationship. In BatB stories, Beauty “dies” early on (socially and familially), while the Beast’s transformation often comes towards or exactly at the end. Our character “dies” at the climax rather than towards the beginning, more in line with the traditional hero’s journey. Her gray, beaded dress and fur coat remind me of a funeral shroud, of the elaborate burials associated with Scandinavian cultures. Her awakening is thus a rebirth, as she has finally chosen herself. Unlike the fairy tale, hers is a lesson in self-love, achieving self-actualization without an external force. Specifically she achieves, in terms of Jungian psychology, what scholars refer to as ‘individuation’, a concept that bridges psychology and literature: “[I]ndividuation can be defined as the achievement of self-actualization through a process of integrating the conscious and the unconscious.” Overall, her journey through Iceland gives Brittany the space to process her relationship while forcing her to feel the fullness of her pain, the video’s structure rooted in familiar narrative structures.

Expressions of Womanhood:

DYED? conveys a rich heritage based in women’s storytelling, building on a literary tradition of stories about girls and young women coming of age in a liminal and/or dreamlike setting. Examples include Persephone in the Underworld, Alice in Wonderland, Dorothy Gale in Oz, and Sarah Willians in the titular labyrinth from the 1984 film. The latter also ties back to BatB, as Sarah’s adversary is an animal husband character, demonstrating that the trope can apply to coming-of-age stories not centered around an endgame romance. Though I typically don’t care for ‘it was actually a dream’ storylines, DYED? succeeds because the mv acknowledges the gravity of the song. When done right, a fictional dreamlike setting makes sure to give the story time, providing space for character growth and thus resolution. It ultimately comes down to whether or not the dream allows for full emotional weight; that even if what happened was ‘fake’ the emotions aren’t, and the experience changes the protagonist, inspiring her. In this case, Brittany is inspired to finally leave and put herself first. In classic storytelling, we see a similar oneiric-inspired progression with Dorothy Gale, who realizes, even though she only dreamt everything, that, “There’s no place like home.”

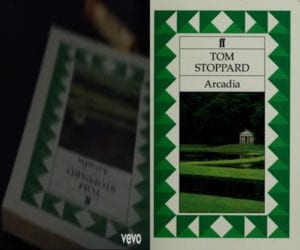

While reviewing the BTS video, I zeroed in a book that had been placed near Brittany’s phone (t. 00:37). The scene required specific prep work in order to film Brittany falling into bed; the crew actually raised the bed and filmed horizontally, pushing Brittany backwards with a dolley. Eric mentions that they had to “fabricate everything” (t. 00:32), meaning that this prop was intentional. I traced the cover through Google Images and discovered that it matches the first edition of Arcadia, a 1993 play by British playwright Tom Stoppard. Its Wikipedia page (at the time of this article’s publication) summarizes the play as “concerning the relationship between past and present, order and disorder, certainty and uncertainty.” Arcadia definitely has a dreamlike quality. The play alternates between two timelines, linked by recurring props, and its final act culminates with the two timelines merging, multiple characters from both sharing the stage. As an act of thoroughness, I watched a version posted to YouTube. The production consisted of middle and high schoolers, with some of its more mature elements cut, but it still gave me a general sense of the story.

For one thing, the title fits into DYED?’s themes as ‘Arcadia’ refers to a type of wilderness, which became a literary and artistic symbol for environmental purity, paradise, and freedom. One of Arcadia’s central characters is Thomasina Coverly, a teenaged girl and child prodigy in mathematics and science. Her budding sexuality runs alongside her budding curiosity for the universe’s inner workings, and her development also happens in time to her mother renovating the grounds of their estate. The play opens with her inquiring about the meaning of “carnal embrace”, embarrassing her older tutor Septimus. Ignoring his attempts at dissuasion, she also investigates the laws of thermodynamics. Sexuality and nature are further intertwined due to Arcadia being the home of Pan, a nature god and satyr. In Greek mythology, satyrs were known for their voracious sexual appetites and for pursuing nymphs and young mortal women. The original playboy Lord Byron is a referenced character, never appearing on stage but still causing trouble, Thomasina briefly infatuated with him. Another young woman from the modern timeline parallels Thomasina, and she is seduced by a licentious professor who is researching Byron. In addition, Thomasina and Septimus’s relationship finally culminates in a romantic dance, hinting towards burgeoning feelings, right before her seventeenth birthday. Right before she dies in a house fire. Their last conversation even references a candle. As SparkNotes puts it, “Thomasina is ironically engulfed in the flame that she once seemed to understand better than anyone.” In Stoppard’s play, sexuality destabilizes paradise.

So Arcadia shares themes with DYED?, the book a nod to the stories’ connection. The elements don’t match up though. As I mentioned earlier, water and stone dominate the Icelandic landscape. Water and earth are feminine elements, respectively associated with fluidity and stability. Brittany is in constant motion, coming up against her cold, impassable lover. She is also grounded and seeks to grow, to build a future. Water though is the catalytic element, the near-fatal end result of her mad chase off a cliff. In his essay, “Underwater Women in Shakespeare on Film”, Charles S. Ross analyzes the use of water as a symbol. He writes,

[T]he association of water and the social oppression of women has long been a symbol and theme in Western literature and more recently in film. […] In recent Hollywood films the trope of the underwater woman offers a generalized symbol of oppression that goes beyond a specific problem […] to suggest a wider need for women to move outside the confines of the world in which they find themselves. The trope itself is a variation of the ritual of bathing to ride one of one’s earlier self or the stigma of the world[.] (p. 36, 47).

The prevalence of water in the dream, helping to form Brittany’s ideal world, indicates to me that the water isn’t a negative symbol for her. That it’s multifaceted and representative of her passion for life. Ross further cites, “a connection for women between drowning in the sea and survival,” (p. 37); he summarizes it connection to “sensuality and oppression” (p. 38). From the sociological side, MacLachlan’s analysis of Greek brides also notes the sensuality of water in young womanhood and its transitional associations. Delta Rae is not telling a cynical story dissuading a person from falling in love, from dreaming about the future. The mv instead imparts an aesthetically-charged piece about the importance of not wasting one’s love on a person so opposed to reciprocating. Her love interest defies gravity, disinterested in working on their relationship and to opening himself to risk through vulnerability. His coldness goes against nature, and though he may appear supernatural in the dream, free from consequences, he does wake up alone.

The video’s themes kept pulling me down towards these stories about young women and their emotionality. While reading different texts as research for this article, I began to think about Shakespeare’s Ophelia out of the blue. My subconscious was poking at me so I began to read about a theory I had seen in passing months earlier. (Coincidentally, Stoppard wrote Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, a play that focuses for the most part on the titular characters outside the Hamlet story, dealing with themes of the absurd and existentialism.)

Though not recognized by many mainstream academics, including scholarly annotations of Hamlet, there exists a well-supported theory that Ophelia was pregnant throughout the play and tried to give herself an abortion. Several flowers from her infamous speech are abortifacients. Notably, she keeps rue for herself, and rue was and remains one of the most effective abortifacients in herbal medicine. The subtext in her speech would not have been lost on Shakespeare’s audience. Alicia Andrzejewski examined Ophelia’s rue and analyzed another scholar’s work on herbal birth control and the related medical literature, writing, “These admonitions, these shrill warnings, support Riddle’s argument that women taking their fertility into their own hands, through the use of herbs and plants, was common practice despite male physicians’ attempts to obscure and police this knowledge.”

A screenwriting blog also highlighted some possible double entendres related to pregnancy that appear throughout Hamlet. In an article on Ophelia’s musicality, Kendra Preston Leonard examines how men, while directing adaptations, erased Ophelia’s agency and sexuality by reducing her songs, further removing modern audiences from the sexual subtext. Traditional productions would have Ophelia sing several songs that were popular tunes for Shakespeare’s time, including ‘To-morrow is Saint Valentine’s Day’. That specific song details a woman being abandoned by her lover after he seduces her, disgusted by her sexuality. He shames her for giving in to her desires.

This theory recontextualizes Ophelia’s descent into madness and eventual suicide. It deepens one’s understanding her relationship with Hamlet (and affirms my theory that Hamlet is a college f*ckboy). She dies after falling from a tree into a brook, drowning. While an illegitimate pregnancy and abortion could have caused an accidental death, I still lean towards Ophelia having committed suicide as an expression of her pain — grief, heartbreak, and possibly shame from a pregnancy — and as one final act of agency.

My hyper-associative and hyper-comparative brain kept bugging me about how I made this leap. There had to be something more than just heartbroken young women and water for my subconscious to be gunning so hard. So I rewatched DYED? to see where I may have made that initial connection. It appears towards the end of the video. As Brittany falls to the water below the scene transitions using rippling bed sheets to represent the wind and sea. When she lands on the bed, she holds her arms up beside her head in an awkward position, her elbows bent. It’s a split second, but it’s there. The pose recalls Sir John Everett Millais’s Ophelia, an iconic painting reproduced throughout pop culture. That depiction of Ophelia has her holding her arms in a similar position as she floats in the water, presumably drowned or about to drown. So, Brittany and Ophelia’s stories speak to one another through related imagery and themes of gender dynamics. Overall, DYED? relays a redemptive, Ophelian story in which Ophelia is able to get the hell out and save herself, without sacrificing her sensitive, vulnerable nature.

To return to the falling scene, musically it centers around the song’s third verse, an emotionally-charged section that reveals the narrator’s growth:

Do you ever dream when the nights get lonely?

You’re gonna wish that I was there

Do you ever dream how it’s gonna hurt baby

When there’s nobody that cares

About the stories that you tell?

Do you even get that far?

‘Cause I’ve been living in this moment

And it’s all falling apart

Not only does she acknowledge her worth (him wishing she was there), she acknowledges that she had been playing by his rules, going along with him, by “living in [the] moment”. She admits that she blinded herself to her needs, focused on the problems but not knowing how to act. Within the video, this verse starts as she appears on the cliffs, spotting her lover again. (Angela recognized this location as Reynisfjara, a well-known beach with black sand and a reputation for danger. Several tourists have drowned there in recent years.) The verse follows after an extended section that consisted of instrumentation and backing vocals, Brittany no longer singing or looking into the camera. The more she acknowledges her pain and confusion, the more she becomes in touch with her emotions, breaking through the dissociation. So when she spots her lover, she experiences a rush of feelings: despair, confusion, and fear. Through this dreaming, Brittany experiences enough of the grieving process that when she wakes up, she awakens with clarity and resolve. She’ll keep dreaming, but she won’t sleepwalk through life with her love interest.

When trying to articulate feral feminism, I go back to that original meme: “[T]he highest feminine ideal is the ability to be feral in peace[.]” Feral implies to be unrestrained; it conjures images of emotional fullness. You can want something, but you can’t want it too much. DYED? expresses the tension in wanting as a woman. Wanting undoes Thomasina Coverly and Ophelia, and it almost undoes our heroine. In a wonderful essay on disordered eating and horror films, Laura Maw writes, “[B]eneath the resistance and suppression of appetite is something wild, something demanding, something terrifying.” To give in to appetite, to allow for wanting in any way, can be a way of giving in to change, tapping into primordial places we haven’t been able to yet face. Feral feminism acknowledges that appetite — for warmth, for love, for life.

My previous Delta Rae article mentioned grotesqueness as a possible feminist approach to boundaries and aesthetic. So maybe feral feminism is simply grotesque wanting — wanting that transgresses boundaries because it’s a woman active in her desire, maybe reveling in it. In 1979, Lucille F. Newman analyzed Ophelia’s flowers, writing, “Ophelia’s speech was capable of conjuring up images of pollution in the mind of the hearer and suggesting a dramatic change in her character from a former state of purity,” (p. 228). For as long as there has been misogyny, ‘purity’ as a concept has been used to shame women for enacting their bodily agency. Oppression swallows up sensuality and writes off a woman as broken. By using feral feminism to read a text, I am rejecting this binary interpretation of purity as a have-lost phenomenon, instead seeing purity as an integral element to all people. A circle based on the idea that a person can find herself, again and again, spiraling back to an inner truth found in the woods and under the full moon.

Thomasina demands her tutor to support her curiosity, whether that be in science and mathematics or dancing. Fire gets her, but her theory lives on in Septimus’s memory and in her journal. Ophelia demands love and since she cannot have it, she demands justice through remembrance. She calls out the court’s misconduct and cruelty before she ends up in that brook. And Brittany does not drown in Icelandic waters, her lover’s coldness cannot subsume her. She demands to know if he dreams because she won’t stop. Her story concludes with her hand out the window because she holds on to her innocence, the simple wish to feel the wind on her skin. Feral feminism allows for a pure sense of heart while one also struggles with grief and messiness, structured around the cycle of nature: birth, death, and renewal.

Conclusion:

On New Year’s Day, Delta Rae released their lead single, which they described as a “sex-positive, 80s vibe anthem”, noting how the song supported them through the past year. In two months, the band’s new studio album will also drop, and they have made clear that all their music belongs to them. Their repeated statements about owning their work and independence resonates in today’s music culture.

As I mentioned in my previous Delta Rae article, the band shares similarities with Taylor Swift, both musical acts having recently left BMLG. Swift discussed the industry for an interview with Music Week. She referenced “creative constraints” and a toxic work environment, praising her new label for its support: “It’s like when people find ‘the one’ they’re like, ‘It was easy, I just knew and I felt free’.” She compared her record label ties to relationships, and we see that parallel with Delta Rae, whose creative rejuvenation started by finding personal catharsis through art. Back in the spring, Swift had also mentioned that there were undiscovered Easter eggs from her ‘Look What You Made Me Do’ mv (t. 2:52). Swifties, of course, freaked out, wondering what we had missed, and in the fallout from Swift’s exposure of BMLG’s toxicity, fans went back to the video. Fanblog officialtaylornation pointed out a clip of Swift holding two motorcycles in hand, comparing it to Big Machine’s logo of a red car. The image had never made sense to the fandom, but now it clicked: Swift carried Big Machine herself, helping to build the label to what it is now. (This past week Swift liked a Tumblr post that referenced this interpretation.) I wanted to point this out because of DYED?’s ending.

The car that Brittany takes is a red truck.

Did Delta Rae implant an Easter egg, foreshadowing their decision to leave, or did the whole creative process around the song and video inspire them? They hinted at this in a tweet, reflecting on DYED? and the residency they subsequently launched, describing it retrospectively as their “first rebel step.” And that’s what ultimately matters: that they got out.

A year ago today we released “Do You Ever Dream?” and launched The Revival — our 16 week residency in a haunted chapel we built by hand. In retrospect, this was our first rebel step toward independence. No turning back ✨ pic.twitter.com/rfFiikkKwQ

— Delta Rae (@DeltaRae) September 5, 2019