Introduction:

I can still remember where I was when Taylor Swift won Video of the Year at the fan-voted CMTs for her ‘Mine’ music video. It was June 8th, 2011, the sun still pouring in through the windows, and I was visiting some relatives in Fortworth, Texas, hundreds of miles from my abusive parents’ panopticon. My Texan relatives humored me and gave me control of the TV so I could watch the ceremony. For the next year or so, I went through my Country Music Television (CMT) phase, watching the channel’s morning line-up, picking up new songs to add to my phone, and absorbing behind-the-scenes footage and interviews on the filmmaking process. I developed this interest separate from my cinephile parents, a way for me to safely and independently cultivate a love of film. Now I will be writing about these videos professionally… It’s funny how things come together.

This piece will be the first in a series known as ‘Women in Music Videos’ (WMV), which I will write sporadically, as I engage with current and older pop culture. WMV centers around the songstresses who hold the camera’s gaze, and I will approach the artist and video a little bit differently every time. Some articles will delve heavily into the lyrics and their relationship to the film, examining the video’s story. Some articles will be more comparative analysis, taking into consideration the artist’s past work, especially if a certain video speaks to or connects to the main piece at hand. An article or two may also go into professionally recorded live performances that aesthetically stand out to me. My goal is to bring scholarly attention to this important and influential medium.

In this specific article, I will attempt to summarize Swift’s history as a filmmaker and contextualize it within her whole artistry, saving the meatier analysis for future pieces. (Swift’s work will comprise its own miniseries within WMV.) Her cinematic creativity fascinates me as a film nerd — I even wrote a section about her music video work for her Wikipedia page — and I can’t stop talking about it. Swift’s budding work as a filmmaker reflects her commitment to lyricism and her fascination with narrative, both the narrative in her songs and the narrative of her life.

Before I delve into that though, I want to lay some groundwork on music videos that will resonate in every WMV article. And since I will be citing several videos, I will cite them as (t. number) in reference to the timestamp, because academic citations haven’t caught up with the digital age.

The Medium of Music Videos:

Filmmaker Matheus Siqueira traces some of music video’s earliest history to 1920s short films that had been blended with live-action footage of performers. (This stemmed from the development of sound and the rise of ‘talkies’.) These kinds of short films evolved throughout the following decades as more accessible technology allowed for more experimentation. Siqueira notes that in 1965 The Beatles’s ‘We Can Work it Out’ was the first known music video to be broadcast in full on TV. Then, the following year the band collaborated with a director in order to “start exploring more options in the cinematic language realm.” In 1981, the Music Television channel (MTV) debuted, followed by Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’ two years later. Overall, the second half of the twentieth century saw an evolution that led to the music video as we know it.

Filmmaker Matheus Siqueira traces some of music video’s earliest history to 1920s short films that had been blended with live-action footage of performers. (This stemmed from the development of sound and the rise of ‘talkies’.) These kinds of short films evolved throughout the following decades as more accessible technology allowed for more experimentation. Siqueira notes that in 1965 The Beatles’s ‘We Can Work it Out’ was the first known music video to be broadcast in full on TV. Then, the following year the band collaborated with a director in order to “start exploring more options in the cinematic language realm.” In 1981, the Music Television channel (MTV) debuted, followed by Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’ two years later. Overall, the second half of the twentieth century saw an evolution that led to the music video as we know it.

Siqueira concludes with what he referred to as the ‘YouTube era’, an ongoing period that started with YouTube’s creation in 2005. From my own web dives, indie and up-and-coming mv directors also often post their work to Vimeo, a platform competitor to YouTube with more experimental and obscure films. It functions as a place for directors to curate an archive and/or a portfolio of their work.

As with Hollywood and feature films, it’s assumed that the music video industry also features a shortage of women directing, and that follows from the credited names I’ve seen over the past decade, though I couldn’t find a specific statistic. In a 2015 interview, high-profile mv director Hannah Lux Davis described the behind-the-scenes process that leads to filming:

The record label works with a video commissioner to decide what they’re looking for in the video and how much they’ll spend. From there, an email is sent out to the directors they’re interested in that contains the song, a time and place for the shoot, and a creative brief. […] Once a director gets that brief they’ll start to make a treatment: that’s a pretty PDF with lots of gorgeous pictures that paint the picture of what the video will look and feel like.

Davis went on to describe the collaborative process between director and artist. At its core, a music video is a commercial for the song and for the artist herself, presenting a packaged version for public consumption. A good director will be open to feedback from the artist regarding the treatment, listening to ideas ranging from concepts to costumes. If an artist feels comfortable with a director and their style and connection, she will probably work with them again. Thus a collaborative relationship can develop, the director’s cinematic quirks and motifs bleeding into the artist’s iconography.

In an era of streaming, YouTube remains more accessible and democratic than other streaming sites. The site doesn’t keep its content — even its original shows — from viewers behind a paywall. Anyone with Internet access, even children, can watch professional and amateur videos, and speaking personally, I first dove into YouTube because of music videos. As a channel, MTV now focuses on producing teen melodramas and reality shows, leaving YouTube as the major platform for music videos, including archiving the old. Its accessibility has huge potential on culture. In the 1980s, folklorist Alan Dundes edited Cinderella, a Casebook, a collection of essays about the fairy tale. Fellow folklorist A. K. Ramanujan provided ‘Hanchi: A Kannada Cinderella’ for the book, and for its introduction, he wrote:

Though the typical structures are common, the realized tale means different things in different cultures, times, and media. It is regarded here not merely as the variant of a tale-type, a cultural object, a psychological witness (or symptom), etc., but primarily as an aesthetic work. I believe that, in such tales, the aesthetic is the first and the experienced dimension, through which ethos and worldview are revealed. The other kinds of meanings (psychological, social, etc.) are created, and carried, by the primary, experiential, aesthetic forms and meanings. (p. 260)

This idea of “an aesthetic work” applies to music videos in many ways. So many videos focus primarily on lighting and color, placing the artist front and center; the music video presents a certain image, intentionally or not, that impacts how the viewers see themselves and the artist. Like with full-length films, the medium has often reflected and reinforced the commodification of women as sexual objects. Other social issues, such as gender, race, and sexuality, have intersected with this commodification and fetishization. Swift has become more involved with the production of her music videos, in part to better convey her stories and her personality, though she is not the only major pop act to do this. Lady Gaga, Beyoncé, Hayley Kiyoko, and Halsey also have moved behind the camera as directors and co-directors, infusing more of themselves into their art.

Being a Swiftian Culture Critic:

With all of that in mind, there exists this tension when it comes to analyzing Swift’s work. I’ve followed her career for 10 years, and media outlets have often reduced her lyrics to ‘guess the subject’, thus reducing her art to gossip fodder. When it comes to interpreting someone’s work, the process typically exists between the frameworks of auteur theory and Death of the Author, both of which originated in 1960s French culture. The former focused specifically on the French New Wave, a cinematic movement that aimed to distinguish filmmaking as its own artform, shaped by the directors and their bodies of work. The theory singularizes the director as the creative force behind a production, and in popular culture, it has come to represent the pretentious, narcissistic, and edgy white man who infuses his sexual desires into the screen. In a video on the cult-disaster movie, The Room, YouTube-based media critic Kyle Kallgren cites Pauline Kael’s essay refuting the theory, explaining that, “Following artists who repeat their own work, Kael argues, distracts from the artistry of filmmakers who experiment with form, narrative, and genre,” (t. 4:19-4:23).

This can not apply to Swift’s artistry as her career centers around personal and generic evolution. Not only did she transition from country to pop music, but she has also dabbled in various genres and subgenres like dubstep, trap, and EDM. In addition, though she drives her songwriting and usually maintains a small group of collaborators (which I will discuss in more detail later), she eagerly and openly experiments with different writers and producers to push herself and to learn from them. She controls her music without being controlling, in contrast to the domineering auteur.

In regards to Death of the Author, this framework encourages the reader to disconnect the author from their text entirely. Whatever they may say about their text need not apply. J. K. Rowling’s tweets are a recent example of why ‘Death of the Author’ helps to maintain a text’s purity, separate from an author’s changing opinions and biases. Lindsay Ellis, another media critic on YouTube, dissected Death of the Author and cited Michel Foucault as a major proponent, who was more radical about ‘killing’ the author than the theory’s creator, Roland Barthes (t. 16:14-17:30). Foucault’s dismissal of the author’s personal identities reflect the problem with ‘Death of the Author’. It assumes that a neutral experience exists for readers and for a text, as if people can’t bring their personal biases to interpreting a work. The framework strips a text of its sociohistorical context, which disadvantages lesser-known voices and perspectives, especially when privileged, more powerful people have stolen the intellectual and creative works of the marginalized. In a later tweet, Ellis clarified that, “[O]ur thesis was that neither of the two extremes really work in their pure form,” and that is the tightrope I will walk. Similarly, Swift has always been open with fans about her personal tribulations, yet she also encourages Swifties to apply the songs to their own lives.

I do not want to dismember Swift from her own narrative, as the media has. Established music critics like Rob Sheffield, Brian Mansfield, and Caitlyn White have mastered this balance, providing valuable insight into her career, and their analyses will sometimes influence my WMV pieces.

The Lyricism and Aesthetics of Taylor Swift:

In regards to Swift as an artist, her writing is central to her psyche and her career. She professionally originated at Sony/ATV, a music publishing company, as the youngest songwriter in its history, Swift developed a storytelling-style in the tradition of country music, an indelible trait in her catalog. She was fourteen at the time. And so, there is at least one song on every album that references her role as a writer, as her relationship with her own life narrative is a recurring theme. In an insightful blog post, the blogger articulated a point that the cited critic couldn’t quite get:

[H]er songs have continually shown a concern with and a performance of the unreliability of narrative. As Alex Macpherson points out, the first lines of her first single announce[s] as much (“He said the way my blue eyes shine/put those Georgia stars to shame that night / I said that’s a lie”)[.]”

That first single, ‘Tim McGraw’, was the lead track to her debut, self-titled album. She wrote the album over four years, starting when she was twelve. Its closing track, ‘Our Song’, ends with Swift writing the aforementioned song, and in a relatable detail, she does so on ‘an old napkin’ that was at hand. Her sophomore album, Fearless, pushed her into international stardom, and it remains the most awarded album in country music history. Fearless also codified her idealization and deconstruction of fairy tales that frequent her personal lyrical tropes, reflecting the tension in developing a mature worldview while fighting for innocence. Trying on characters, exaggerations of her persona, reflecting the multiplicity of a girl’s identity — then a woman’s — is the core of her work.

And so, to be stripped of one’s narrative is a violation of the self, one which she has experienced because of toxic relationships and because of years-long media slander and slut-shaming. It began with the debut-era ‘Cold As You’, a song about walking away from an unfeeling, cruel partner who “come[s] away with a great little story/of a mess of a dreamer with the nerve to adore you.” After Fearless, having been thrust into the limelight and into her wildest dreams, her understanding of her career began to seep into her lyrics, starting with ‘Mean’. That song was a response to the vicious criticisms about her vocals, particularly one bad performance. ‘Mean’ came from her third album, Speak Now, which she wrote without any co-writers and did so as a response to doubt over her songwriting capabilities. Her 2012 song ‘The Lucky One’ addresses her fears about her career through a semi-fictionalized story about Swift’s musical inspirations — a conglomeration of the singers who eventually disappeared from the Hollywood machine in order to survive. Her first full pop album, 1989, then addressed the serial dater rumors and image, satirizing the character in ‘Blank Space’.

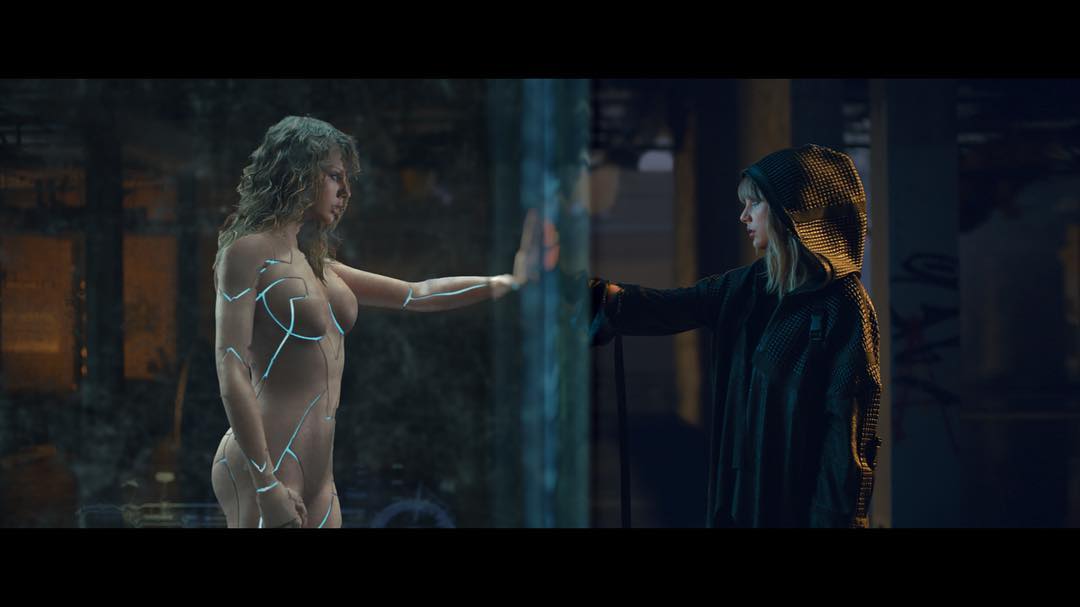

Her sixth album, reputation, further addressed this dissonance, with its marketing designed to mirror the polarity: the petty, drama-loving robot spewed by the tabloids, contrasted against a heartful, warm woman deeply in love with her partner. For example, critic Frazier Tharpe praised the album’s fourth promo single ‘Call It What You Want’ at the expense of the earlier three, writing that, “[I]t ditches the revenge narrative to great effect,” revealing his own biases against Swift. reputation’s lead single ‘Look What You Made Me Do’ did embody rage, obsession, and self-preservation, yet all three subsequent promo singles focused on love. ‘Ready For It’ explored the theme of “partners in crime” while ‘Gorgeous’ described a frustratingly attractive love interest. Arguably ‘Ready For It’ acknowledged the revenge narrative by acknowledging her man-eating reputation, but that was the extent of it.

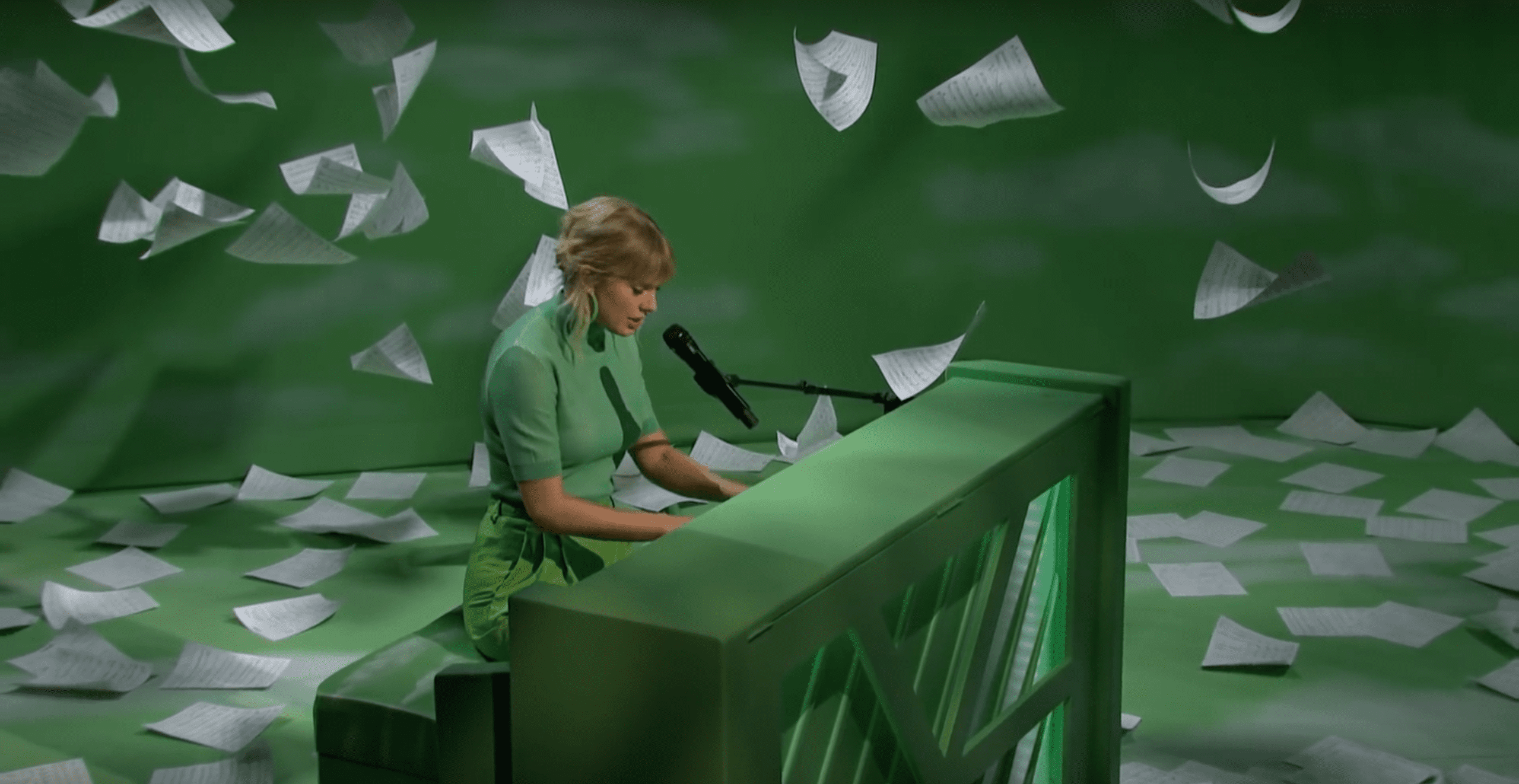

Overall, her lyricism permeates her personhood and her career. While being considered for jury duty, she reportedly said that she was a songwriter when asked about her occupation. Swift has also written about the craft: In 2018, she interviewed model and memoirist Pattie Boyd about having been a muse for George Harrison and Eric Clapton, and this spring she penned an essay for Elle U.K. on songwriting. This past week she appeared on Jimmy Fallon and then performed ‘Lover’ on SNL. On Fallon’s show, she joked about being the only writer on the song, explaining, “I love the song ‘Lover.’ […] It’s a song that I wrote alone, and somehow those are —I don’t know. […] I find it funny thinking about if I were to have, like a […] party for all the songwriters on that song. […] ‘Cause it would just be me,” (t. 2:41-3:03). (The joke is also a meme she picked up from the Swiftie fandom.) For her SNL performance, she stripped the song back to a piano the instrument on which she originally wrote ‘Lover’, surrounded by a blizzard of music sheets.

With all of that in mind, Swift has a documented love of cinematic storytelling, fandom culture, and easter eggs. She named her three cats after TV and movie characters. In 2014, she wore a shirt that referenced an obscure, old Tumblr/Swiftie meme. Two months ago she blogged for half an hour about her love for Paddington Bear. She also has been using social media to connect with her fans, going all the way back to MySpace in the mid-2000s, and frequents Tumblr, commenting on Swifties’ analyses and fan creations. Swift is a fellow fangirl, plain and simple. And her obsession with pop culture helps to explain her success at marketing her music, because not only does she listen to Swifties about their interests, she has had similar experiences. Her passions enrich the music, ballooning sounds into a soundtrack for a whole universe. She then curates an aesthetic to reinforce and further develop each album’s psychological landscape, comparing the imagery and colors to a “mood board” (t. 14:41-14:44). As Ramanujan would say, her “ethos and worldview are revealed” with each album, peeling back another layer as listeners chart her personal development.

It also factors into how she chooses her wardrobe and hairstyles since she leans into change. Due to her relationship with aesthetics, I can usually pinpoint a picture of Swift to within a two-year timeframe. She embraces humanity’s fluid nature, how we all go through phases of life. As part of a photoshoot for Sony in 2012, she was interviewed about cameras and compared visual arts to music, explaining:

I think photography and music are both setting out to accomplish the same thing. With photography and with music, you’re trying to capture a moment the best way you possibly can so that you can look back and remember it later. […] You’re trying to capture how it looked and how it felt to be in that moment. (t. 0:02-0:26)

Naturally, she also links music and film. When selecting a co-director for her ‘You Need to Calm Down’ music video, she chose Drew Kirsch for his color-blocking skills (t. 31:35-31:46). She uses visual aids like colors as she uses certain production sounds to shape the stories in her song. Her transitioning into writing and co-directing her mv’s reflects a natural progression, as the medium already blends forms of narrative communication (sound and sight).

Music Video Involvement:

For her first two albums, the related mv’s followed the standard procedural where the director handled treatment and filmmaking, but even then she maintained a level of control. In a behind-the-scenes video (BTS) on her mv for ‘White Horse’, the second single from Fearless, she discussed actor Stephen Colletti, who she’d chosen to play her love interest. She explained that, “I’ve had a hand in picking most of my video guys because it’s a really important thing, like they each have to stand for something different and represent different things,” (t. 1:26-3:20). She also paid for her music videos herself, funding them from her touring revenue.

Due to the opaque nature of mv credits, it can be difficult to distinguish between writing the actual treatment and developing the concept. In most music videos, the director isn’t also mentioned on screen, though some claim their work, and some artists across genres now cite the director in the video description. This focus on the director is reminiscent of the auteur theory, obscuring all of the people involved in the production, and though Swift has become clearer on the production companies who handle her music videos, she too reinforces this opaqueness with her music videos as well. I can see her improving on this front as she advocates for accreditation. For example, Todrick Hall a musician, choreographer, and close friend, helped Swift with her ‘You Need to Calm Down’ music video, and she made a point of giving him co-executive producer credit. Normally she doesn’t cite the executive producer in a video, but in that music video, it blazed across the screen.

To date, she has four co-directing credits on her music videos. (She is considered the director for music videos like ‘The Best Day’ and the vertical version of ‘Delicate’, though I consider those videos separately since they weren’t official singles and were only compilations of personal videos she filmed.) She co-directed ‘Mine’ in 2010 with Roman White, ‘ME!’ with Dave Meyers, and ‘You Need to Calm Down’ and ‘Lover’ with Drew Kirsch; the latter three all within the past six months. ‘Mine’ was the lead single for Speak Now, and that era included her venturing into treatment-writing as well. She wrote the treatments for two of her 2011 music videos, ‘Mean’ and ‘Ours’, both directed by Declan Whitebloom. Notably, she described them as “storylines” (t. 00:32-00:43). Regarding the ‘Mean’ music video, Whitebloom said, “She was keenly involved in writing the treatment, casting and wardrobe. And she stayed for both the 15-hour shooting days, even when she wasn’t in the scenes.” Her music video involvement then returned to standard procedure until the 1989 era, and she began to collaborate with director Joseph Kahn, him having director’s credit while she filled other roles. For example, she created the concept for her ‘Wildest Dreams’ music video (thus likely writing the treatment) and produced her ‘Bad Blood’ music video. For her ‘Blank Space’ music video, she also collaborated with American Express, releasing an interactive app related to the video. She then won an Emmy for ‘Outside Interactive Program’ with starring and executive producer, achieving half of EGOT (Emmys, Grammys, Oscars, and Tonys) at twenty-five.

Between 1989 and reputation, Kahn directed eight of her music videos. In an interview, he had this to say: “It was literally one of the first times I felt that someone actually spoke the language of filmmaking that I’ve been doing over the last 25 years.” He has always supported and defended her online, though they no longer collaborate. Swift now owns the rights to her songs and videos in their entirety, and this likely affected her decision to stop working with him.

I think her involvement leaned more towards directorial than not, regardless of accreditation.

In general, the fandom agrees that Swift should have been credited as a producer on songs that she wrote with Max Martin and Johan Shellback. The duo are Swedish pop hitmakers, and she collaborated with them from Red through reputation. She began co-producing all of her songs on Fearless and continued that trend until Red, when she sought out different collaborators as an educative process. Of the new producers on that album who did not share co-producing credit, she only continued working with Martin and Shellback, and on 1989 and Lover, all of her new producers gave her co-producing credit. It’s a glaring omission, as evident in her ‘Making of a Song’ series from the reputation era. That series included clips she recorded of herself and her co-writers in the studio, and she makes suggestions regarding vocal effects and leads the direction of the sounds. For example, she recorded a brilliantly weird vocal in the middle of the night, and she brought it to Martin and Shellback, describing the situation as “trying to explain the production” to them. Martin couldn’t provide an instrument to replicate the sound so he pitched her voice down. These collaborators accentuate her raw materials and ideas in her areas where she has less experience, hence why her co-producers and co-directors have lead credits in those fields while she always has lead writing credit.

In general, the fandom agrees that Swift should have been credited as a producer on songs that she wrote with Max Martin and Johan Shellback. The duo are Swedish pop hitmakers, and she collaborated with them from Red through reputation. She began co-producing all of her songs on Fearless and continued that trend until Red, when she sought out different collaborators as an educative process. Of the new producers on that album who did not share co-producing credit, she only continued working with Martin and Shellback, and on 1989 and Lover, all of her new producers gave her co-producing credit. It’s a glaring omission, as evident in her ‘Making of a Song’ series from the reputation era. That series included clips she recorded of herself and her co-writers in the studio, and she makes suggestions regarding vocal effects and leads the direction of the sounds. For example, she recorded a brilliantly weird vocal in the middle of the night, and she brought it to Martin and Shellback, describing the situation as “trying to explain the production” to them. Martin couldn’t provide an instrument to replicate the sound so he pitched her voice down. These collaborators accentuate her raw materials and ideas in her areas where she has less experience, hence why her co-producers and co-directors have lead credits in those fields while she always has lead writing credit.

Because of the way that Kahn described her involvement, I think she was more of a co-director than not. In a 2015 interview (published in 2017), he described their process and relationship positively:

We talk very deeply about every project that we do[.] […] We have a complete discussion. These are true collaborations — it’s not like, ‘Hey Joseph, here’s a song and come back and tell me what to do.’ It’s not like that at all. We talk about every shot, we discuss every set-up as we’re doing it and there’s nothing that happens without literally both of us putting our brains together about it.

Swift’s burgeoning creative pursuit as a filmmaker reflects her career-long commitment to creating and controlling her art. It is an extension of her commitment to creators’ rights, which she has endorsed as a labor activist for years.

Labor Activism:

Swift’s journey as a singer centers on her creative freedom. At fourteen, she walked away from a deal with music-giant RCA and became the first signed artist for new indie label Big Machine. Its founder, Scott Borchetta, promised full support of her songwriting, and she saw him as a father figure, staying loyal to him even as he began to exert control and resent her business skills. (Many Swifties even theorize that one of the reasons she remained politically silent for so long was connected to Big Machine’s grip and Borchetta’s documented conservative politics.)

She has always supported smaller artists, bringing them on tour and including indie artists on her playlists, many of whom weren’t verified on social media. She posts about new songs and movies on InstaStory, such as highlighting Ciara’s new album and Ruby Rose’s Batwoman premiere. That being said, her more politically-inclined support started to take shape specifically in 2014. She pulled her music from Spotify that year due to its gross compensation of artists, influencing the company’s payment model, and did not return until 2017. In 2015, she then penned her infamous Apple Music letter, calling the company to task for its refusal to pay creators during its three-month free trial period. She explained:

This is not about me. Thankfully I am on my fifth album and can support myself, my band, crew, and entire management team by playing live shows. This is about the new artist or band that has just released their first single and will not be paid for its success. This is about the young songwriter who just got his or her first cut and thought that the royalties from that would get them out of debt. This is about the producer who works tirelessly to innovate and create, just like the innovators and creators at Apple are pioneering in their field…but will not get paid for a quarter of a year’s worth of plays on his or her songs.

Within hours, Apple submitted to Swift and changed their policies. She continued her labor activism as a founding supporter of the Grammys’ Producer and Engineering Initiative, a program dedicated to reducing the gender gap in those fields. On her reputation tour, every night she dedicated her song ‘Dress’ to Loïe Fuller, a mother of modern dance and influential businesswoman whose lawsuit in the 1800s influenced copyright law until the 1970s. Last November, when Swift’s contract was up with Big Machine, she signed with Universal Music Group’s imprint Republic Records. In her announcement, she cited owning her master recordings and “one condition that meant more to me than any other deal point.” She negotiated so that all other artists on the label would be paid should the company sell its Spotify shares. Swift has also started to work with smaller collaborators. This era has included hiring Valheria Rocha, an up-and-coming Columbian visual artist, to photograph all the images for the Lover album and co-directing her two most recent music videos with Drew Kirsch, who only directed small-time, indie music videos beforehand.

The cruel irony is that Swift lost the rights to most of her own music, having not been protected well enough as a teenager.

To understand the person and artist that Swift is now requires understanding 2016 as a life-changing year for her. That was the year where she experienced bullying on an international scale and then disappeared from public life for months, leaving most of her fans worried. The trauma she experienced, with the subsequent fallout on her art, her personal life, and her politics, and its relationship to her master recordings will be spotlighted in separate articles. The topics are too complex to be sufficiently covered in one piece, but they must be mentioned here for context.

That year saw the resurfacing of the Kanye West debacle. Most people know the general story, but most people have the details wrong, if they know the story at all. Early that year, West released his song ‘Famous’, rapping, “I feel like me and Taylor might still have sex/Why? I made that b*tch famous (Goddamn)/I made that bitch famous.” In her original statement, she acknowledged him contacting her for permission, making it clear he never played her the full verse. What would have been a joke between friends instead became a misogynistic statement, West rewriting her narrative of hard work and self-determination, as he implied that she owed him for her career. His misogyny is reinforced by a leaked demo in which he actually says that Swift “still owe[s] [him] sex”, and when he repeats that verse, he swaps her for Amber Rose instead, a model and ex-partner he slutshamed the year before. Swift and Rose were interchangeable for him, dolls for him to use as he saw fit, which he visualized months later.

In July 2016, he released the ‘Famous’ mv, depicting several major celebrities in bed together. West used lifelike, poseable wax models of the celebrities’ nude bodies, and conveniently the women were the least covered. The sexual violation was exacerbated by having all the figures appear to be unconscious, with rapist Bill Cosby in attendance and with accused-rapist and known batterer Chris Brown beside his former partner, Rihanna. Though Swift’s unconsenting appearance generated the most buzz, West sexually harassed several high-profile women, including Rose. The video constitutes ‘revenge porn’, the “artistic” version of deep fake nudes that any techbro could manufacture with the right software. Kim Kardashian, his wife and social media savant, then called Swift a “snake” on Twitter and implicitly directed her followers to bully Swift. The whole debacle inspired the hashtag #TaylorSwiftIsOverParty and a mural celebrating her “death”, distracting the public from the music video. For months, the snake emoji flooded Swift’s Instagram comments.

After three years of avoiding interviews for her mental health, Swift has finally opened up publically about 2016’s effects on her psyche. Cancel culture is toxic and often traumatic for the target, and reputation explored that devastation and social isolation through the lens of redemptive love, Swift wrapping herself in snake imagery for protection and empowerment. She shed that scaly armor with Lover, embracing butterflies and rainbows. But near the three-year anniversary of her disgracing, her demons resurfaced.

West had been managed by Scooter Braun, a manager with a reputation for allegedly mistreating his clients. Not only had Braun been involved with creating the ‘Famous’ music video, he bullied Swift on social media, with the implication that other negative interactions happened in private. On June 30th, the news broke that Scott Borchetta sold Big Machine to Braun, and so the master recording rights of Swift’s first six albums went to him. That afternoon Swift posted a long, righteously indignant letter to her Tumblr, calling out Borchetta for his manipulations and refusal to even offer her the chance to buy her masters, who instead offered only a contract that amounted to indentured servitude. She also called out Braun for his abuse, writing, “[M]y musical legacy is about to lie in the hands of someone who tried to dismantle it.” Disgustingly, that same day Braun had reposted a friend’s InstaStory about “buying Taylor Swift”, revealing his intentions. He also owns Swift’s music videos from her first six albums, further tainting her legacy.

Whether for research or for pleasure, I cannot watch one of her past music videos without a twinge of guilt. Braun financed the deal with cash from the Carlyle Group, a financial equity firm with investments in his company, and thus he connected Swift’s work to blood. It is an open secret that the Carlyle Group has ties to the Yemeni genocide through its connections to Wesco and BAE, who manufactures weapons for Saudi Arabia. And through the Kushner family, Braun and the Carlyle Group both have ties to the White House, whose chief Swift openly despises and denounces. Swift created a petition for the Equality Act this summer, and though several senators signed it, Trump only responded when she called him out on live television. And he responded in less than twenty-four hours too, restraining himself in an uncharacteristic move.

Conclusion:

While doing research for this piece, I discovered a video taken at the concert where Swift won Video of the Year for ‘Mine’. She had been touring for Speak Now, an album about proclaiming truths — such as calling out an older partner for psychological abuse. Watching the linked video above in 2019 is surreal for me, culturally and personally. Back then, musician Kid Rock had read the card, and before announcing Swift as the award recipient said to himself, “No way, man. Unbelievable.” Now two months ago, Trump-supporting Kid Rock blasted Swift for her Democratic views, using sexual language to denigrate her on Twitter. He clearly never respected her or her artistry.

That June 2011, I was also days away from my birthday, which my father proceeded to ruin with his arrival and his inevitable temper tantrum. It was a difficult year, in hindsight, and one that quietly unraveled me, the empowerment I had gained from the previous year of poetry-writing squashed. And in hindsight, that previous year — summer to summer — I had been memorizing the lyrics to Speak Now. For its refrain, ‘Mine’ includes the brilliant, subtly-tossed-off line, “You made a rebel of a careless man’s careful daughter.”

That birthday was the first time I can ever recall speaking up to my father.

And Taylor Swift is still that rebellious daughter too, still using her art to fight against the traumas and restrictions forced on her by careless patriarchal figures. She has already announced that she intends to rerecord her old songs next year, thus tanking the original masters’ value and reclaiming her work (t. 1:47-2:45). Directing music videos is simply another way for her to reassert ownership of her experiences, especially as she grows in understanding of the social issues that attempt to strip her of her narrative.

I can’t wait to see where she turns the camera next.